A History of Belhaven – Part 3, The Middle Years (1926-1965)

This is a third in a series of articles on the Belhaven neighborhood by Bill and Nan Harvey. In it we look at some of our early institutions and neighbors who frequented them. Some are gone, some still remain; here’s their history.

Miss Eudora Welty (1909-2001) is generally acknowledged as Belhaven’s greatest literary treasure. A writer of true greatness and internationally recognized in that regard as well as for her Depression era photography, she was our neighbor on Pinehurst who shopped at Jitney 14, studied in our libraries, and visited along the sidewalks of our neighborhood.

There are hundreds of stories about Miss Welty, her gentle manner, and sly sense of humor. I have my own. Some of you remember the “hippie days”, when Beatle emulating young people wore their hair long, donned love beads and sported Nehru jackets. There was a restaurant at the end of South Jefferson Street which shall remain nameless, whose proprietors were of the old school. One summer evening Miss Eudora was escorted by two Belhaven College students to the establishment for dinner. The owners took one look at the young men and ordered the trio out. “We don’t serve men with long hair,” they proclaimed. Miss Welty thanked the restaurant owners and departed. Frank Hains, arts and entertainment editor for the Jackson Daily News, heard of the incident and wrote a scathing column in which he demanded an apology. Although the article could not have benefited the restaurant owners, Miss Welty defended the restaurant saying it was their right (then) to refuse service. When asked if she would return under different circumstances she smiled and evoked one of her favorite expressions, “We’d be fools if we didn’t.”

There was no facility to service automobiles in early Belhaven. Residents had to go downtown for gasoline, oil changes and minor repair work. However, that changed in 1928 when a little one pump gas station, designed by Jackson architect Hays Town was built at the northwest corner of Poplar and Hazel Streets. Through the years the little station, which resembled a miniature version of a colonial home, sold petroleum products, nostrums and notions until it closed in 1969. Architects Thomas Goodman and Sam Mockbee adapted the old station to their needs in 1978. According to Goodman, Mrs. Mathew O’Riley a Belhaven third grade teacher, named it “Shady Nook”.

Shady Nook was a way station for the neighborhood kids. Belhaven architect Bob Canizaro who lived on Kenwood, recalls he used his grass mowing money to buy fudge sickles there. Bill Harvey would meet other neighborhood kids on Saturday morning at the Nook to air up his bike tires, grab some Nabs and head for Laurel Street Park. But it was also once a popular hangout for Belhaven coeds as it sold ice cream, candy, soft drinks, peanuts, bobby pins, toiletries and….cigarettes. Today it serves as the office for Henry LaRose Realty. There were many things young ladies had to be shielded from in the 30’s and 40’s and not the least of these were cigarettes. We didn’t know as much about those things then as we do now and after all, Bogie and McCall smoked in their movies; they were stars so it had to be cool. After classes and on weekends, a few of the more daring young ladies from the college slipped down to Shady Nook to light up. No teachers or housemothers were present. Sophistication abounded. It was their refuge.

Throughout the late 1920’s and early 30’s Belhaven continued its eastward growth. Streets which had been named for individuals were now being named generically. Streets west of St. Ann and St. Mary were established but Piedmont, Howard, Divine, Myrtle, Belmont and Ivy were still in the process of being developed. One little street which ran from Riverside to Belmont no longer exists – a victim of the new interstate which eliminated it in the early 1960’s. That street was Enterprise and deserves a place in our history.

Enterprise Street

Whatever happened to Enterprise Street

One short block from head to feet.

From Belmont down to Riverside,

Eight little Houses side by side.

Like Persimmon and Olive Streets

It was one block long and 30 feet deep,

Like bigger brothers it was a part

Of children’s laughter after dark.

No curb or gutters or walk-alongs,

Just a row of Craftsman homes,

The pavement was of crushed grey slate,

Where boys and girls would roller-skate.

Over thirty years it had its place

Near the park it once did face,

And when it lost out in sixty-one

Its memory lies where the traffic runs.

Short and sweet was Enterprise Street,

No longer here for us to greet,

But like other pieces of our past

Its presence here will always last.

There are still mysteries on our streets. Some neighbors remember the little private library on the south side of the 2000 block of Laurel where concrete steps led to a side building no longer there. Where was Vinegar Bend? Was Poplar Boulevard designed to be a true boulevard with a median and sidewalks? Intersecting sidewalks leading into Poplar stop short of the street itself. Was that public land to be part of Poplar? Why was Persimmon never developed east of Greymont? Early maps show it going through to St. Ann. Were there walkways bridging the dead ends of Monroe? Where did Euclid get its name? Did Milsaps students name it for the father of geometry? Does anyone know?

In 1925, Belhaven Heights Part 2, an irregularly shaped subdivision, was platted. The subdivision bordered the Belhaven campus on the west, from Poplar north four blocks to Laurel, along St. Mary and St. Ann Streets opening up a much larger area going north to Riverside Drive and east from the college to Myrtle. Within this subdivision Jackson land developer L.L. Mayes saw an opportunity for affordable housing for young families. Mayes began the development of the Sylvandell subdivision in the late 1920’s and many of its homes of varied architectural style can be found on the east side of the 1400 block of St. Mary Street and around the southeastern corner of Laurel to what was then called Sylvandell Park.

Other developers were discouraged by the rough and hilly terrain but not Mr. Mayes then living with his family in a neoclassical home on Pinehurst. In addition to building homes he commissioned sculptor Joseph Barras, to design a concrete

Pan and his friends have gone back to the flocks and shepherds from whence they came and the little footbridge, children’s statues and walkways have returned to the soil. The creeks run quietly and children still play in the park but if you look carefully along the driveway at 1331 St. Mary, you will see Pan with his flute, a paean to what exists today, a subdivision whose beauty can be found nowhere else in our neighborhood.

Nearby additional developments were taking place. The Belhaven Park subdivision which includes Pinehaven, Parkhurst and River Park, platted 11/3/1939 by the Presbyterian Church USA. The Belvoir subdivision which includes Belvoir Place and Circle was platted 6/26/51 by the Belhaven College Board of Trustees. What was once the northern end of Belhaven Lake is now a sinuous tree lined street of stately homes, some the former residence of families who planted the live oaks along Riverside Drive.

The State of Mississippi owned large tracts of real estate in downtown Jackson and in the early 1800’s made land available to religious denominations in the vicinity of Smith Park. Several local churches located in this area and remain today but the Presbyterians felt preordained to exchange their tract for land at the northwest corner of State and Yazoo Streets. There they worshiped until relocating to 1390 N. State in August, 1951. The land on which the church rests today was owned by a group of developers in 1925. These were early Jacksonians S.S. Taylor, C.E. Klumb, S.K. Whitten, Jr., W.N. Watkins and H.V. Watkins. The group sold the land on December 4, 1925 to W.N. Cheney, R.S. Dobyns, Carl L. Faust, W.E. Guild and Stokes V. Robinson. The Pinehaven Realty Corporation purchased the property from this group for $12,700 on March 1, 1927. For much of the following 23 years the Pinehaven Realty Corporation maintained the land where the church stands today. A single dwelling and out building were shown on the 1925 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map. The majority of the land between Pinehurst and Belhaven Streets was vacant and remained so until purchased by the church on September 20, 1950. Prominent Belhaven resident Chalmers Alexander was instrumental in this transaction.

According to Jackson native Judge Swan Yerger, much of the north end of the 1300 block of North State was a field which served as a softball diamond for the older Power School boys who spent their recess and many hours after school on this diamond.

Two great accomplishments of First Presbyterian Church are its unwavering support of Belhaven University which ensured its survival and prosperity throughout many years and the establishment of the First Presbyterian Day School in 1965. Regardless of your religious persuasion, First Presbyterian Church is a cornerstone in our neighborhood. It draws young families to its day school, students to its chosen university and Christians to its message. In the words of John Calvin (1509-64), “Let us not cease to do the utmost so that we may incessantly go forward in the way of the Lord; and let us not despair of the smallness of our accomplishments.”

Jitney Jungle did not begin in Belhaven but it found a home here. W.B. McCarty and Jud and Henry Holman were cousins who came to Jackson from Greenwood and opened a small grocery in 1912 at the intersection of Adelle and Grayson (Lamar) Streets. They invested a borrowed $1,000 in their business and called it Jackson Mercantile Company. Through the teens and twenties of the 20th century the young men expanded their grocery businesses, even adopting a popular slogan “Save a nickel on a quarter”. According to Mr. Will McCarty, Bill McCarty, III’s grandfather, the owners were looking for a name a bit catchier than a mercantile company. Even the later McCarty-Holman Stores nomenclature was a bit prosaic. It was a habit of Judge V.J. Stricker who lived nearby to invite the three young merchants residing at Mrs. Josephine Bailey’s boarding house on Adelle Street to his home for Sunday dinner. The merchants asked Judge Stricker to suggest a new name for their stores.

The end of the First World War saw returning soldiers anxious to buy an old car for riding about town. They called it a “jitney”, slang for a London taxicab and street jargon for a nickel. Since a cab ride to town in Jackson as well as London cost a nickel the term “jitney” was popular and it was customary for patrons to shop with “nickels jingling in their pockets”. With the store’s slogan in mind and stock in the new stores looking like “a jungle of values”, the judge suggested the merchants rename their enterprises Jitney Jungle Stores. The first store under the new name was at 423 E. Capitol Street which opened April 19, 1919. Now you know.

The 1930 Jackson City Directory shows the birth of our neighborhood Jitney Jungle on Fortification in that year. It was the 14th store in the chain and its first manager was Charles Alford. The new store was small but was developed into a “super store” through a remodeling and a formal grand opening on November 10, 1933.

Mrs. Betty Edwards, daughter of co-founder William B. McCarty said that the Belhaven Jitney made a special point of catering to women. ”When you entered the store there was a platform area to the left for ladies to sit and visit before they shopped. A woman taught knitting and ladies could sit or read. It had the first female rest room in a Jackson grocery store. There were chairs for children and inexpensive house dresses for sale in racks near the front entrance.” Ladies from some of Jackson’s most distinguished families shopped regularly at Jitney 14. They included Mrs. Emmitt (Marie) Hull, Mrs. Fred Sullins, Mrs. James Canazaro, Mrs. R.E. Kennington, Miss Eudora Welty and Mrs. Percy Weeks, Willie Morris’ grandmother, who lived across Jefferson Street. Willie spoke of the store in his 1989 book Homecomings – A Return to Christmas Gone

Throughout the years Belhaven’s neighborhood Jitney Jungle continued to expand, modernize and enjoy commercial success until it was purchased by a northern conglomerate in March 1996. It was later bought out by Winn-Dixie and in 2005 by Greg and Kathy McDade. In 1996, the Jitney Jungle chain’s sales volume was $1.2 billion¬, quite a return on the $1,000 investment by three young entrepreneurs 84 years before.

Growing up we called them the “pink apartments”. The flamingo-colored complex spanning the eastern side of the 1200 block of Kenwood was constructed in 1938 by Jackson architect James T. (Jack) Canizaro. What makes these units unique today is the period they represent once providing homes for some of America’s greatest generation. In conversations with Mr. Jack’s son Bob, who lives in Evanston, IL, we learn that the architecture is Art Moderne, a style copied from homes in southern California. Bob Canizaro spoke not just of the residence built by his father, that he grew up in, but of the times themselves.

“Many tenants came and went in our apartment building. There was a Dutch couple, Colonel and Mrs. Von Oven, who lived there during World War II. He was in the Royal Dutch Air Force in training at Hawkins Field. The Dutch flyboys were notorious for their antics in downtown Jackson, often flying low down Capitol Street and waving at the girls in the high rise office buildings. A woman who worked for us heard a loud noise one day, looked out the kitchen door and saw the colonel flying down Kenwood Place.” No small wonder we won the war.

Mr. Canazaro spoke of other military personnel who lived in his family apartments. “I was fond of a tenant named McGehee. He and I were regulars at the old Jackson Senators baseball games. We were close to Dr. Estelle Maguira who lived in our middle apartment. After she left, William Fulton, former director of Mississippi Public Broadcasting moved in.”

Bob and I discussed the neighborhood around the apartments as it was back in the 1940’s. He remembers Mr. and Mrs. Ellis Wright, Fred and John Reimers, John Hanley Walsh, Robert Stockett, Kirby Walker, Guy Lowe, John Potter, Gilmer Spivey, Bernard Meltzer, Tupper and Doug Drane, Howard Shannon and many others. He spoke of Mrs. Downing’s kindergarten at Poplar and Jefferson, Power School, Stockett Stables, playing ball on the Reimers “back forty” where the Kennington Home was built. He told of rubber gun wars playing in the “big ditch” which is now Belhaven Park, catching lightning bugs in a bottle and going for ice cream and sodas at Shady Nook.

There were sights and sounds then which have faded into history: the lonely whine of the GM&O diesel locomotive, the starting whistle at the Buckeye Oil Mill, lawn mowers cutting grass for money to buy comic books at Cain’s drugstore, animal sounds from the far away Jackson Zoo and the early morning cries of street vendors as they plied their wares down Manship.

The Pink Apartments are filled now with new families and young moderns seeking their own place and dreams. I would hope as they stroll the sidewalks down to Poplar or up to McDade’s they will reflect on the art of Mr. Jack Canazaro, his legacy to our neighborhood, and the times in which he lived.

Jackson, like much of America, entered its golden years in the 1950’s. Far sighted mayors Leland Speed and Allen Thompson were rapidly building a city approaching a population of 100,000. The great war for democracy had been won and with bubble gum, cars, and affordable housing once again available there was no end to what a free people could do to ensure a prosperous future.

On the northern edge of the Belhaven neighborhood, Bailey Junior High School opened in1938; winning national awards for its architectural style developed by Hays Town. The State Medical Center held its first classes on the old Highway Patrol property in 1955. Ike was president, Governor Hugh White was balancing agriculture with industry in Mississippi and the lights did not go out on Jackson’s Capitol Street until long after midnight. Meanwhile, a skinny kid from Tupelo walked into a recording studio in Memphis and sang a song for his mother that changed the course of American popular music forever.

A one-story frame commercial building with a flat roof, home of the Overby Company, sits on 1808 North State. But like so many structures that have endured 90 years it wasn’t always so. It opened as North End Grocery in 1928, named for the northern terminus of the street car line, and served a number of small commercial enterprises before becoming North State Pharmacy in 1947. It was a typical drug store, owned by a Belhaven couple whose surviving widow wishes to remain anonymous. It was the place to go before and after classes at nearby Bailey for its soda fountain and pinball machine. I have to confess, I was there myself, quite often as a teenager, in the early 1950’s. Many years later I sat down with the lady who was the co-owner and she told me a story I will share with you.

In the middle 1950’s there was no interstate system around Jackson. Highway 51 ran down North State into downtown. A traveler going let’s say from Memphis to New Orleans had to pass by North State Pharmacy and Mr. Dixon’s Texaco Station next door. One spring day in 1956 someone did.

Elvis Presley once visited the Belhaven neighborhood. Not for long but forever. My friend smiles today in remembrance of all the things we were and while the drugstore never had a jukebox, it did serve a milkshake to the king of rock and roll.

Our next section will show how our neighborhood matured with expanded residential and commercial growth, a dynamic education system, increased medical facilities, a theater for the performing arts and a strong network of foundations and associations that would ensure its future.

© Bill and Nan Harvey

Shack Screen

The Tangents Onstage

Parchman: A Review

Documentary photography has been an instrument for social reform since Jacob Riis, who focused the nation’s eyes on the grinding poverty of New York City slums in How the Other Half Lives (1880), inspiring the work of photographers who seek to depict history as well as comment on society. A branch of this genre, prison photography, is by nature dramatic and controversial, focusing on the human condition in confinement (at times awaiting execution) and though their ability to convey the reality of prison as opposed to the projected feelings of the viewer is dubious, the images are inevitably stark and gritty, grim and sullen.

Taking photos of Parchman Prison is like shooting fish in a barrel; it’s a given that the results will be iconic on a documentary level. While it’s arguable that the cruelties and injustices at Parchman are no more heinous than in any other penal environment, this is after all Mississippi’s state prison and carries a particular notoriety for that singular reason. But with Rushing’s Parchman what we have is a failure to communicate; the photos are technically precise, yet without resonance, more substance than style and not edited to bring emotion. The lack of angles, of effective use of light, shadows and contrast is evident; often the quality is purely that of straight-on recording, which in most cases is lifeless and banal, with no finesse and less feeling. The inclusion of text from the subjects (albeit in the form of images) undermines an emphasis on the photographs themselves, leaving us with a definitive visual record of Parchman in the 1990s, which is nothing to deride in terms of an historical document, providing an appropriate companion volume to two significant books about Parchman that appeared in the 90s, Taylor’s Down on Parchman Farm (1993) and Oshinsky’s Worse Than Slavery (1996), but nothing to acclaim in terms of art.

This is University Press of Mississippi’s second foray into the field of prison photography; in 1997 it published Ken Light’s Texas Death Row, which followed on the heels of Light’s Delta Time (Smithsonian Institution Press; 1995). Yet even given the lack of effectiveness in the photographs, it’s reassuring that University Press of Mississippi is still on top of their game; though it has at times dropped the editorial ball, when it comes to putting together a quality product, University Press can and has given Rushing’s photos good framing.

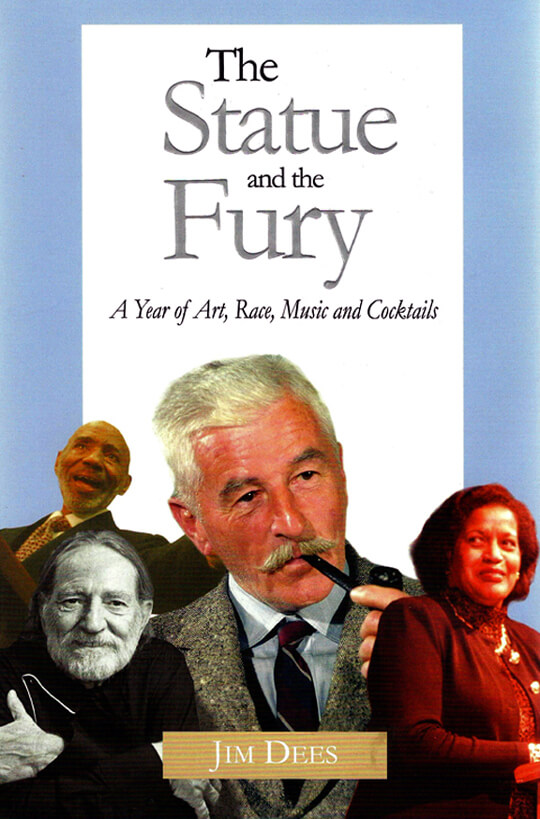

The Statue and the Fury: A Review

I really wanted to like this book, I really did. I was hoping that Dees had matured since publishing Lies and Other Truths (Jefferson Press, Oxford; 2008) an ill-advised assortment of self-absorbed musings, and The Statue and the Fury (Nautilus Press, Oxford) does have an initial premise of objectivity, but this grounding proves to be nothing more than jumping-off point for another lengthy exercise in self-indulgence. The Statue and the Fury could well be described as a roman à clef with no need for a key, since the names come one after another rat-a-tat-tat like a perfunctory roll call of characters, encompassing everyone of note in Oxford during the late 1990s and many who are still there.

In reporting on the tempest in a teapot created over cutting a magnolia on the Oxford Square to make way for a statue, the only character that gets more play than Jim Dees is William Faulkner, said statue subject, who figures prominently on the cover in the company of Willie Nelson, James Meredith, and Myrlie Evers below a vermeil title in a clumsy Monty Python-esque montage. We shouldn’t find this depiction surprising, since Faulkner is Oxford’s most important asset aside from the University of Mississippi, and the others are of course Mississippi icons in their own right, even Willie. Dees goes so far as to share his thoughts on Faulkner’s works in a Catherine’s wheel of maritime metaphors, including, “I would direct first-time readers to the novellas in Go Down, Moses or the Snopes trilogy, or, to dip your toe gently in the Faulkner sea, page-turners like Intruder in the Dust or As I Lay Dying.” Not, perhaps, the most perceptive advice, but then Dees with uncharacteristic modesty admits that he is “not any kind of Faulkner know-it-all”. (Indeed.)

Dees can be engaging on air as well as in person (provided you’re not on the wrong side of his toxic wit), but while his writing displays a formidable command of the first person singular, its sardonic tone is rarely laugh-out-loud funny, even when describing events fraught with high comedy such as Pizza Bob on the witness stand. In short, the entire work concerns nothing more than a “You had to be there” sort of situation in a feeble attempt at gonzo journalism and the title is either an ill-advised tongue-in-cheek pun or a painfully fumbled riff on Faulkner (six of one, half a dozen of the other). Dees’ Lies and Other Truths as well as They Write Among Us (Jefferson Press, Oxford; 2003) to which he wrote the introduction, both sold out, and it’s certainly likely that unless an unrealistic number of copies were printed The Statue and the Fury will as well, particularly if everyone mentioned buys a copy.

By dint of his gig as host of “Thacker Mountain Radio”, which no less than Dees himself refers to as the “Grand Ole Opry of literature”, Dees has become a media figure. Given his unremarkable publishing history, what we’re left with in The Statue and the Fury is an example of marketing based on the appeal of personality; in a sense, buying Dees’ book is somewhat the Mississippi equivalent of buying that collection of Kim Kardashian’s selfies. If you are a fan of Jim Dees, you will certainly find this book worth every penny, and if you lived in Oxford during the ‘Nineties, even if you’re not mentioned, you might buy it, too, but sooner or later it’s bound to be available at your local library.

The Tangents: Wellsfest 2008

Mickler’s Revolt

By 1986 publishing was already wedded to celebrity so much so that the best-selling cookbook that year was by “The Frugal Gourmet”, an ordained minister who was convicted of molesting teenage boys some years later. But Smith, for all his faults, was an international media presence, while Ernest Matthew Mickler (God rest his sweet soul) who in the same year published White Trash Cooking, was a dying man with a vision.

Ernie insisted on the title, which left him an open target since his simultaneously unblinking and winking approach to the stereotype of the rural South confounded people across the country as well as people on the Redneck Riviera. The only thing even remotely resembling a precedent for White Trash Cooking was written by another Floridian, Zora Neale Hurston, whose studies in anthropology brought her back home, much as it did Mickler, who threw down a gauntlet, insisting that while the nation might profile Southerners as a whole as white trash, the behaviors that earmark anyone anywhere as decent, perhaps in cases even honorable, hold sway in the American South as well, a region that is no more tragic than any other section of the country. He also knew that people outside of the South consider us low and mean, but we are (as they are) a layered society undeserving of their unilateral condemnation; our culture, our manners, our morals all have as much a measure of civilized imprint as those of our fellow countrymen, but instead of embracing our differences, they persist in considering the South and its people worthy of their collective opprobrium.

With White Trash Cooking, Mickler opened a portal of discovery into the essential character not only of the South, but of the nation; white trash cooking uses cheap ingredients, commercially frozen, dried or canned, few seasonings, packaged mixes, plenty of salt and sugar, lard and margarine in dishes that are quick and easy to cook, unsullied by any degree of sophistication. It remains the most basic form of cooking in the nation, the cooking of people who don’t read Bon Appetit, people who work a forty-hour week (or more) at a poorly-paying job with little or no insurance, living from paycheck to paycheck, struggling to make a life for themselves and their children. They wouldn’t go to a Whole Foods store unless they lived next door and had to, which is good advice for anybody without an attitude. White Trash Cooking celebrates a significant surface of our many-faceted country, one we should all recognize as uniquely ours and none others. Love it.

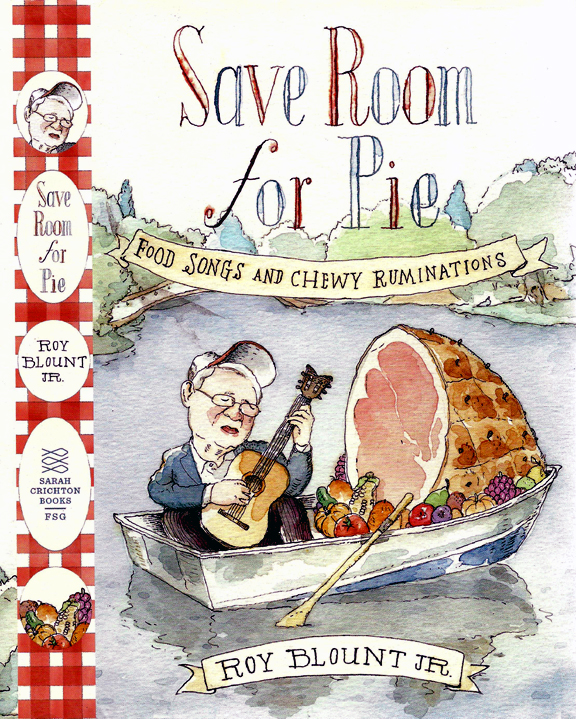

Save Room for Pie: A Review

With 47 books under his belt, it’s a wonder Roy Blount, Jr. can dish out another helping, but Blount is always ready with a serving of his special brand of eclectic linguistic hijinks, and Save Room for Pie has plenty and to spare. In this jaunt to the center ring, Blount takes on food, and as a native of Decatur, Georgia, his take has a decidedly Southern perspective.

Blount’s prose is riddled with non-sequiturs, often to the point of distraction; in fact, the entire work is a hodge-podge of anecdotes, stories involving food and the many celebrities with whom he has rubbed elbows (who are legion), light verse and sidebars. We shouldn’t expect a humorist to give us anything resembling a straight-forward narrative, and Blount not only meets but surpasses these expectations, which can be wearying in a work spanning 280 pages.

Not to say that Blount isn’t entertaining; he takes on dietary guidelines and healthy eating with his tongue firmly planted in his cheek. “Inside every thin Southern person,” he claims, “is a fat person signaling to get out.” He states that Velveeta has “more protein and fewer bad fats than many real cheeses” (being made of whey), and says that he has heard good things “from authorities recognized by my wife” about watermelon, egg yolk, cane syrup, lard, oysters, beef (“if raised right”), whiskey hot peppers, coffee, (dark) chocolate and butter.

His light verse covers such subjects as hamburgers, grease, eggs, gumbo, “love apples” (tomatoes), grits, catsup, “A Dark Sweetness” (cane syrup) and of course peaches. Among the more entertaining essays are on gizzards (“”The gizzard is what a chicken has instead of teeth.”), “Mississippi Music Notes” (“Did I mention that ‘Put Down the Duckie’ is the greatest music video ever made?”) and “Eating Out of House and Home” (“I’ll tell you what’s good though. Baked beans without a fly in them.”), though many of the others are just as rife with Blount’s own brand of lightly sardonic humor.

Admittedly, I am not a great fan of Blount’s writing; I prefer his off-the-cuff performances on NPR’s Wait, Wait…Don’t Tell Me!, but while with Save Room for Pie Blount loads the plate with a lot of superfluous sides (earthworms and professional bass fishing, for instance), the book is a great addition to any fan’s library, a light-hearted jaunt through Southern foodways, a worthy read if only to discover that Mary Hartwell Howorth puts lawn clippings in her pimento cheese.