Salter also created covers for works by Jack London, Graham Greene, Dos Passos, and E.M. Forster.

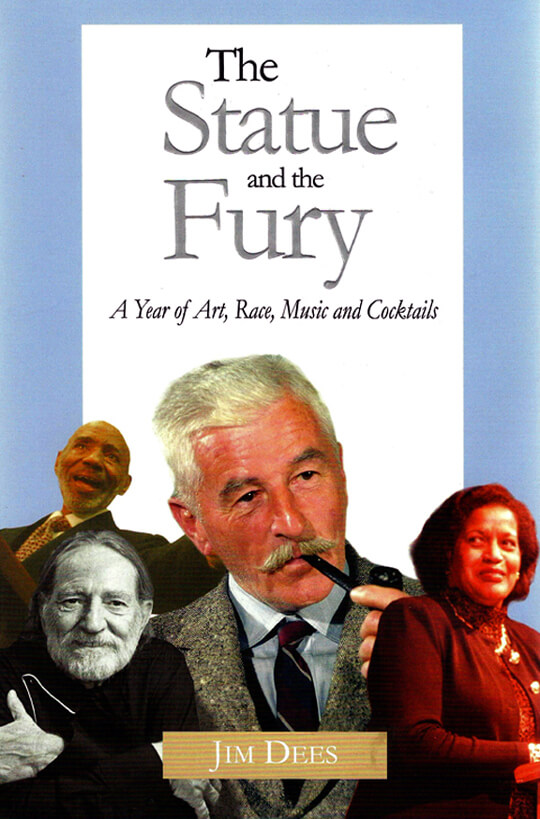

The Statue and the Fury: A Review

I really wanted to like this book, I really did. I was hoping that Dees had matured since publishing Lies and Other Truths (Jefferson Press, Oxford; 2008) an ill-advised assortment of self-absorbed musings, and The Statue and the Fury (Nautilus Press, Oxford) does have an initial premise of objectivity, but this grounding proves to be nothing more than jumping-off point for another lengthy exercise in self-indulgence. The Statue and the Fury could well be described as a roman à clef with no need for a key, since the names come one after another rat-a-tat-tat like a perfunctory roll call of characters, encompassing everyone of note in Oxford during the late 1990s and many who are still there.

In reporting on the tempest in a teapot created over cutting a magnolia on the Oxford Square to make way for a statue, the only character that gets more play than Jim Dees is William Faulkner, said statue subject, who figures prominently on the cover in the company of Willie Nelson, James Meredith, and Myrlie Evers below a vermeil title in a clumsy Monty Python-esque montage. We shouldn’t find this depiction surprising, since Faulkner is Oxford’s most important asset aside from the University of Mississippi, and the others are of course Mississippi icons in their own right, even Willie. Dees goes so far as to share his thoughts on Faulkner’s works in a Catherine’s wheel of maritime metaphors, including, “I would direct first-time readers to the novellas in Go Down, Moses or the Snopes trilogy, or, to dip your toe gently in the Faulkner sea, page-turners like Intruder in the Dust or As I Lay Dying.” Not, perhaps, the most perceptive advice, but then Dees with uncharacteristic modesty admits that he is “not any kind of Faulkner know-it-all”. (Indeed.)

Dees can be engaging on air as well as in person (provided you’re not on the wrong side of his toxic wit), but while his writing displays a formidable command of the first person singular, its sardonic tone is rarely laugh-out-loud funny, even when describing events fraught with high comedy such as Pizza Bob on the witness stand. In short, the entire work concerns nothing more than a “You had to be there” sort of situation in a feeble attempt at gonzo journalism and the title is either an ill-advised tongue-in-cheek pun or a painfully fumbled riff on Faulkner (six of one, half a dozen of the other). Dees’ Lies and Other Truths as well as They Write Among Us (Jefferson Press, Oxford; 2003) to which he wrote the introduction, both sold out, and it’s certainly likely that unless an unrealistic number of copies were printed The Statue and the Fury will as well, particularly if everyone mentioned buys a copy.

By dint of his gig as host of “Thacker Mountain Radio”, which no less than Dees himself refers to as the “Grand Ole Opry of literature”, Dees has become a media figure. Given his unremarkable publishing history, what we’re left with in The Statue and the Fury is an example of marketing based on the appeal of personality; in a sense, buying Dees’ book is somewhat the Mississippi equivalent of buying that collection of Kim Kardashian’s selfies. If you are a fan of Jim Dees, you will certainly find this book worth every penny, and if you lived in Oxford during the ‘Nineties, even if you’re not mentioned, you might buy it, too, but sooner or later it’s bound to be available at your local library.

Chris Sartin: Keeping It Real

At first, I was trying to buy Walker’s Drive-In; I really wanted that place badly. I’d become such a fixture in there, I could feel my personality taking over, and it seemed only natural to get it, but the deal didn’t work out, so I started looking around for a place to put Sartin’s, or rather Sartain’s, since my last name is French, and I wanted to get into classic French cuisine. I went to Blockbusters in Castlewoods to drop off a movie, and I saw the Little Caesars next door was for sale. I just looked at it and though I could do my own pizza place. So I called the guy, Johnny Solomon, who owned all the Little Caesars and Popeyes in the area. He said he wanted $50,000 for the place, I offered $30,000, he came back with $35,000, and that was it. I started with $35,000. My dad loaned me the money out of his house equity. This was 2000. We opened February 7, 2001.

I decided I was going to open a pizza place, and when I realized I could do that, what with the casualness of the atmosphere, I realized I could simply be who I wanted to be and not worry about cutting my hair or what clothes I wear and putting off the customers. I decided I would make the theme of the place the music of the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead, the blues, the jam scene of the Sixties and Seventies because I had to be in there a hundred hours a week and why not enjoy myself while I’m there, hang up the pictures I like on the wall, almost make it like my college dorm room. It was almost accidental, how it all came together. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I was 30 years old. I had tried the insurance business; my dad and his brothers were very successful in it, and somehow that’s what I figured I’d always end up doing, but I just didn’t like it. It’s not that it’s a bad business, it just wasn’t for me. I was an artist; I needed to write, paint, sing, play, cook, and that’s what I needed to do to be happy. My Dad got behind me, and I’ll never forget that. That was a big deal, it meant a lot to me. He had the money to get me started at the time. He wasn’t wealthy when he was growing up and had to work to earn everything he got, all the brothers did, so he wasn’t going to just lay it out there for me. But this seemed like a safe thing; if it failed, it would sting to lose $35,000, but not change his life.

And it went off like a rocket. I think people wanted something real. Also, there wasn’t another gourmet pizza shop in Jackson at the time. I don’t think at all. We made everything from scratch, had some great music playing. It helped that we were next door to a Blockbusters at the time, which was before Netflix and all that. I had two guys in the kitchen, and I took some of the recipes that I knew from Walker’s, like the crawfish bisque and a bread pudding, you know the bread pudding that Miss Hazel baked and I would watch her. I took a little bit of something from everywhere I worked, brought it to the table and went to my guys and said, “Alright, let’s do this.” The recipes have changed up since then. The pizza dough now is nothing like it was back then. Now it’s a 300-year old French artisan recipe. We used everybody who was there and pulled upon their knowledge and experiments. Over the years I changed things to make them better, particularly the pizza crust, which I wasn’t happy with in the beginning. We sold a lot of pizzas and people loved it, but I wasn’t satisfied with it. I think in retrospect it was really the ovens, not the recipes, so now that’s why I have brick ovens in every location. I changed up the recipe and moved forward.

We moved into Hal & Mal’s in ’02. Malcolm would come into Soulshine at Castlewoods for some reason, and you didn’t see him that often outside the city limits. We started talking, and I kept thinking about it because I often hung out at Hal& Mal’s, thinking there was room there for a Soulshine. They weren’t using that back room all the time, and so I said, “Hey, man, we’ll open up a Soulshine at Hal & Mal’s. He loved the idea. Hal and Charly didn’t like the idea, they didn’t have anything against us, they just saw trouble coming, and they were right. My first idea was to pay rent and have the bar in there, but you can’t buy two liquor licenses under one roof, so I said how about I don’t pay any rent, you sell the liquor, and I’ll keep a crowd in this room for you. I’ll make it worth it to you just for me to be here and you can sell all the alcohol you want based on my customers. And that was okay, but it still wasn’t worth it for both parties.It didn’t make sense. Then there was a lot of partying going on, and that’s really what made it fail. I learned a lot of lessons. I pulled out of there after being mugged for a third time in Jackson. My car was broken into, I was losing money and on top of that, I just wasn’t sure what I was doing and everybody was partying. There were other factors, too, but it might have worked if I’d known what I was doing, but if I’d known what I was doing, I’d never have gone there to begin with, nothing against Hal & Mal’s.

Anyway, I decided to go out to Highland Colony Parkway because I could see it all going there. I could see the future. We were the first restaurant out there. I signed a lease in ’04, we opened in ‘06. It took a year and a half. I just knew that’s where the white-collar world was headed, you could see it happening. There was nothing there, just this one little center that I’m in which is a big development now. But I could just see it coming. I believe in the township; I thought it would be cool to live there, like being in Belhaven in the Fifties. I could walk to the grocery store and this and that. So I got there, and it was too soon. I lost my ass for a little while. Once again, I really didn’t know what I was doing, I just had a great idea and I could talk to people and put out good food, make sure the place was clean, but when the business shuts down, when you’re through serving people, when all the food it put up, there’s still a lot of work to do, in the office, at the bank, with your attorneys, whoever it is, and I didn’t know anything about it. And what’s maybe even worse, I didn’t want to know anything about it. I just wasn’t interested in it.

Really, I’m just a glorified bartender at forty-six, and that’s alright with me. I’m not special; I just feel like I had a dream, and I was willing to lay it all on the line to either lose it or end up ultimately happy. I was willing to lose everything because I was literally just miserable. As an artist, you know that if you don’t create, you’re miserable. I had to create in some shape or form. A couple of years into that store, we just weren’t where we needed to be. That area still hadn’t developed yet. We got there too soon. So that’s when I went to Porter & Malouf and asked them to be my partners, to back me and help me with the business end. I’d been going out to Tim Porter’s house cooking pizzas in a brick oven at parties, so I went to them and said, “I need help.” They love me and they love the place, and they decided to do it. When I realized how backed up I was, it turned out to be a substantial investment, which surprised both me and them, but they were in. They stepped up to the table, and we became partners. That was 2008, and we’ve been together ever since.

Once we got some organization, the business really took off; we caught up on taxes and bills that had me behind the eight ball. The story was that I moved the Hal & Mal’s location to Highland Parkway, which was the way I spun it to the press, but that was bullshit because I was just a failure there. I shut it down, but I knew what I was going to do in Ridgeland, so I spun it off to the public as “We just had to get out of Jackson.” We eventually took off in Ridgeland, and it’s been great ever since. We moved from Castlewoods to Old Fanin, then we moved out Lakeland Drive again, now we’re out there in a big place right on Lakeland Drive. It’s done really well, and I’m really pleased with it. Those people out in the Reservoir community have been eating Soulshine pizza for fifteen years. They’ve been really good to me. I grew up out there.

When I first opened the original location in Castlewoods, it was just strictly a to-go Little Caesars spot. My mother, my sisters and I went in and painted and made it cool. I put the stereo in, took all the Little Caesar’s stuff down, played music over the speakers in the kitchen and then I decided to put in a dining area. People kept saying that they needed a place to sit and the bay next door in the center where we opened was available, so I got it, put tables in there, built a little makeshift bar, put in a few TVs, and I’d actually bartend and wait on every table myself. And everybody who came in, most of them I knew, had known them for years and years, and if I didn’t know them, I got to know them really fast. It was a magical time. I was doing what I believed in and that was really all that mattered. The people liked the food, they liked the music; they liked the way they got treated. It was all about service, and it was all about art, expression, and I didn’t think about much else. I still don’t think about much else. That’s why I have partners. You have to worry about it, you have to get involved, and they push me to get more involved, but it’s hard to get anyone who’s forty-six years old, ADD, an artist a musician, writer and songwriter to sit down at a computer and go through a P&L. It’s hard for me to do because I don’t have a natural interest in it; I just make sure it gets done.

Why Oxford? There are a lot of reasons and one of the reasons is you have to get your partners to buy into it, but my partners are Ole Miss guys, and I knew they’d like it. Everybody wants to do something in Oxford, but what most people don’t realize is that Oxford really isn’t Oxford unless a ball game is going on, at least when it comes to retail. Everybody’s there for whatever big occasion is going on, but on a Tuesday in July, what are you going to do? It’s better now that people are moving there to retire. This coming April we’ll have been there for four years. The anniversary is April 20th (4/20). I opened it up on that date on purpose. We didn’t have our kitchen quite ready, but I opened up and served hot dogs that night so people would come in and drink and our anniversary would be 4/20. That makes it really easy for me to remember, because I never remember dates, and the number spans the culture of Soulshine. But the Oxford location has been fabulous, has kicked butt. When we cleaned up the floor of that location, stripped off the years of filth that had built up, we discovered that the site was once the location of one of the first Kroger’s in the state. It took my breath away. I’ll never forget looking at that and thinking wow this is history here. I’m a history major, and any time I can put in a Soulshine, and I only have four, I strive to keep that historical significance if possible, that feeling of realness, I don’t want them all to be alike. I’m always torn over how many I’m going to have and keeping it real, not being a sell-out.

The music is still relevant, and there’s still good music that comes out. You’re always going to have people listen to that kind of music; it might not be the masses, but the music is still there. The music is timeless. I didn’t call it “artisan pizza” back then; I didn’t call it anything. It was just Soulshine, and it still is. I don’t like to call it anything else. It’s always going to be Soulshine pizza, and now we’re making the switch to stone-baked. As I’ve gotten older, I’m not Mr. Detail still, but I’m also striving to get better. To be up where we need to be, I felt like we needed to take the cooking method to another level, to another tier, and that’s what we’re doing this year with the ovens to match everything else, which seemed to be so perfect. And I felt like you look on the internet now and you see brick-fired, coal-fired, wood-fired and felt like we needed to do that. And we have; we have a brick oven in Oxford and Nashville, and we just installed one in Flowood last week. All I have to do now is to install one in the Ridgeland store, and it will take a couple of weeks before we do that. I feel like that gives me the confidence to move to another fifteen years and look up when I’m sixty-one and say, “Yeah, okay. What’s next?”

If I had to look back on life, the last fifteen years of my life and the hardships I’ve gone through, from divorce to being broke, broke, broke, somehow I dug in and made it happen Soulshine has meant so much to me. It wasn’t just a restaurant that I opened up that could fail or be successful. It’s my life on the walls. Everything means something to me, the customers will always mean something to me, the music, everything. It meant more to me than money or my perceived success. But ultimately, in the end, taking care of the people and what I believe in paid off for me down the road. I consider myself a success now. I still think I’ve got a lot of room to get better, and I think that’s what drives me a lot, too, that I’m never satisfied; not with me, or the business or whatever. I’m satisfied that I’m living the life I’ve always wanted to live in certain ways, but I’m competitive. I’ve always been athletic, and I was out there playing tennis until I was forty and wanting to win.

So I think my competitive nature pushes me. I wasn’t going down, and I wasn’t going to let anybody take me down. I also felt like I owed it to the people not to give up; the people who came in there, the people who supported me and the people who worked for me, who had jobs. There were many times when I could have come in on a Monday and said to hell with it, it’s not worth it anymore. That happens all the time in the restaurant business, people just give up. But I’ve never let it go, and I still won’t. It’s me not letting go of myself, which is a big part of my identity and who I am. Sometimes people say your job should not be who you are or whatever, but I turned my job into who I was. I sell myself. When you open up a restaurant, people are going to come see you because you are who you are and it’s about you, but after they’ve eaten there enough times, maybe had a bad meal or two, and you’re having trouble, they just quit coming. They’ll be there to hug you when you close, but the food has to be good, too. And it has been. I’ve never been quite satisfied with it, but I doubt if I ever will be.

I decided to open a Soulshine in Nashville because my oldest daughter lives there, and I knew after being remarried and having two more daughters, I wanted them to be raised together. So we moved there after we opened in 2011, in Midtown near Vanderbilt. It’s a killer place; we have a rooftop patio with a stage up there. The Who’s Who list of legendary musicians and current stars who sit in there with our Soulshine Family Band is very deep. Once I was singing, and I look up and there’s Steve Tyler, for instance. Another time I’m standing in there around Halloween. I see this cat and I’m thinking, “Is that Billy Gibbons or is this dude in costume?” Well, it was him. This stuff happens all the time. I’m floored all the time by who walks in and tells me, “This place is cool, man, Nashville needed something real.” Maybe that’s what I want to have on my tombstone:

Brother Chris Sartin lies here.

“He kept it real”

Ron Shapiro

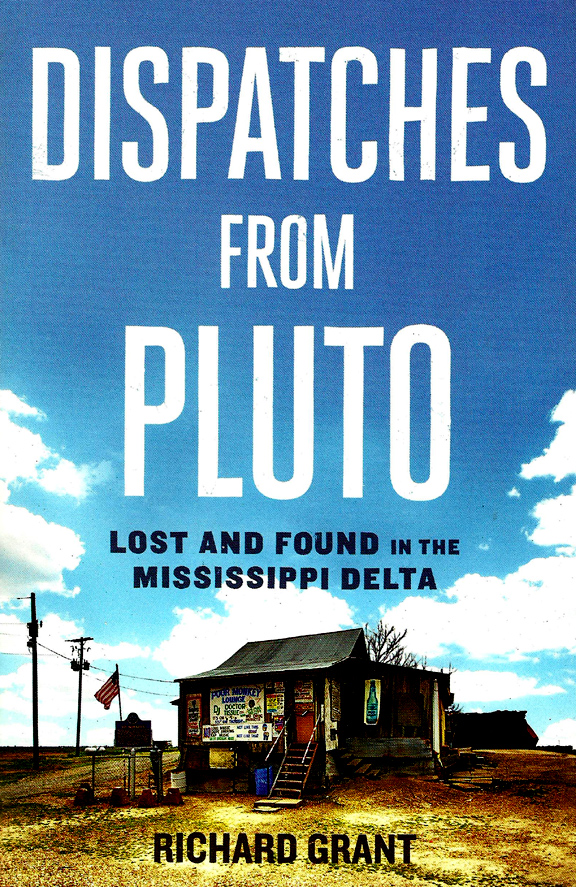

Dispatches from Pluto: A Review

Parochialism is endemic in rural America, and though Southerners are of a naturally hospitable nature, they and Mississippians in particular have an acquired sense of xenophobia engendered by their brutal treatment at the hands of outsiders, most especially writers. In the case of Mississippi, perhaps the most stupefying recent example of such mistreatment comes from Bill Bryson, a native Iowan and former chancellor of Durham University, U.K., who recounts his visit to Mississippi in The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America, in which Bryson chronicles a 13,978 mile trip around the United States in the autumn of 1987 and spring 1988. Bryson’s tale of his journey through Mississippi is as full of bile as most American writers who venture south, packed with shopworn stereotypes and clichés, saturated with ridicule and derision. He left Mississippi with impressions of the state that are what we have come to expect of most people who visit with baggage consisting of preconceived prejudices and with no desire to do anything more than capitalize upon the surety that their condescension would be well-received by the world at large.

That same summer of 1988, V.S. Naipaul visited Jackson during a tour of the American South that resulted in his travelogue A Turn in the South, which was published the following February. Naipaul, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2001, had by that time achieved international recognition as an observer of post-colonial politics and societies. It was in this vein, that of an observer, that Naipaul visited the South, ostensibly to compare it to his own Trinidadian background. Though the issue of race was of obvious interest, the importance of race seems to move further to the background as the work progresses, and Naipaul finds himself increasingly preoccupied with describing the culture of the South, including country-western music, strict Christianity, Elvis Presley and rednecks. This shift of focus seems to take place largely in the section on Mississippi. Entitled “The Frontier, the Heartland”, his visit to the state is for the most part restricted to Jackson, where he becomes captivated with a character he calls Campbell, from whom he received a description of rednecks that fascinated and entranced Naipaul to the extent that he seems to become obsessed (he describes it as “a new craze”) with rednecks not merely as a group or class of people, but as almost a separate species; when someone tells him that “There are three of your rednecks fishing in the pond,” he “hurried to see them, as I might have hurried to see an unusual bird . . .”

Then we have Richard Grant, whose primary if not unique distinction among outside observers of Mississippi is that he did not “just pass through”. Grant is still here, though no longer in Pluto. He also sounds like a nice fellow, and his tale of buying a home on the fringes of the Mississippi Delta has a somewhat beguiling innocence about it, reminiscent of that involving a certain young lady who fell down a rabbit hole. Indeed, his story has a few other holes in it, not the least of which is why Grant, a British travel writer formerly based in Tucson but living in New York decided to “buy a house and move to Mississippi”. Some might find simply visiting here in character for a travel writer; after all, Mississippi, a state of overwhelming poverty with a stratosphere of commanding wealth, does have a perverse sort of attraction for people in search of something off the beaten path as well as a solid claim to have produced one of the most enduring and influential musical genres of any century, but the most embarrassing legacy of blues music and one augmented by Delta writers themselves (no surprise there) is the myth of the Delta as “the most Southern place on earth”, when in reality it’s just as full of “poverty, faith and guns” as any other neck of the woods between Annapolis and Austin. Three clues as to why Grant came to Mississippi to live and write are his friendship with a Delta food maven with a national profile whose well-to-do father just happened to have a high-end fixer-upper to sell in a hamlet on the eastern bank of the Yazoo River, a pixilated party with the Usual Suspects at Square Books in Oxford and Grant himself, a talented and hard-working writer with an ear for blues music as well by all appearances a bit of capital and no small amount of time on his hands. If those aren’t compelling components for a new book about the Mississippi Delta, then I challenge you to fabricate more plausible ones.

Grant is a fine writer with an amiable voice, but there’s a lot to get past in Dispatches from Pluto. He understands the intensity of isolated people and knows that in such empty places minds fix on petty matters, but in Mississippi he seems to have lost his compass on what is petty and what is not. Granted, travel writers should employ a degree of objectivity, but at some point the observer must become engaged, and throughout this book I kept asking myself, “Where is Richard Grant?” The answer is that he was making a living on many levels, steadily at work not only on what eventually became Dispatches but also on any number of other projects, including making the house he bought habitable, an effort that took an increasing amount of time and money, surely trying not only his patience but that of his long-suffering companion Mariah, not to mention Savannah. His engagement with the Mississippi Delta is in the most basic sense one of making do and getting by, one to which by his own accounts he as a free-lance writer is well accustomed and one well understood by Mississippi’s native residents. It’s worth suggesting that this is the reason he came and stayed, though there’s far more to it than that. A man such as Richard Grant does not lead a simple life.

This is not to say that all else in Dispatches is window-dressing, but much of it can be dismissed as such. One reads a great deal about the people, places and things in the Delta that any Mississippian or for that matter most people in the South or even the nation might find iconic to the point of cliché; the same tired recitation of the rich, sophisticated upper crust and poor, simple lower crust, the same circuitous itinerary of colorful towns and villages, the same boring assortment of restaurants, juke joints and run-down architecture as well as the obligatory nods to racial tension, a whole slew of blues musicians, firearms, possums and raccoons, alligators and snakes, cotton, sweet potatoes and catfish. In Dispatches from Pluto you won’t find any airy odes to the union of earth and sky or muddy elegies on the preponderance of the past; such things are no doubt within Grant’s ability, but that’s just not his style. He is a journalist at heart, a documentarian, if you will.

Curtis Wilkie likens Dispatches to Innocents Abroad, which might be more apt than it appears on the surface; Twain was of course far from innocent, and one suspects that Grant’s placid detachment is a mask for the sort of ferocious cynicism Twain himself often employed, but cynicism doesn’t seem to be Grant’s style either. He is a camera with a finely-ground lens, and this is why you should read this book, particularly if you are from Mississippi: to see Mississippi through the eyes of another person who came here not to deride or ridicule but for an account of how it is being here, or in Eliot’s fortuitous phrase, to explore and perhaps arrive where we started and know the place for the very first time.

Jere Allen: Portrait, 1969

Kudzu Kings: Ruling Funktry

Kudzu Kings began their reign on a stretch of Harrison Street that descends east of Lamar down to South 14th through and into Oxford’s arguably greatest band venue, fostering ground for a rockin’ Southern music culture.

At the top of the hill, Proud Larry’s; at the bottom, The Gin—the matriarch of Oxford’s bar scene—and in between was Ireland’s (later Murff’s, and now Frank & Marlee’s). While Ireland’s has been unjustly derided as a “blue-collar bar” and because of its lack of pretention (pool tables, dart boards, and Lance snacks) had its share of bubbas bellied up to the bar, at any given time you’d find people from all walks of life there swilling beer (among them Larry Brown) and at night listening to some of the best music in Oxford.

Singer and rhythm guitarist Tate Moore and bass player Dave Woolworth, affectionately known as “Kudzu Dave,” who had a weekly gig at Ireland’s, hooked up with electric guitarist Max Williams, formerly of The Mosquito Brothers, a New Orleans-style funk band. Williams drafted Mosquito Brothers drummer Chuck Sigler and keyboardist Robert Chaffe. “We merged both bands because Tate was playing with Dave, doing the acoustic thing,” Williams said. “So I was like, ‘Hey, I know some other cats that know how to play music, why don’t we just make a band out of it?’” They were soon joined by George McConnell, a co-founder of Beanland, Oxford’s premiere band during the late 80s and early 90s.

“We were still doing a house band sort of thing every week at Ireland’s, which was pretty much a bar locals went to, our friends,” Williams said. “But little by little the college kids started to realize how much fun it was, and they started coming too. Soon we had all kinds of people having fun and that’s when we started having to find places big enough for everybody.”

“It was Mondays at the Gin, Tuesdays at Ireland’s,” Chaffe said. “Every week, that was a given; Larry’s would be somewhere in the Thursday, Friday, Saturday mix. “We had a lot of gigs in the early days, and we developed a good chemistry early on. Packing the Library (a large venue west of the Square) came a bit later.”

“When I was with Beanland, we were trying to be the Tangents,” McConnell said. “With their soul, their camaraderie, their stage presence, they were a huge influence on me when I got here to Ole Miss in 1981, and when I caught them at the Gin, I was like, ‘Who ARE these guys?’ They were the Bad Boys from the Delta, man. They could play those old songs as well as anyone could, plus they did it with their own style. Beanland had some legendary shows with the Tangents at Syd & Harry’s; we’d swap sets, but they always closed the show and ended up mopping the floors with us. That carries on with the Kudzu Kings, so we’re going to do a couple of Duff’s songs, ‘Peace Lily of the Valley’ (about a bend in the Sunflower River) being one of them, another being ‘234’ (a room number at the Holiday Inn in Greenville).”

Kudzu Kings (1997), their debut CD, was produced by Grammy Award-winner Jim Gaines. In his review at Allmusic.com, Richard Foss said, “Picture in your mind a really good country band that has been playing the biker bar scene for a while.

“I want to warn everybody that Dave Woolworth has gathered up jugglers, fire breathers, dancing girls, and nubile young ladies to serve drinks. Not only that, we’re holding a lottery for a tea cart we’ve been threatening to give away for years,” McConnell said. “We’re bringing in about every drummer we’ve ever played with, most all of the guitar players from over the years, lots of guests to sit in throughout the event, trying as best we can to begin with the songs we started with and move through the history of our music. We hope to show that there isn’t a band without progression.”

“It’s only been a good time,” Woolworth said. “In all marriages you grow, and when you’re a band, in a sense you’re married to everybody else. We’re still able to do things together. That’s exciting.”

All photos courtesy of Kudzu Kings.

Leprechauns from Lafayette County

Hill Country Blues

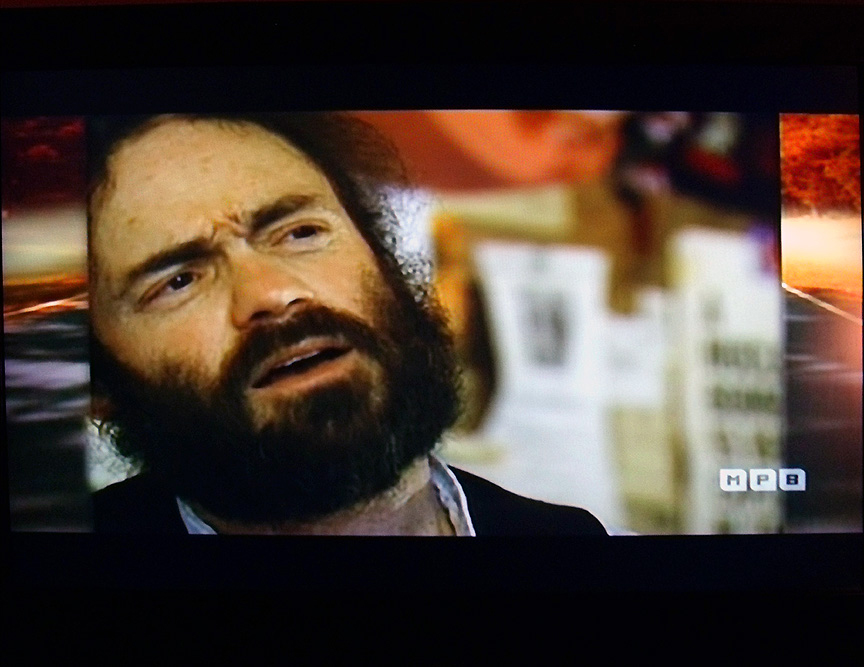

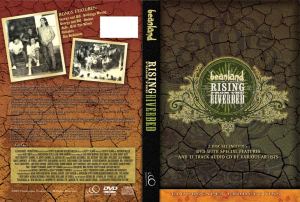

Beanland: Rising from the Riverbed

With Beanland: Rising from the Riverbed, Scotty Glahn and Kutcher Miller have distilled the essence not only of a hot jam band but of a special milieu.

Rising from the Riverbed attempts to and largely succeeds in capturing the freewheeling, lackadaisical and somewhat dissipated spirit of that time and place. This achievement proves to be somewhat of a drawback, however, since the result is a roman à clef best appreciated by those who were there then and know or knew members of the cast of characters. It’s an insider’s view into a seminal period in the cultural life of Oxford. Interviews add to the film’s appeal (Barton made the cut). Nostalgia is not a bad thing, especially when it’s worked out so carefully and lovingly. Allow me to tip my hat to Glahn and Miller not only for recognizing Beanland as worthy of a broader stage, but also their foresight in documenting a very special time in a very special place.