This is an excerpt from Bitterweeds: Life with William Faulkner at Rowan Oak, a memoir written by his step-son Malcolm Franklin and published in an exclusive edition by The Society for the Study of Traditional Culture in 1977. Franklin, who became a herpetologist of all things, is himself a capable writer.

One of the most frequent questions that people ask me about Faulkner is about his writing routine and writing habits. Pappy really had no set routine. He worked in an apparently erratic manner. I do know one very important fact. He never carried a notebook or made any notes. He did not at any time carry a pencil or paper. He seemed to work largely from memory and observation.

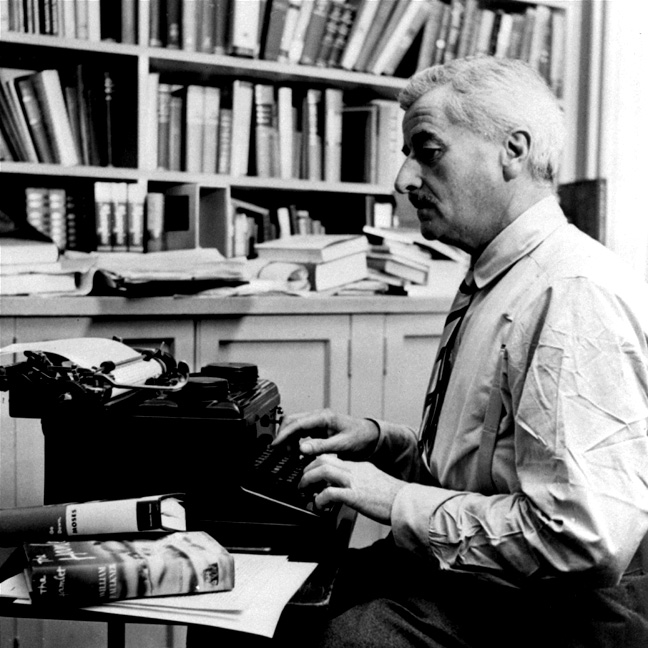

He had a small portable typewriter that was presented to him by an old sailing friend, Jim Devine, whom he had known in New York in the late twenties. To this very day it remains in what is now known as Pappy’s Office at Rowan Oak. I always associate it with Pappy’s noisy periods, the ones that let us all know Pappy was at work. During what we referred to as his silent days, he used pen and ink. On such days you could not be sure whether he was writing or not. It was all very quiet. No telephone, no radio and no doorbell! These were forbidden items. All you could hear were the sounds from the woods beyond the formal gardens and the barnyard. The dogs would bark. A rooster who had lost the time of day might unexpectedly crow. Cows would occasionally let out a low moo reminding those in charge that milking time was near. Otherwise, only silence; for we were too far from the road and out of the way for the sounds of traffic to interfere.

Then there would be the times I would see Pappy walking along the driveway, perhaps headed for a walk down Old Taylor Road, in the direction of Thacker’s Mountain, some six miles away. It was not out of the ordinary for Pappy to cover the distance between Thacker’s Mountain and back in one afternoon. Quite often I would go along, riding the small quarter horse that Pappy had given me, Dan Patch. Pappy, of course, walked through the woods, and by the time I reached Thacker’s Mountain by the road, there would be Pappy sitting on top of one of the large boulders, perfectly still, not saying a word. I would ask, “Pappy, would you like to ride Dan Patch back and let me walk?” “No,” he would always answer, preferring to go through the woods rather than by the road. Upon returning to Rowan Oak he would not say a word. Instead he would go straight to the library, or to his bedroom, where he had a small writing table. And then you would know he was writing. Even in the silence.

Another trait of his which took him outdoors but was still connected with his writing was squirrel hunting. Every fall, on Saturday and Sunday mornings, and often on weekday afternoons, too, Pappy and I would hunt squirrels—always at least one mile from Rowan Oak. The squirrel we were after in particular was the fox squirrel. Unlike the ordinary gray squirrel, who carelessly slits about, the fox squirrel demands great patience from the hunter, for he will sit perched motionless on a limb for long intervals at a time. The hunter must outsit the fox squirrel. If he waits long enough, in absolute silence, the squirrel will show himself in a vulnerable position. It was during these long periods of utter silence that I believe Pappy did a great deal of his thinking about the plots and characters he was writing about. He never said anything about it. However, many times when we arrived back at Rowan Oak he would say to me, “Buddy, would you dress out my squirrels? Or have Broadus dress them out for me?” I would reply, “Certainly, Pappy,” and then he would disappear, and I would hear the typewriter going for the rest of the morning. Other times he would come on back and dress out the squirrels with me.

We would never have more than two or three each at the most. Pappy brought me up never to kill more than we would need. Further, to make our stay in the woods longer and more of a sport, Pappy and I had a pact where we would only shoot for the head. We kept an old tin tobacco box with a slit in the top. Either of us who hit a squirrel anywhere but the head had to put a quarter in the tobacco box. When it was full, we bought a bottle of bourbon with it. Preferably Jack Daniel’s. Despite the fact that there have been many stories told about Faulkner’s drinking habits, including the statement, in many cases, that he was an alcoholic, he was not. It is a fact that he was a hard drinker. But only on occasion. And during a period of twenty-five or more years of close association, I never observed Faulkner’s drinking heavily while he was actively writing.

Faulkner gave a well-deserved reply to columnist Betty Beale of The Washington Star, whose society gossip column was widely read. She asked for the largest number of words he had penned on one day. His answer, printed in the June 14, 1954 column, clearly showed his attitude when he was asked a stupid question He gave an absurd answer: That he had climbed to the crib of the barn one morning with his paper, pencil and a quart of whiskey, and pulled the ladder up behind him; when daylight began to fail, he realized he had torn off five thousand words. In our barn at Rowan Oak there was no crib overhead—only a hay loft with no retractable ladder.

When he had completed a particularly long and involved piece of writing he would take a Sabbatical, indulging heavily in his favorite bourbon. Perhaps it might last a month or six weeks. Quite often the last week of his binge I would spend driving him around Lafayette, Marshall, Yalobusha and Panola Counties. In the summertime we would drive in my jeep. In the wintertime the excursions would take place in a closed car. He would sit there in the front seat, viewing the countryside. But sometimes he would carry on a very animated conversation with me in which he showed his love for and knowledge of that section of North Mississippi. He would point out places he had drawn on for certain incidents in his books or stories. Thus, I know exactly the location of As I Lay Dying, which is southeast of Oxford on the south side of the Yocona River. The location of one of his best stories, “The Hound”, is northeast of Oxford in the Tallahatchie River bottom, in a locality known as Riverside. On one long drive we made together in my jeep, he said, “This is where ‘The Bear’ took place.” We were passing through the old Stone place, between the Sunflower and Tallahatchie Rivers, some seventeen miles southwest of the old river town known as Panola, situated a few miles north of Batesville in Panola County. It was in the late fall, I believe, and we had been hunting at Mr. Bob Carrier’s plantation, where Pappy took Clark Gable to hunt once in the late 1930s.

On our return trip to Rowan Oak that evening, we travelled along an old, dusty road. Cotton stood on either side of the road, but much shorter and scrawnier than that we had passed earlier, around Batesville and Clarksdale in the Delta country. Pappy had noted there that some of the cotton had been picked by hand, some by machine—this was one of the earliest occasions, if not the earliest, that we had seen machine-picked cotton fields. Now from the road we could glimpse the tops of the trees in the river bottom beyond the fields—just a faint outline against the fast fading evening. From Pappy’s silence I realized, as we had rolled along this country road, that he was headed towards his typewriter again, and that soon I would be hearing once more the tap-tap sounds that so often penetrated the quiet darkness of Rowan Oak at odd hours during the night.