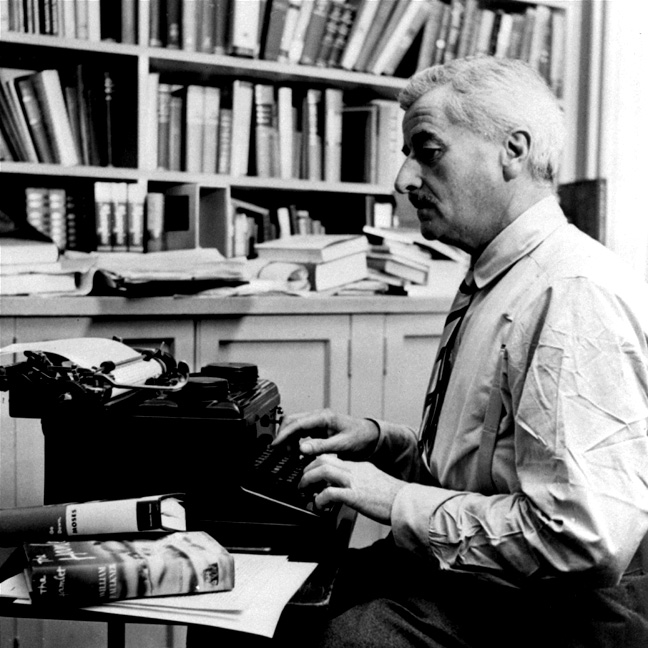

Faulkner’s Writing Habits

This is an excerpt from Bitterweeds: Life with William Faulkner at Rowan Oak, written by his step-son Malcolm Franklin and published in an exclusive edition by The Society for the Study of Traditional Culture in 1977. Franklin is a capable story-teller himself.

One of the most frequent questions that people ask me about Faulkner is about his writing routine and writing habits. Pappy really had no set routine. He worked in an apparently erratic manner. I do know one very important fact. He never carried a notebook or made any notes. He did not at any time carry a pencil or paper. He seemed to work largely from memory and observation.

He had a small portable typewriter that was presented to him by an old sailing friend, Jim Devine, whom he had known in New York in the late twenties. To this very day it remains in what is now known as Pappy’s Office at Rowan Oak. I always associate it with Pappy’s noisy periods, the ones that let us all know Pappy was at work. During what we referred to as his silent days, he used pen and ink. On such days you could not be sure whether he was writing or not. It was all very quiet. No telephone, no radio and no doorbell! These were forbidden items. All you could hear were the sounds from the woods beyond the formal gardens and the barnyard. The dogs would bark. A rooster who had lost the time of day might unexpectedly crow. Cows would occasionally let out a low moo reminding those in charge that milking time was near. Otherwise, only silence; for we were too far from the road and out of the way for the sounds of traffic to interfere.

Then there would be the times I would see Pappy walking along the driveway, perhaps headed for a walk down Old Taylor Road, in the direction of Thacker’s Mountain, some six miles away. It was not out of the ordinary for Pappy to cover the distance between Thacker’s Mountain and back in one afternoon. Quite often I would go along, riding the small quarter horse that Pappy had given me, Dan Patch. Pappy, of course, walked through the woods, and by the time I reached Thacker’s Mountain by the road, there would be Pappy sitting on top of one of the large boulders, perfectly still, not saying a word. I would ask, “Pappy, would you like to ride Dan Patch back and let me walk?” “No,” he would always answer, preferring to go through the woods rather than by the road. Upon returning to Rowan Oak he would not say a word. Instead he would go straight to the library, or to his bedroom, where he had a small writing table. And then you would know he was writing. Even in the silence.

Another trait of his which took him outdoors but was still connected with his writing was squirrel hunting. Every fall, on Saturday and Sunday mornings, and often on weekday afternoons, too, Pappy and I would hunt squirrels—always at least one mile from Rowan Oak. The squirrel we were after in particular was the fox squirrel. Unlike the ordinary gray squirrel, who carelessly slits about, the fox squirrel demands great patience from the hunter, for he will sit perched motionless on a limb for long intervals at a time. The hunter must outsit the fox squirrel. If he waits long enough, in absolute silence, the squirrel will show himself in a vulnerable position. It was during these long periods of utter silence that I believe Pappy did a great deal of his thinking about the plots and characters he was writing about. He never said anything about it. However, many times when we arrived back at Rowan Oak he would say to me, “Buddy, would you dress out my squirrels? Or have Broadus dress them out for me?” I would reply, “Certainly, Pappy,” and then he would disappear, and I would hear the typewriter going for the rest of the morning. Other times he would come on back and dress out the squirrels with me.

We would never have more than two or three each at the most. Pappy brought me up never to kill more than we would need. Further, to make our stay in the woods longer and more of a sport, Pappy and I had a pact where we would only shoot for the head. We kept an old tin tobacco box with a slit in the top. Either of us who hit a squirrel anywhere but the head had to put a quarter in the tobacco box. When it was full, we bought a bottle of bourbon with it. Preferably Jack Daniel’s. Despite the fact that there have been many stories told about Faulkner’s drinking habits, including the statement, in many cases, that he was an alcoholic, he was not. It is a fact that he was a hard drinker. But only on occasion. And during a period of twenty-five or more years of close association, I never observed Faulkner’s drinking heavily while he was actively writing.

Faulkner gave a well-deserved reply to columnist Betty Beale of The Washington Star, whose society gossip column was widely read. She asked for the largest number of words he had penned on one day. His answer, printed in the June 14, 1954 column, clearly showed his attitude when he was asked a stupid question He gave an absurd answer: That he had climbed to the crib of the barn one morning with his paper, pencil and a quart of whiskey, and pulled the ladder up behind him; when daylight began to fail, he realized he had torn off five thousand words. In our barn at Rowan Oak there was no crib overhead—only a hay loft with no retractable ladder.

When he had completed a particularly long and involved piece of writing he would take a Sabbatical, indulging heavily in his favorite bourbon. Perhaps it might last a month or six weeks. Quite often the last week of his binge I would spend driving him around Lafayette, Marshall, Yalobusha and Panola Counties. In the summertime we would drive in my jeep. In the wintertime the excursions would take place in a closed car. He would sit there in the front seat, viewing the countryside. But sometimes he would carry on a very animated conversation with me in which he showed his love for and knowledge of that section of North Mississippi. He would point out places he had drawn on for certain incidents in his books or stories. Thus, I know exactly the location of As I Lay Dying, which is southeast of Oxford on the south side of the Yocona River. The location of one of his best stories, “The Hound”, is northeast of Oxford in the Tallahatchie River bottom, in a locality known as Riverside. On one long drive we made together in my jeep, he said, “This is where ‘The Bear’ took place.” We were passing through the old Stone place, between the Sunflower and Tallahatchie Rivers, some seventeen miles southwest of the old river town known as Panola, situated a few miles north of Batesville in Panola County. It was in the late fall, I believe, and we had been hunting at Mr. Bob Carrier’s plantation, where Pappy took Clark Gable to hunt once in the late 1930s.

On our return trip to Rowan Oak that evening, we travelled along an old, dusty road. Cotton stood on either side of the road, but much shorter and scrawnier than that we had passed earlier, around Batesville and Clarksdale in the Delta country. Pappy had noted there that some of the cotton had been picked by hand, some by machine—this was one of the earliest occasions, if not the earliest, that we had seen machine-picked cotton fields. Now from the road we could glimpse the tops of the trees in the river bottom beyond the fields—just a faint outline against the fast fading evening. From Pappy’s silence I realized, as we had rolled along this country road, that he was headed towards his typewriter again, and that soon I would be hearing once more the tap-tap sounds that so often penetrated the quiet darkness of Rowan Oak at odd hours during the night.

When Giraffes Flew: A Review

Jeff Weddle’s vision encompasses many facets of the human condition—focused rage and conflict, love and lust, the peevishness of petty minds—but for the most part his vignettes confront you with those moments in life when the world shifts a bit, when the things that were in place lose their balance, bringing into focus the law that states life can turn on a can of sardines. Weddle’s stories are about those brief, shining moments in a South of indiscriminate geography, for the most part that of two-lane roads, the landscapes of Flannery O’Connor and Larry Brown, in a sturdy, staccato prose that tell what happens when we come to face the world as who we are, naked and without artifice.

The most powerful stories in the collection are “A Feast of Feathers”, a harrowing story of the loss of innocence; “Hot Sardines”, which delineates a situation packed with potential, a study in lowered expectations that explode into chaos and disorder; “A Constant Battle of the Flesh”, a very, very funny story of tangled lust that ends in the complex complacency many such situations do; “Epiphany”, perhaps best described as a prose poem about “God’s cruelest gift”, insufficient talent; “She Finds Herself Dancing”, a truly beautiful observation/reflection on that magic which takes place when the spotlights are upon you; “Dooley’s Revenge”, retelling that “oldest story” of two men and a majorette; the back-to-back stories of “Dog Day” and “Ditto”, which describe how some people weren’t made to care for others while some care for others too much in the wrong way; and “State of Grace”, a story that defies description but one you will find yourself reading again to find the song behind the words, “I wonder who you are.”

For the life of me, it is my fondest hope that in time the whimsical cover for this dark and perceptive collection of short stories, an image taken from the last story, which in itself is a reflection on theology, perhaps even on the need for theology, will become a collector’s item more illustrative of a publisher’s misconception of a work than it is of the work itself. Jeff Weddle is far from whimsical, and though When Giraffes Flew does have visions of exotic animals cavorting in clouds, nobody has an umbrella.

Dispatches from Pluto: A Review

Parochialism is endemic in rural America, and though Southerners are of a naturally hospitable nature, they and Mississippians in particular have an acquired sense of xenophobia engendered by their brutal treatment at the hands of outsiders, most especially writers. In the case of Mississippi, perhaps the most stupefying recent example of such mistreatment comes from Bill Bryson, a native Iowan and former chancellor of Durham University, U.K., who recounts his visit to Mississippi in The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America, in which Bryson chronicles a 13,978 mile trip around the United States in the autumn of 1987 and spring 1988. Bryson’s tale of his journey through Mississippi is as full of bile as most American writers who venture south, packed with shopworn stereotypes and clichés, saturated with ridicule and derision. He left Mississippi with impressions of the state that are what we have come to expect of most people who visit with baggage consisting of preconceived prejudices and with no desire to do anything more than capitalize upon the surety that their condescension would be well-received by the world at large.

That same summer of 1988, V.S. Naipaul visited Jackson during a tour of the American South that resulted in his travelogue A Turn in the South, which was published the following February. Naipaul, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2001, had by that time achieved international recognition as an observer of post-colonial politics and societies. It was in this vein, that of an observer, that Naipaul visited the South, ostensibly to compare it to his own Trinidadian background. Though the issue of race was of obvious interest, the importance of race seems to move further to the background as the work progresses, and Naipaul finds himself increasingly preoccupied with describing the culture of the South, including country-western music, strict Christianity, Elvis Presley and rednecks. This shift of focus seems to take place largely in the section on Mississippi. Entitled “The Frontier, the Heartland”, his visit to the state is for the most part restricted to Jackson, where he becomes captivated with a character he calls Campbell, from whom he received a description of rednecks that fascinated and entranced Naipaul to the extent that he seems to become obsessed (he describes it as “a new craze”) with rednecks not merely as a group or class of people, but as almost a separate species; when someone tells him that “There are three of your rednecks fishing in the pond,” he “hurried to see them, as I might have hurried to see an unusual bird . . .”

Then we have Richard Grant, whose primary if not unique distinction among outside observers of Mississippi is that he did not “just pass through”. Grant is still here, though no longer in Pluto. He also sounds like a nice fellow, and his tale of buying a home on the fringes of the Mississippi Delta has a somewhat beguiling innocence about it, reminiscent of that involving a certain young lady who fell down a rabbit hole. Indeed, his story has a few other holes in it, not the least of which is why Grant, a British travel writer formerly based in Tucson but living in New York decided to “buy a house and move to Mississippi”. Some might find simply visiting here in character for a travel writer; after all, Mississippi, a state of overwhelming poverty with a stratosphere of commanding wealth, does have a perverse sort of attraction for people in search of something off the beaten path as well as a solid claim to have produced one of the most enduring and influential musical genres of any century, but the most embarrassing legacy of blues music and one augmented by Delta writers themselves (no surprise there) is the myth of the Delta as “the most Southern place on earth”, when in reality it’s just as full of “poverty, faith and guns” as any other neck of the woods between Annapolis and Austin. Three clues as to why Grant came to Mississippi to live and write are his friendship with a Delta food maven with a national profile whose well-to-do father just happened to have a high-end fixer-upper to sell in a hamlet on the eastern bank of the Yazoo River, a pixilated party with the Usual Suspects at Square Books in Oxford and Grant himself, a talented and hard-working writer with an ear for blues music as well by all appearances a bit of capital and no small amount of time on his hands. If those aren’t compelling components for a new book about the Mississippi Delta, then I challenge you to fabricate more plausible ones.

Grant is a fine writer with an amiable voice, but there’s a lot to get past in Dispatches from Pluto. He understands the intensity of isolated people and knows that in such empty places minds fix on petty matters, but in Mississippi he seems to have lost his compass on what is petty and what is not. Granted, travel writers should employ a degree of objectivity, but at some point the observer must become engaged, and throughout this book I kept asking myself, “Where is Richard Grant?” The answer is that he was making a living on many levels, steadily at work not only on what eventually became Dispatches but also on any number of other projects, including making the house he bought habitable, an effort that took an increasing amount of time and money, surely trying not only his patience but that of his long-suffering companion Mariah, not to mention Savannah. His engagement with the Mississippi Delta is in the most basic sense one of making do and getting by, one to which by his own accounts he as a free-lance writer is well accustomed and one well understood by Mississippi’s native residents. It’s worth suggesting that this is the reason he came and stayed, though there’s far more to it than that. A man such as Richard Grant does not lead a simple life.

This is not to say that all else in Dispatches is window-dressing, but much of it can be dismissed as such. One reads a great deal about the people, places and things in the Delta that any Mississippian or for that matter most people in the South or even the nation might find iconic to the point of cliché; the same tired recitation of the rich, sophisticated upper crust and poor, simple lower crust, the same circuitous itinerary of colorful towns and villages, the same boring assortment of restaurants, juke joints and run-down architecture as well as the obligatory nods to racial tension, a whole slew of blues musicians, firearms, possums and raccoons, alligators and snakes, cotton, sweet potatoes and catfish. In Dispatches from Pluto you won’t find any airy odes to the union of earth and sky or muddy elegies on the preponderance of the past; such things are no doubt within Grant’s ability, but that’s just not his style. He is a journalist at heart, a documentarian, if you will.

Curtis Wilkie likens Dispatches to Innocents Abroad, which might be more apt than it appears on the surface; Twain was of course far from innocent, and one suspects that Grant’s placid detachment is a mask for the sort of ferocious cynicism Twain himself often employed, but cynicism doesn’t seem to be Grant’s style either. He is a camera with a finely-ground lens, and this is why you should read this book, particularly if you are from Mississippi: to see Mississippi through the eyes of another person who came here not to deride or ridicule but for an account of how it is being here, or in Eliot’s fortuitous phrase, to explore and perhaps arrive where we started and know the place for the very first time.