Beauty

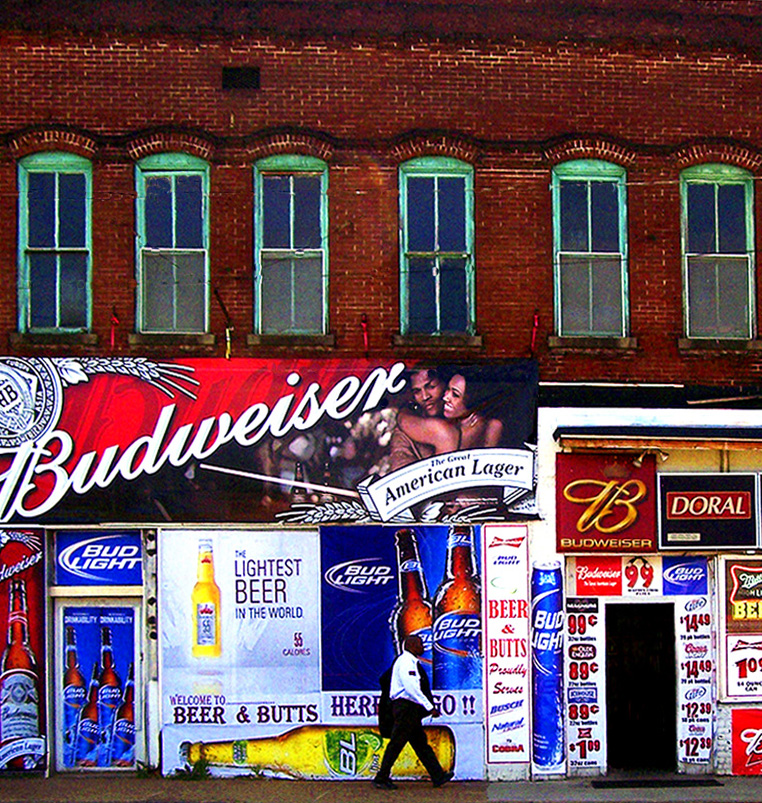

Lewis Dairy Bar

Beatty Street Grocery’s Hungry Man Hog

Purple Gladiolus

Jake’s Meat Loaf

Season 2 lbs. 90/10 ground beef with black pepper, dark paprika, two cloves minced garlic, a sprinkling of salt and mix well with one white onion finely minced and sauteed in light oil until cooked, a cup of panko bread crumbs and two whole eggs. Shape and bake in a medium hot oven (350) for an hour and a quarter.