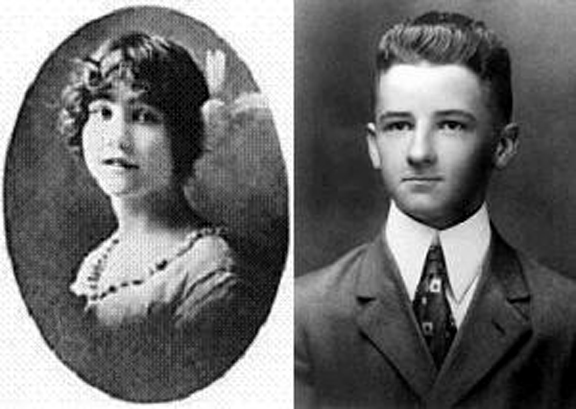

In this foreword to her son Malcolm Franklin’s Bitterweeds: Life with William Faulkner at Rowan Oak, Estelle Oldham (Franklin) Faulkner recounts her life before and wedding to her second husband, written at least five years before the publication of the book in 1977, the year of Franklin’s death.

For those who may be interested in Malcolm’s story of his close association of William Faulkner, I, his mother, feel compelled to write an unsolicited, explanatory forward. My son has written his own preface, as well as the text with follows—I use the word “text” advisedly, because fiction—imagination and literary embellishments—is completely foreign to his factual way of thinking.

Malcolm was born in Shanghai, the son of my first husband, Judge Cornell Franklin. We also had a daughter, Victoria (called Cho-Cho by her Japanese nurse-maid, and eventually by everyone but her father), a few years older than Malcolm. We were living in Hawaii when she was born, and she was still quite a mall child when Judge Franklin decided to move to China and go into the private practice of law in this flourishing international city of the Orient. A few years later Cornell and I agreed on an amicable divorce, and I brought the two children back to Mississippi.

It is not my intention to write a biography, but I feel the necessity of establishing the fact that our divorce did in no way alienate the deep affection of my former husband’s family in Columbus bestowed upon me. Visits by both families between Columbus and Oxford became frequent, mainly, perhaps, on account of the children. The train trip from Oxford to Columbus was particularly irksome—a change, and a long wait in a town called Winona. This is how Judge Franklin’s family met, and got to know, William Faulkner so well, for Bill would often drive us over, and he was very reluctant to forgo their hospitality. Their welcome was all too sincere. “Gran” (Victoria’s and Malcolm’s Franklin-side grandmother) was a charming and admittedly romantic woman, and it was she who approved and applauded my marriage to Bill. She also unhesitatingly upbraided my father for coldly insisting that I’d married a wastrel.

All this brings me to what I’ll wager was the strangest of honeymoons—one even a novelist would hesitate to invent: the groom a bachelor, the bride a divorcee with two children, and all of us having a gay, carefree time in a tumble-down old house on the Gulf of Mexico, with a colored cook loaned to us by my first husband’s mother.

It was late afternoon, the twentieth of June, 1929. My sister, Dorothy, had gone with us to College Hill, a village several miles from Oxford where there was a beautiful old Presbyterian church and an elderly minister whom we all knew, and who gladly performed the simple ceremony. At times I’ve wondered if Dr. Hedleston welcomed us to the church and married us out of pure Godly love and understanding, or was he thumbing his nose at the Pharisaical laws imposed upon divorce by the Episcopal Church? I’ll never know the answer.

Bill and I had talked over our plans for the honey-moon at some length. A friend of his had turned over a big old beach house for our use—unrentable, because at that time Pascagoula wasn’t a fashionable Gulf resort. Victoria was in Columbus with Gan, so Bill insisted that Malcolm be picked up with all our luggage, and dropped in Columbus till we’d gotten settle in our borrowed summer home. How simple it all sounded! I had left a note with Mama about taking Malcolm with us, so I thought that all we had to do was to take Dot home, gather Mac (Malcolm, jly) and the luggage, and take off for Gran’s. She was expecting us.

Mac was still such a baby that I had a nurse for him. Ethel Ruth was a fine playmate, but couldn’t read or write, or even tell the time by a clock with Roman numerals. So when Bill steered the car into our drive way, we found the child dirty, grass-stained and generally unkempt. Bill laughed, thrust Malcolm in the car, stowed our many bags, said good-bye to Dot and headed east toward Columbus.

By then it was late afternoon. We drove as far as Tupelo, and got rooms in the only hotel. I bathed Mac and gave him supper while Bill telephoned Gan that it would be impossible to travel further that night—to expect us for dinner the next day.