If you care about the culinary history of America, then The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region by Marcie Ferris is a necessary addition to your library. The scope of this work, its scholarship and its pervasive voice of authority provide a much-needed center of gravity for the study of Southern foodways as well as a panoramic portrait of the society and culture of the South through the lens of an essential element: food.

In her introduction (following four pages of acknowledgements) Ferris states that The Edible South is an examination of “visceral connections” involving the “realities of fulsomeness and deprivation” and the “resonance of history in food traditions”, and, borrowing Zora Neale Hurston’s reference to food as an eyepiece for the examination of history, an “evocative lens” into the various aspects of Southern culture and society. The text is peppered with phrases such as “culinary exceptionalism”, “cultural conversation”, “historical interaction”, “Jim Crow paternalism” and “racial balkanization”, thoroughly saturated with information (as well as footnotes) and for the most part unrelentingly didactic, an almost incessant record of racism and misogyny, poverty and oppression in one of the most fertile regions of the globe.

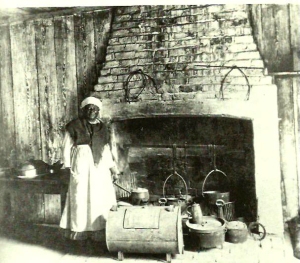

The narrative is occasionally gruesome: the slaughter and cannibalization of a young pregnant bride at Jamestown; the torture of a slave by being suspended with a piece of pork fat over an open flame; and the rats, cats and dogs prepared for the table during the siege of Vicksburg in addition to constant accounts of hunger, malnutrition and want, evocative to be sure, but far more often of the darker aspects of the human condition.

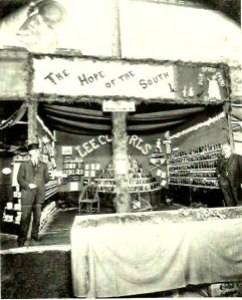

Ferris is vigorous and precise, as befits a writer intending to inform if not to say instruct. While she professes a passion for food, this passion is rarely evident in her prose; instead, it shines forth in her scholarship, which as noted is astoundingly thorough. The key word here is information, and The Edible South is informative on almost every level, but this is a social history (as opposed to political or economic history), focusing on the experiences of everyday people, resulting in “a ‘History from the Bottom Up’ that ultimately engulfed traditional history and, somehow, helped to make a Better World” (Paul E. Johnson). The emphasis is on race relations, gender issues, inequality, education, work and leisure, mobility, social movements and the character and condition of the working class.

While Ferris states her approach is not encyclopedic, her product is undeniably, mind-bogglingly comprehensive. The bibliography is exhaustive, beginning with three and a half pages of primary source materials from archival collections in fifteen cities spanning fourteen states (including Michigan, Massachusetts, Ohio and the District of Columbia), followed by forty pages of secondary sources. Somewhat surprisingly, Ferris mentions Zora Neale Hurston only in connection with the reproduction of her folk tale “Diddy Wah Diddy” (1938) in Mark Kurlansky’s excellent work, The Food of a Younger Land (2010), disregarding her longer non-fiction works. I should hope to find some agreement by noting the glaring omission of Wilbur Cash’s The Mind of the South (1929). While not genre-defining—John Egerton’s Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987) defined the genre—The Edible South is authoritative and comprehensive, an indispensable reference.

The academic institutionalization of Southern food is if nothing else thorough. Southern foodways studies have kept university presses rolling in recent years: Andrew Haley, an assistant professor of American cultural history at the University of Southern Mississippi, was awarded the 2012 James Beard Award in the Reference and Scholarship category for Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920, another product of the University of North Carolina Press; this past October, the University of Georgia Press issued The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South, edited by John T. Edge, Elizabeth S. D. Engelhardt and Ted Ownby; and this August the University Press of Mississippi released Writing in the Kitchen: Essays on Southern Literature and Foodways edited by David A. Davis and Tara Powell with a forward by Jessica B. Harris.

After reading The Edible South, some are likely to be left with the bitter aftertaste of an eviscerated region in an age of information. The apart-ness of the South brought about its distinctive culture, but the old demonic genius loci of Dixie has been exorcised by a new orthodoxy embracing secular capitalization and academic hermeneutics, where icons are relics and texts are subjected to a democratized version of the Scholastic method. A bell jar has descended, but life goes on, people will be people, and while by academic standards Southern culture has become a global phenomenon, for better or worse it remains rooted south of the Mason-Dixon Line, where a pork chop is still more often than not just a pork chop.