Parochialism is endemic in rural America, and though Southerners are of a naturally hospitable nature, they and Mississippians in particular have an acquired sense of xenophobia engendered by their brutal treatment at the hands of outsiders, most especially writers. In the case of Mississippi, perhaps the most stupefying recent example of such mistreatment comes from Bill Bryson, a native Iowan and former chancellor of Durham University, U.K., who recounts his visit to Mississippi in The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America, in which Bryson chronicles a 13,978 mile trip around the United States in the autumn of 1987 and spring 1988. Bryson’s tale of his journey through Mississippi is as full of bile as most American writers who venture south, packed with shopworn stereotypes and clichés, saturated with ridicule and derision. He left Mississippi with impressions of the state that are what we have come to expect of most people who visit with baggage consisting of preconceived prejudices and with no desire to do anything more than capitalize upon the surety that their condescension would be well-received by the world at large.

That same summer of 1988, V.S. Naipaul visited Jackson during a tour of the American South that resulted in his travelogue A Turn in the South, which was published the following February. Naipaul, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2001, had by that time achieved international recognition as an observer of post-colonial politics and societies. It was in this vein, that of an observer, that Naipaul visited the South, ostensibly to compare it to his own Trinidadian background. Though the issue of race was of obvious interest, the importance of race seems to move further to the background as the work progresses, and Naipaul finds himself increasingly preoccupied with describing the culture of the South, including country-western music, strict Christianity, Elvis Presley and rednecks. This shift of focus seems to take place largely in the section on Mississippi. Entitled “The Frontier, the Heartland”, his visit to the state is for the most part restricted to Jackson, where he becomes captivated with a character he calls Campbell, from whom he received a description of rednecks that fascinated and entranced Naipaul to the extent that he seems to become obsessed (he describes it as “a new craze”) with rednecks not merely as a group or class of people, but as almost a separate species; when someone tells him that “There are three of your rednecks fishing in the pond,” he “hurried to see them, as I might have hurried to see an unusual bird . . .”

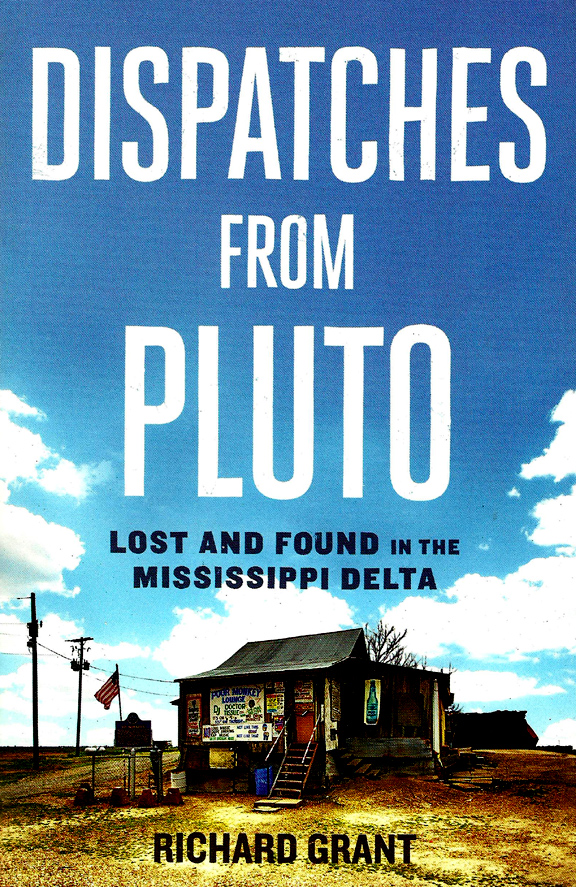

Then we have Richard Grant, whose primary if not unique distinction among outside observers of Mississippi is that he did not “just pass through”. Grant is still here, though no longer in Pluto. He also sounds like a nice fellow, and his tale of buying a home on the fringes of the Mississippi Delta has a somewhat beguiling innocence about it, reminiscent of that involving a certain young lady who fell down a rabbit hole. Indeed, his story has a few other holes in it, not the least of which is why Grant, a British travel writer formerly based in Tucson but living in New York decided to “buy a house and move to Mississippi”. Some might find simply visiting here in character for a travel writer; after all, Mississippi, a state of overwhelming poverty with a stratosphere of commanding wealth, does have a perverse sort of attraction for people in search of something off the beaten path as well as a solid claim to have produced one of the most enduring and influential musical genres of any century, but the most embarrassing legacy of blues music and one augmented by Delta writers themselves (no surprise there) is the myth of the Delta as “the most Southern place on earth”, when in reality it’s just as full of “poverty, faith and guns” as any other neck of the woods between Annapolis and Austin. Three clues as to why Grant came to Mississippi to live and write are his friendship with a Delta food maven with a national profile whose well-to-do father just happened to have a high-end fixer-upper to sell in a hamlet on the eastern bank of the Yazoo River, a pixilated party with the Usual Suspects at Square Books in Oxford and Grant himself, a talented and hard-working writer with an ear for blues music as well by all appearances a bit of capital and no small amount of time on his hands. If those aren’t compelling components for a new book about the Mississippi Delta, then I challenge you to fabricate more plausible ones.

Grant is a fine writer with an amiable voice, but there’s a lot to get past in Dispatches from Pluto. He understands the intensity of isolated people and knows that in such empty places minds fix on petty matters, but in Mississippi he seems to have lost his compass on what is petty and what is not. Granted, travel writers should employ a degree of objectivity, but at some point the observer must become engaged, and throughout this book I kept asking myself, “Where is Richard Grant?” The answer is that he was making a living on many levels, steadily at work not only on what eventually became Dispatches but also on any number of other projects, including making the house he bought habitable, an effort that took an increasing amount of time and money, surely trying not only his patience but that of his long-suffering companion Mariah, not to mention Savannah. His engagement with the Mississippi Delta is in the most basic sense one of making do and getting by, one to which by his own accounts he as a free-lance writer is well accustomed and one well understood by Mississippi’s native residents. It’s worth suggesting that this is the reason he came and stayed, though there’s far more to it than that. A man such as Richard Grant does not lead a simple life.

This is not to say that all else in Dispatches is window-dressing, but much of it can be dismissed as such. One reads a great deal about the people, places and things in the Delta that any Mississippian or for that matter most people in the South or even the nation might find iconic to the point of cliché; the same tired recitation of the rich, sophisticated upper crust and poor, simple lower crust, the same circuitous itinerary of colorful towns and villages, the same boring assortment of restaurants, juke joints and run-down architecture as well as the obligatory nods to racial tension, a whole slew of blues musicians, firearms, possums and raccoons, alligators and snakes, cotton, sweet potatoes and catfish. In Dispatches from Pluto you won’t find any airy odes to the union of earth and sky or muddy elegies on the preponderance of the past; such things are no doubt within Grant’s ability, but that’s just not his style. He is a journalist at heart, a documentarian, if you will.

Curtis Wilkie likens Dispatches to Innocents Abroad, which might be more apt than it appears on the surface; Twain was of course far from innocent, and one suspects that Grant’s placid detachment is a mask for the sort of ferocious cynicism Twain himself often employed, but cynicism doesn’t seem to be Grant’s style either. He is a camera with a finely-ground lens, and this is why you should read this book, particularly if you are from Mississippi: to see Mississippi through the eyes of another person who came here not to deride or ridicule but for an account of how it is being here, or in Eliot’s fortuitous phrase, to explore and perhaps arrive where we started and know the place for the very first time.