I wrote a high school junior class paper on Absalom, Absalom!, and one day I pointed out to the teacher the passage describing Charles Bon lounging in an effeminate silk robe before the cloddish Henry Sutpen. “Does this mean they were homosexuals?” I asked. She replied that Mr. Faulkner “would never write about something like that.” Years later, as a more literate scholar, I found that William Faulkner did indeed write about “things like that”; he wrote about humanity from every angle, including sexuality and homosexuality. Furthermore, I found my assessment of Charles Bon and Henry Sutpen’s relationship supported by others.

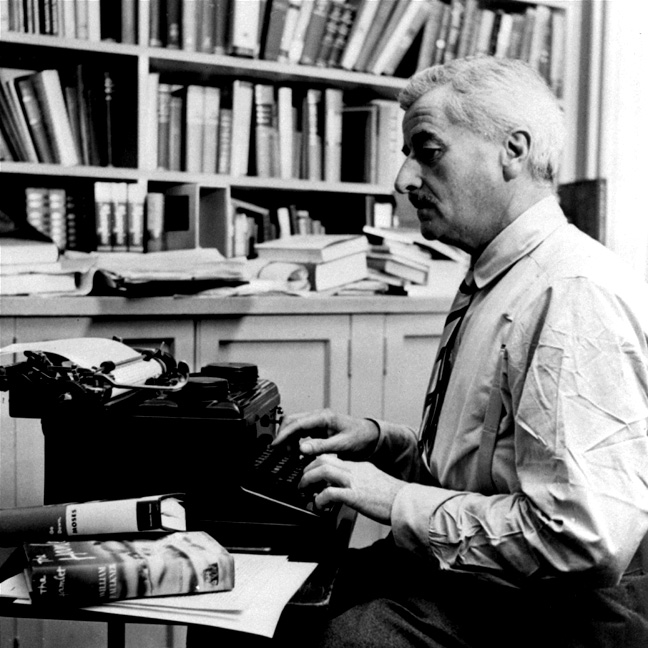

Between 1929 and 1939, Faulkner puslished The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Sanctuary, Light in August, and Absalom, Absalom! as well as dozens of short stories. These works have been thoroughly studied and analyzed, and it’s not surprising that scholars and critics have identified homosexual themes in them. Absalom, Absalom! has been the focus of much interest in homosexual matters, and as early as 1955, Ilse Dusoir Lind commented upon the “affection, mildly homosexual in basis” between Shreve and Quentin.

The first essay devoted to the question of homosexuality in Faulkner’s works was published by Don Merrick Liles in 1983. Absalom, Absalom! and “A Rose for Emily” spurred discussion about homosexuality in Faulkner’s works. The 1980s saw Queer Theory evolve from the increasing visibility of sexual minorities. These critical analyses resulted in a multiplicity of approaches that in turn became dialogues about homosexuality in the Faulkner canon.

These exchanges allow us to see Faulkner’s work differently and over time come to new understandings. With Gay Faulkner: Uncovering a Homosexual Presence in Yoknapatawpha and Beyond, Phillip Gordon broadens our concepts of Faulkner and his works by examining his immersion in gay subcultures throughout his life, especially during the 1920s, and his strong and meaningful relationships with specific gay men, particularly his lifelong friend and sometime editor Ben Wasson. Gordon’s study focuses on male homosexuality simply because that is the most revealing perspective. He also concentrates his study on As I Lay Dying and the Snopes trilogy—with particular emphasis on Darl Bundren and V.K. Ratliff—rather than the major novels of the 1930s in order “to turn a light on other works to bring into focus themes that have not yet been deeply explored.”

Gordon states flatly that the question at the heart of his study is not if Faulkner was gay, but, “Is there a gay Faulkner?” Gordon seeks to reveal a gay presence not only in Faulkner’s work, but also in his life as well, establishing Faulkner’s awareness of homosexuality and homosexuals, and his acceptance and participation in gay culture. Gay Faulkner is a solid academic work; the notes are as absorbing as the text, and the bibliography constitutes a summation of Queer Faulkner studies. Gordon also offers insight, information, and even entertainment for the general reader.

Gordon’s documentation of Faulkner’s stay in New Orleans explores the bohemian atmosphere as well as the writers’ community of the Vieux Carré. Central to this section of the book is Gordon’s account of Faulkner’s relationship with his longtime friend and roommate, the gay artist William Spratling, including an intriguing account of a trip to Italy with Spratling, a journey that resulted in Faulkner’s most openly gay story, “A Divorce in Naples.” This period of Faulkner’s life, as well as the literary and artistic scene in the city at the time, is the subject of an essay by Gary Richards, “The Artful and Crafty Ones of the French Quarter: Male Homosexuality and Faulkner’s Early Prose Writings.” According to Richards, Spratling, not the literary lion Sherwood Anderson, stood at the center of the New Orleans artists and writers. He also points out that Faulkner’s early sketches for the Times-Picayune and the literary magazine, Double Dealer, as well as some of the characters and scenes in Mosquitoes (1927), are strongly homoerotic. Richards’s paper was presented at the 34th Faulkner Conference in 2007; Annette Trafzer states that conference’s subject, “Faulkner’s Sexualities,” is an “intentionally ambiguous” subject that “blurs the line between the author’s body and the body of his work .…” (Trefzer). This conference as well as “Faulkner and Women” (1985) and “Faulkner and Gender” (1994), featured other studies on Faulkner and homosexuality.

With Ben Wasson and the New Orleans-born gay writer, Lyle Saxon in New York City after the publication of Sanctuary (1931), Faulkner interacted with the Algonquin Round Table and met Alexander Woollcott. Faulkner toured Harlem’s gay clubs and cabarets with Carl Van Vetchen, where he attended a show by the famous drag “king” Gladys Bentley. This encounter was recounted by Wasson in the Blotner Papers at Southeastern Missouri State University, a rich source for scholarship that Gordon calls “fascinating, complex, and, for lack of a better word, beautiful.” Despite his earlier disclaimer concerning Faulkner’s personal proclivities, Gordon also avers that “there is evidence in the Blotner papers that suggest our understanding of Faulkner’s sexuality might not be what we have generally assumed.”

Gordon frames Faulkner within the literary milieu of early 20th century Mississippi–by any standards a cutting edge of the Southern Renaissance in American literature–and includes several prominent gay writers. The queer planter, poet, and memoirist William Alexander Percy of Greenville nurtured a clutch of writers, including Hodding Carter, Walker Percy, Shelby Foote, and Wasson. Gordon also illuminates Oxford’s fascinating and cosmopolitan Stark Young as well as the undeservedly obscure poet and scholar Hubert Creekmore of Water Valley.

Gordon and other queer critics focus on the meaning and nuances of a text, and amplify its implications. Some readers may think Gordon is reaching to make a point, but in the end, the words and their meanings are there for any to understand. Gay Faulkner has a great deal to recommend it; it’s interesting, educational, and entertaining. The book is also an excellent introduction to current and ongoing studies that seek to explore new avenues in Faulkner’s work.