Serving People

Anyone who prides themselves on their patience and understanding should wait tables for a week or so to find out just how patient and understanding they really are. Many people are notoriously insensitive to workers in the food service industry; just ask any waitperson, bartender or cook. Any given one of them doubtless has several stories to tell of rude and insensitive if not to say vulgar treatment at the hands of a patron. The business of food and drink is a service industry, and it’s no coincidence that the word service comes from the Latin root servus, meaning slave. The food industry trains people to be servile, to cater to customers (and management) in an overtly deferential way because so much of a restaurant’s livelihood depends on steady patronage. I’m not suggesting that anybody who works in the business is at the beck and call of every s.o.b. with enough money to buy a hamburger, but some people certainly seem to think so.

In her autobiography, My Life as a Restaurant, Alice Brock, owner of Alice’s Restaurant, describes the situation well and offers a very human response:

I am often accused of being rude to customers. Well, it’s true, I am as rude as they are, only they don’t always realize their behavior is inhuman: after all, I am in a restaurant and THEY are hungry, THEY drove all the way from Florida, THEY just want a sandwich, THEY just want to see Alice, THEY just want to look around, and take a picture, get an autograph, use the bathroom, introduce me to their dog, who is named Alice, have a cup of coffee, SPEAK TO THE OWNER…because this food-covered lady in work boots, who is so rude, can’t possibly be the OWNER. I guess I have a temper…good! I won’t stand for being treated like a piece of public property or a freak and I will never allow a customer to get away with giving an employee a hard time. The customer is NOT always right. Being a “service industry” makes people think we are just computerized slaves.

One of the high-lights of an evening is to hear of a customer bringing a waitress to tears…I rush out to the dining room, pull their plates off the table and point to the door: “OUT…OUT…GET OUT AND LEARN SOME MANNERS!” To try to please the “difficult” customer at the expense of my fellow workers is ridiculous. Some people just have an attitude. They upset the waiter or waitress, who in turn upsets me, who in turn upsets the whole evening. It’s not worth it to try to please or placate these bitter, unhappy people, better to put them out at the first sign of trouble. This is something I have to be there to do…it’s hard to tell or expect someone else to do it. Sometimes I’m wrong, or the waitress is wrong, but better to lose a customer than a co-worker. (p.119)

Ms. Brock is a notable exception, I might add, since most managerial-type people treat their waitstaff as expendable. And, to be fair, most people who eat out frequently learn how to deal courteously with waiters, but I’ll be the first to admit that it is a learning process, not an instinct. Nowadays, dining out is almost always coupled with another experience (a movie, a play or some other sort of public entertainment) but at one time dining out itself was often taken as a singular occasion to be enjoyed on its own merits rather than as an appendage to another event. This happy time was when restaurants were successful not merely on the basis of turnover, but more on the quality of the foods they offered, the comfortable atmosphere they maintained and the genial clientele they accommodated. Great care was taken not only with the menu, which usually involved many courses designed to fit the season as well as the particular talents of the cooks and the general style of the restaurant itself, but also with the presentation, the service, the table, seating, lighting and other elements of atmosphere. Such staging demanded a great deal of planning as well as much care in the execution.

I have seen some degree of return to this tradition, but it is still rare to find a restaurant that does not cater to some abominable god of expediency. I’ve often encountered difficulty when dining out and trying to take my time between one course and the next with a pause to have a bit of beverage and conversation because waitpersons tend to interrupt with an insistent, “Are you alright?” as if to say that by not yelling at them for not bringing the food immediately that they were falling down on their job. The reason for this is that waiters are programmed to turn over tables as quickly as possible and since most patrons have had the “20% tip” rule-of-thumb drummed into their heads, waiters are eager to get the ten or twenty buck tip and get you out in order to get the next ten or twenty bucks. (Me, I tip as well as I can; just want you all to know that.)

To learn how to wait tables efficiently and unobtrusively is an art; I’ve known some champion waiters from both sides of the kitchen doors, and I’ve been subject to the attentions of some world-class bartenders (be nice, people). Yet some customers, out of ignorance or stupidity, will exhaust and demean a good waiter, detracting not only from their own enjoyment of a meal but also from that of others. Bartenders, on the other hand, just will not put up with a bunch of bullshit; trust me, I know. Perhaps what I’m describing is simply an example of what is being called a decline in civility, but, as Alice says, “Some people just have an attitude,” and in my book as well as hers, such people simply require an adjustment. This, you understand, takes patience and understanding. To a point.

Gingerbread Home

Over time many dishes have been needlessly–and recklessly–consigned to specific holidays. How often do you roast a turkey, stuff eggs, or make a fruitcake? What’s sad and paradoxical about this occasional consignment is that many dishes we prepare only for the holidays are those that bring us the most comfort, that make us feel most at home and closest to the heart of our lives.

Gingerbread is an extreme example of this culinary exile, particularly because when gingerbread is prepared even for the holidays it’s most often make into cookies. Instead, let’s make loaves any day of the year, any time of the day. Many recipes employ equal measures of cinnamon, cloves, and allspice as well as ginger–almost as an afterthought–but ginger should shine.

Cream a stick of unsalted butter with a half cup of light brown sugar, beat until fluffy, and mix well with two eggs and a half cup of sorghum molasses. Mix one and a half cups of flour with a half teaspoon of baking soda, a teaspoon each of cinnamon, ground cloves, and allspice along with a heaping tablespoon of ground ginger. Add two teaspoons vanilla and a half cup buttermilk. Pour batter into a buttered loaf pan and bake at 350 for about an hour. If you have the willpower, cool before slicing. I never do.

Raymond Courthouse

Paleolithic Pleasures

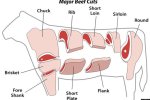

Ever since the Fall, no food has sparked more controversy than meat: some eschew it and even more restrict it, but meat, for most people, is what’s for dinner. By meat we mean red meat. The USDA considers all meat from livestock red because they contain more myoglobin (aka “red stuff”) than poultry or fish. For most people, this means beef or pork (yes, “the other white meat” is red), though sheep and goat as well game such as venison—and for that matter, whale—fall into the same category. Beef and pork in their various incarnations constitute a significant portion of our diets. An average American consumes 67 lbs. of beef and 51 lbs. of pork annually, most of it at home, meaning that the majority of people buy meat raw and cook it themselves.

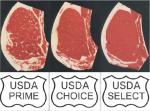

“I have a few pieces of choice rib eye that I’ve prepared in a display tray with a prime rib eye to educate people in the difference between the marbling. Less than 3% of all beef in the United States rates a prime grading.” Paul says that supermarket chains are not an ideal place to shop for the best cuts of meat. “Most supermarkets aren’t even cutting their own products locally. Kroger, for instance, has most of their meats cut in Cincinnati and then shipped out.” Paul explains that their reasoning behind this is the liability factor in using saws and other cutting instruments in their stores.

The practice of aging beef is another factor contributing to flavor and tenderness. “All of my prime beef is wet aged, vacuum-sealed in a package in its natural juices. Wet packaged beef will have a stamp that tells me how many days it has been aging since the slaughter. Dry aging is a whole different process,” Paul says. ”Humidity and temperature are keys. Every product is out of the bag with no liquid around it, and the enzymes are breaking down the meat, making for a really rich flavor.” Paul explains that quality pork is the product of a nationwide program in which farmers are raising heirloom breeds of swine without using hormones or strong antibiotics. Sometimes referred to as heirloom or heritage breeds, examples in the marketplace today include Berkshire (also known as Kurobuta, meaning “black pig”), Duroc, and Tamworth “There’s an amazing difference in the taste and tenderness between this pork and what you’d find in most supermarkets,” Paul says. .

Then there are marinades and dry rubs. “Marinades flavor and tenderize meat,” Dan says. “A marinade normally incorporates an acid, which is a natural tenderizer, whether the acid is wine or vinegar, lemon juice or lime juice. For a tougher piece of meat you’d want the marinade to penetrate more. But if you’re cooking a rare piece of meat, and the marinade penetrates too far, the acid will cook the meat, and it will soak up the marinade like a sponge, giving the meat a different texture. Dry rubs are another excellent way to flavor meat,” Dan says. “You always want salt and pepper; something with a little heat, like different types of peppers, then some dried herbs like rosemary, oregano or fennel as well as powdered onion, garlic and paprika.” Dan recommends that any cut of meat, once cooked, should rest for a few minutes before carving or cutting.

Pork Saltimbocca

12 oz. pork tenderloin, sliced into 6 medallions and pounded thinly

6 thin slices prosciutto

6 large fresh sage leaves

Dredge pork in all-purpose flour seasoned with salt and black pepper. Arrange 1 prosciutto slice over pork. Top with 1 sage leaf and spear with a wooden pick. Heat about 1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil in a sauté pan, add pork and brown lightly. Remove pork; add about a tablespoon of finely chopped shallots and a teaspoon of garlic. Add about 1/4 cup each white wine and chicken stock to pan, cook until reduced by about half, finish with about a tablespoon unsalted butter. Arrange pork on a warm plate and drizzle with pan juices. Serve immediately.

Portland Backstreet

Syracuse Sunset

Tio Jesé’s Pickled Avocado

Use firm avocados. Peel and slice as you like, then soak in a bath of cold salted water and lime juice for about an hour. This step draws some of the oil from the avocado, making it more receptive to the pickling liquid (makes them prettier, too). Drain, dust generously with salt and red pepper flakes, and pack into jars. Fill jars with white vinegar, then pour vinegar from jars into a saucepan. For each pint of liquid, add the juice of half a lime, a teaspoon each of whole black peppers, yellow mustard seeds, and diced cilantro.

Priapian Hymn #57

Cupped, cradled, ADORED—everything in one stride.

There, where you crease your form, a presence

Coiled, cuffed, MOORED—something of space, a pride

Of lions, three in hand–the rope, eternity, ESSENCE.

How once I BURNED to find, to feel, to hold,

To KNOW carnality—rampant, quaking lust—

But what where who ? No boldness

Came to free, to see the fire was JUST.

Now throbbing in my THROAT I thrust in need

My tongue, my teasing teeth seek musky cream.

PRIAPUS MAGNUS! Bloat my mouth with satyr’s seed,

Foam my beard, a faun with me to dream.

So now the What the Who the WHY have fled,

Make MY tongue the temple for your head.