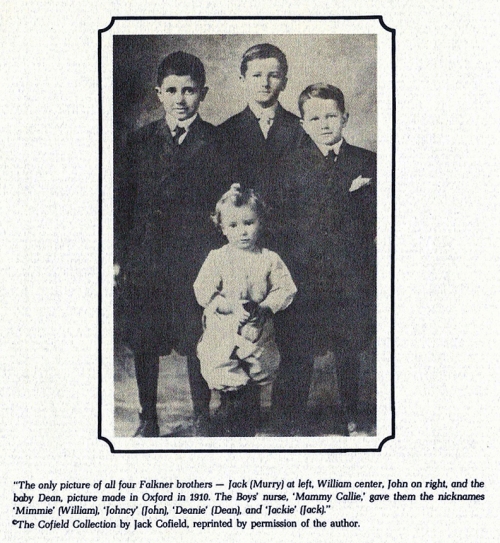

This image from A Cook’s Tour of Mississippi (The Clarion-Ledger: 1980) accompanied an article by Dean Faulkner Wells, “The biscuits Nannie and Callie baked for the boys.” Into 1 qt. sifted flour work well 1 tblespn each lard, butter and teaspn salt. After well worked moisten with 1/2 pt. (sweet) milk and make stiff dough. Beat by hand. Bake quickly.

Confessions of an Urban Planter

In my hometown of Bruce, Mississippi, Mr. Buddy Massey grew cotton every year in his circular drive at the Shell station on the corner of Hwys. 9 and 32. So when I hacked out a small garden on what was once a barren, sun-scorched verge in Jackson, Mississippi, I figured if Buddy could grow cotton on the street, I could, too.

This project encountered obstacles right off the bat. First and perhaps foremost I discovered you need permission to grow cotton in Mississippi; the shadow of the boll weevil still looms over the Cotton Kingdom, and the Mississippi Code states specifically that “Every person growing cotton in this state shall furnish to the commissioner and the corporation on forms supplied by the commissioner such information as the commissioner may require concerning the size and location of all commercial cotton fields and of noncommercial plantings of cotton grown as an ornamental plant or for any other purposes.” Having found that out, I knew having the Mississippi Department of Agriculture in a building a mile and a half away magnified my chances of getting busted for cotton, and though the novelty of being hauled to court for growing cotton in Mississippi did have some appeal, I called the Commission out of a hard-learned habit of caution when it came to flirting with the law. The MDA folks directed me to a scholar at Mississippi State University who assured me that such a small “field” as mine wasn’t an agricultural time bomb. Naturally, I considered his opinion testament; if he’d been from Ole Miss, I’d called him a lying son-of-a-bitch.

Second, getting the seed; cotton seed, because of the restrictions, is not something you find in a yard and garden emporium. They seem to be sold not by the bushel, nor even the pound, but by the seed; the individual seed, mind you. At a loss, I issued an appeal on the local social networks for help, which came forthwith, netting me not only enough seeds for my modest enterprise, but enough to plant a city block. For some time, I considered the novelty of becoming a Jesse Cottonseed, spreading the wealth of white gold across Jackson’s cityscape, but in the end, I decided that I would never live down the shame of being the man who reintroduced the boll weevil to Mississippi. I’d probably be pilloried, then burned at the stake, at the very least tarred and feathered and exiled to Arizona.

Third, waiting for it to get warm; we had a typical winter, but a cool spring. The first batch, planted in outside seed flats on April Fool’s Day of course failed, so I decided to sit on my haunches and seed while my part of the earth tilted more towards Sol. The first week of May, I heard that cotton planting had begun in the Delta. With two beds ready, I sowed my cotton by hand, which was a less-than-mystical experience than I had anticipated, but shouldn’t have, since cotton itself is a plant, and what aura it has is what we have given it; besides, it was the seeds themselves which no doubt found an exhilaration in being thrust into warm, moist soil after such a wait.

Of the four beds planned, the ones on the east and west were planted on May 5. Since my appeal for seeds had netted no less than three copious batches (in different colors, I might add, blue, brown and purple due to the fungicides which coated them), they were mixed together in a batch and sown, some in short rows, others in small hills. Predictably, once the seed was planted, the rains ceased, and watering began, not just for the cotton, but for the other seeds and seedlings already in place; their roots, once established, would sustain them in months to come, but the roots themselves had to be encouraged.

For whatever reason, the cotton seeds proved fickle. To make a series of mini-rows, a total of perhaps fifty were planted each round, each planting a mixture of the three seed types, those with a purple coating proving the most viable. Rainy weather in mid-May helped the second set, and before long the rows (as such) began to take shape, not only in lines but in triangles and circles. Only the closest of seedlings needed thinning. In Delta fields, such fussy tending is not necessary, but being fractional this acreage needed more attention to crowding; in this instance, optimal outcome involving big, pretty plants that would bloom and boll. A rainy May helped; the cotyledons and stems grew big and fat.

By the end of the month, some seedlings had preliminary leaves, and I decided to wait on thinning. On the one hand, I wanted the best plants possible, but then I’ve seen cotton growing close together, and in the best situation of open field and plentiful rain, all the plants were tall, leafy and in flower. Somehow back in the back of my mind I kept trying to imagine what kind of machine planted cotton, and I couldn’t envision it being less haphazard than me. I tried to imagine how cotton must have looked in its primeval state in Tehuacán, predictably failed but persisted. While many scoffed at my crop, growing cotton had become more than an endeavor; it had become a responsibility, and my care paid off. By the first week in June, the cotton was about six inches tall and the cotyledons were being replaced by true leaves. Though my beds received only five hours of direct sun a day, the stems were strong and red, so I decided thinning needn’t be that drastic, since cotton in row crops grows much closer together.

In the Deep South, we have nothing resembling the graduated springs and falls of more northerly latitudes, and while our winters are predictably brief and comparatively mild, summer has such a duration that it can be divided into three parts: new summer, high summer, and far summer. The summer solstice marks the beginning of the high summer, when daytime temperatures are in the nineties and seventies at night. By that time, the cotton was a foot high; it was lay-by time. The cotton grew taller, I took no notice of what was happening beneath the canopy of leaves and found myself surprised in early July by the first blossom, a pale crimped envelope of crepe protruding from a frilly green box.

Again, I’d been anticipating a transcendental moment for the occasion, but my reaction was more composed of surprise and curiosity, which for all I know may well be the essential elements of a transcendent experience. I lack a frame of reference. Pale at first, the petals of the blossoms turned a rich purple before dropping. My neighbor John Lewis said that in Leflore County they have a saying: “First day white, second day red, third day from my birth I’m dead!” When the blooms had fallen, they left a tight, blocky wad of green still enclosed in a feathery case. On this bud empires had grown and tumbled, but other work distracted me.

The first boll opened the last week of August. I saw it under the light of a nearly-full moon, a low, white symmetrical glow against shadowed green. Again, no thunder and lightning came, but though a friend in Arcola had sent me photos of a local field crop waist-high and plush with open bolls along with disparaging comments about my “scrappy-ass Jackson ‘plantation wanna-be’ cotton”, I was proud of my little fraction of an acre. Sure, I was a half-assed farmer in the middle of Mississippi’s capital city, but I was making an effort, and I was, after all, making a crop, one that fit well with my modest and unpretentious character as an urban planter. It’d never make anything like a bale, but I’d have cotton to harvest.

To my astonishment, the opening cotton proved unrecognizable to many if not most of my neighbors. On many occasions I found myself faced with the question, “What is that?” as someone pointed to the whitening bolls. “Cotton,” I’d say, and they would either slap their foreheads or form a silent “o” with their lips. These reactions became a general rule of thumb for determining who of my neighbors were from where, and I’d always ask, but then I found that people from North Carolina and Tennessee didn’t recognize the plant, either. Most of them didn’t know an oak from an elm, either, but I’d cherished the notion that most Southerners would recognize the most iconic crop of their homeland out of repetition if nothing else. Perhaps the image of a cotton boll itself has become so divergent from reality that its actuality has become inconceivable to anyone save those who plant the seed.

As the weeks drew on, every surface of the cotton, leaves, stems, even the ripening bolls, became scorched, ruddy and freckled beneath the unrelenting sun. While the cotton was reddening, the trees were yellowing, becoming sallow, assuming that peculiar jaundice I found familiar from past Septembers. The air itself became hazy because what brief winds we had were picking up the dusty earth and passing it around as they do with pine pollen in June. Everything had a sense of resignation about it, even the light, which seemed suspended in ether, hung between a pale blue sky and a dark dun earth. The world was a sepia silhouette, creaking with crickets, and the leaves were falling. Blistered by the sun and exhausted from their efforts to make seed, the cotton plants drooped under the weight of the swelling bolls, which were opening ever-so-slowly.

October became a coda; the heat and the light had waned, and the year itself was coming to a close. I picked my cotton, ending up with no more than a grocery sack, but a better harvest came from the very reality of growing cotton on the side of a street in Jackson, Mississippi.

The Great Spinach Myth

The facts I use to frame my worldview are steadily becoming ash in the burning light of truth. The process seems interminable; just today, I found out about spinach, and the earth quaked a bit.

Whenever Popeye the Sailor Man needs super strength, he squeezes open a can of spinach, pours it down his throat, and turns into a pipe-smoking dynamo. And it isn’t always Popeye who eats the spinach. In one toon, he forces the spinach down Bluto’s throat so Bluto will work him over, and he’ll get sympathy from that slivery wench, Olive Oyl. And in one cartoon, when a Mae West-like competitor is flirting with Popeye, Olive gets fed up, downs some spinach, and beats the shit out of that hussy. Popeye’s creator, Elzie Crisler Segar, gave his sailor the ability to power up by eating a can of spinach because it was widely known that spinach was a superfood that was packed with iron.

The truth is, spinach has no more iron than any other green vegetable, and the iron it does contain isn’t easily absorbed by our bodies. Spinach’s reputation as a super-source of iron began with a mathematical error. Back in 1870, Erich von Wolf, a German chemist, examined the amount of iron within spinach, among many other green vegetables. In recording his findings, von Wolf accidentally misplaced a decimal point when transcribing data from his notebook, changing the iron content in spinach by an order of magnitude. Once Wolf’s findings were published, spinach’s nutritional value became legendary. This error was eventually corrected in 1937, when someone rechecked the numbers. Spinach actually only 3.5 milligrams of iron in a 100-gram serving, but the accepted fact became 35 milligrams. (The miscalculation was due to a measurement error instead of a slipped decimal, but whatever.) If Wolf’s calculations had been correct each 100-gram serving would be like eating a small piece of a paper clip.

The myth became so widespread that the British Medical Journal published an article outlining the laboratory error in 1981, but spinach’s reputation as a powerful iron supplement has only recently diminished. I’d like to think that’s because of kale instead of nobody watching Popeye anymore.