Frank N. Meyer’s Lemon

In August, 1905 a Dutch immigrant, horticulturalist and fitness buff became the first plant explorer hired by the USDA’s newly-created Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction to travel the globe in search of plants useful for American agriculture. The first expedition (he undertook three others through 1918) through China, Manchuria and Korea in 1905 was daunting, to say the least, but Meyer was an enthusiast if not to say fanatic, and the constant travel on foot, the weather, the tumultuous politics and the Spartan living conditions were simply taken in stride.

In the Far East Meyer discovered the eponymous plant now most widely recognized by the general public (horticulturalists are also familiar with Meyer zoysia grass). Though Meyer failed to take note of its origin, he probably purchased the ornamental lemon plant from a nursery in Fentai near Peking. Meyer lemon (Citrus x limona ‘Meyer’ or citrus x meyeri) is most likely a hybrid between Citrus limon, the true lemon, and C. reticulate, the mandarin orange. While the Meyer lemon is larger, juicier and more cold tolerant than true lemons, it doesn’t ship well and has never been widely adopted by the citrus industry. In time, it has become successful in limited local marketing and has become a gourmet selection for any number of culinary uses.

Louisiana Satsumas

Juke Joint Tamales

Jefferson House

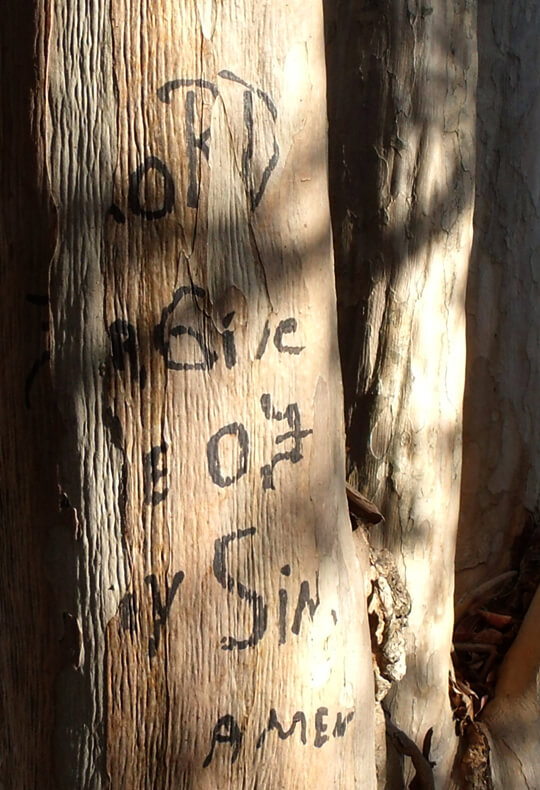

Lord Forgive Me

Parchman: A Review

Documentary photography has been an instrument for social reform since Jacob Riis, who focused the nation’s eyes on the grinding poverty of New York City slums in How the Other Half Lives (1880), inspiring the work of photographers who seek to depict history as well as comment on society. A branch of this genre, prison photography, is by nature dramatic and controversial, focusing on the human condition in confinement (at times awaiting execution) and though their ability to convey the reality of prison as opposed to the projected feelings of the viewer is dubious, the images are inevitably stark and gritty, grim and sullen.

Taking photos of Parchman Prison is like shooting fish in a barrel; it’s a given that the results will be iconic on a documentary level. While it’s arguable that the cruelties and injustices at Parchman are no more heinous than in any other penal environment, this is after all Mississippi’s state prison and carries a particular notoriety for that singular reason. But with Rushing’s Parchman what we have is a failure to communicate; the photos are technically precise, yet without resonance, more substance than style and not edited to bring emotion. The lack of angles, of effective use of light, shadows and contrast is evident; often the quality is purely that of straight-on recording, which in most cases is lifeless and banal, with no finesse and less feeling. The inclusion of text from the subjects (albeit in the form of images) undermines an emphasis on the photographs themselves, leaving us with a definitive visual record of Parchman in the 1990s, which is nothing to deride in terms of an historical document, providing an appropriate companion volume to two significant books about Parchman that appeared in the 90s, Taylor’s Down on Parchman Farm (1993) and Oshinsky’s Worse Than Slavery (1996), but nothing to acclaim in terms of art.

This is University Press of Mississippi’s second foray into the field of prison photography; in 1997 it published Ken Light’s Texas Death Row, which followed on the heels of Light’s Delta Time (Smithsonian Institution Press; 1995). Yet even given the lack of effectiveness in the photographs, it’s reassuring that University Press of Mississippi is still on top of their game; though it has at times dropped the editorial ball, when it comes to putting together a quality product, University Press can and has given Rushing’s photos good framing.