Sleepy Corner

Sam, the Garbager, had carpet,

And some scraps of office jot,

Optomacy stooped to throw him,

As he passed from lot to lot,

And with these he decked his cabin

In a rather modern style;

But himself remained old-fashioned

Like–simple and true the while.

And the milk of human kindness

Seemed to bubble from his heart,

As he rolled about the city

In his two-wheeled garbage cart.

S.A. Beadle,

Lyrics of the Under-World (1912),

photo by R. H. Beadle

Calhoun County, Mississipi: A Pictorial History

The Free State of Calhoun

The following article, written by Col. M.D.L. Stephens, appeared in Calhoun Monitor in 1900, was reprinted June 18, 1931 and on in July 6, 1972 The Monitor-Herald. It later appeared in the newsletter of the Calhoun County Historical Society MS, First Quarter, 2000. This colorful account of a traveling circus touring north central Mississippi at the turn of the last century gives you a stiff dose of Colonel Stevens’ wry humor.

In 1856, Old Dan Rice, the celebrated clown and circus showman, made a venture through Calhoun County, striking Benela first, next day at Pittsboro and thence over to Coffeeville. Being a man of extraordinary abilities and sagacious comprehension by nature as well as the experience of extensive travel, it took him no time to discover the prominent characteristics of the denizens of that inland county.

Really he did not expect to find so far out in the interior a class of people so intelligent and independent. Calhoun’s citizenship made no pretensions in those days at style rather on the grotesque order. Such a combination, Old Dan, in all of his travels, had never struck before. Evidently their mark made its impression upon his mind as the independent sovereignty he had ever come across in all of his travels, so much so that at his next performance in Coffeeville the next day, he got off some laughable jokes at their expense, which were heartily enjoyed and applauded by her sister county-men attending the circus that day.

The first one the writer remembers was by Old Dan on his little trick mule in the grand entry, which always captivates the audience into an enchanted trance. I may say as they emerge from the dressing tent, indeed there is a charm about the “Grand Entry” of a circus; irresistible, even with the most stable-minded—the beautiful horses of varied colors, the riders in their dazzling costumes, will surely product the same effect that it did upon St. Peter, when that panorama of four-footed beasts descended to earth from the heavens.

After this parade, leaving the ring-master with his whip in hand, Dan Rice and his mule made possession of the ring to round up this initial act with something ludicrous. He made many circuits around the ring, imitating each round some laughable incident real or imaginary. Finally to close the scene, he humped himself as awkwardly as he could, at the same time remarking, “This is the way the Schoonerites rode into Pittsboro yesterday, coming to see Old Dan.”

Of course this brought forth a yelling applause from the Yalobusians. About the same time, however, the little mule was nearing the exit gap in the ring, apparently tired of the game all at once as if imitating his rider, got a vigorous hump in his own back, and just at the gateway, made a sudden stop, sending the clown forward like a flying squirrel, spreading him out in good shape in the dirt, instantly darting in to the dressing tent.

After a few seconds of suspense, Dan rose, hobbling about as though he was disjointed and a fit subject for the hospital for several weeks at least. At this juncture, the ringmaster in way of reproof said, “Oh, yes, my laddie, see what you get by making invidious comparisons?” To which the clown said pathetically, “Master, do you reckon that dang little mule was taking up for them hossiers in Calhoun County?”

“Why, sir, of course he is; he knew every word you said, besides he has relatives over there, didn’t you see them?”

“Dad drat it, them was the fellows I saw riding that way?”

“Yes, sir,” said the ringmaster.

Cogitating a moment, Old Dan came back to his master, “Say, Mr. Ringmaster, if you wanted to get out of this world without dying, where would you go to?”

“That, sir, is an impossibility; no man can get out of this world unless he dies.”

“No! I know where to get out of this world without dying,” said Dan.

“And where would you go, sir?”

“Why, just over the Schooner, into the Free State of Calhoun!”

The rebel yell followed this enunciation. Many Schoonerites present and their generous natures added in the eclat of that day. In this tour of Dan Rice of Mississippi, The Memphis Appeal had accompanied the show, and reporter and solicitor, and this joke upon Calhoun County seemed to be enjoyed and relished with such tenacity that this reporter sent it to the office and a few days after I read in the humorous column of that paper a verbatim account of Dan’s act in Coffeeville. Afterwards, I heard Old Dan kept the joke all through North Mississippi, which gave the county that notoriety as “The Free State of Calhoun”, and will no doubt follow her through the decades to come. Thus Calhoun County bears that name and is amply able to take care of herself amid exigencies of any sort.

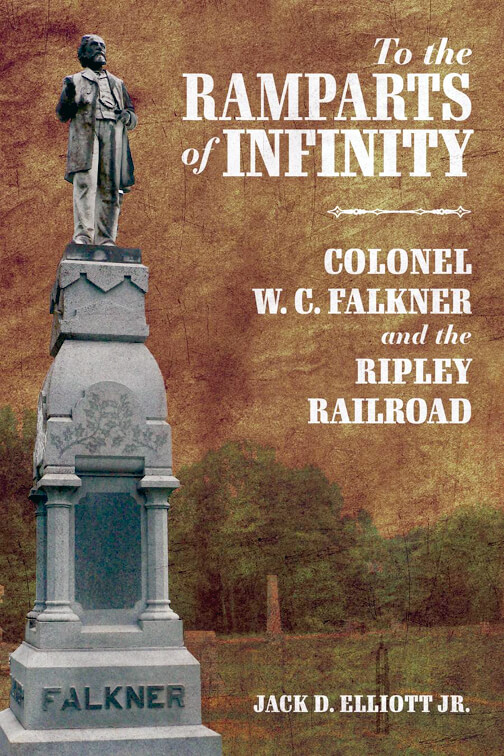

To the Ramparts of Infinity: A Review

With “Sartoris” (1929), William Faulkner began “sublimating the actual into apocryphal,” targeting his great-grandfather, William Clark Falkner, as inspiration for the Yoknapatawpha cosmos and prototype for Colonel John Sartoris.

While it’s the incandescence of William Faulkner that provides the impetus for critics and historians to piece together the life W.C. Falkner, Colonel Falkner was a prominent, if not towering figure in his own right, certainly in terms of the history of north Mississippi, and an archetype of the men who fashioned a nation out of the Southern frontier.

The Yoknapatawpha stories also led Jack Elliott to W.C. Falkner. Elliott first heard about “Old Colonel” Falkner at the initial Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference at the University of Mississippi in 1974, and a field trip to Ripley brought young Elliott to the foot of the nineteen-foot Falkner monument that dominates the cemetery, the actual counterpart to the “apocryphal” monument in the Jefferson cemetery where the marble statue of John Sartoris [gazes] “to the blue, changeless hills beyond, and beyond that, the ramparts of infinity itself.”

In time, Elliott began formulating a work on the life of W.C. Falkner, and found that not only were the stories that circulated about Falkner during his lifetime “fantastic and exaggerated,” these stories themselves were “perpetuated and augmented by short, poorly researched historical pieces.” Elliott sets out to amend these shortcomings, which indeed he does superbly, with a seasoned scholar’s attention to detail and an ear for the written word.

Elliott’s account of Falkner’s early years and the progress of the Falkners and their Word relatives from the eastern seaboard is supported by comprehensive documentation. When the U.S. Congress declared war against Mexico in May 1846, Falkner was elected first lieutenant, which, Elliott confirms, “was certainly due to his popularity among his peers rather than his ability to command.” Elliott provides a thorough account of Falkner’s actions in Mexico, as well as the succeeding Civil War in which he was an officer (“brigadier general, then captain, then colonel and … captain again”) of the Magnolia Rifles, a company from Ripley.

Elliott doesn’t neglect Falkner’s education, stating that he “read law” under his uncles Thomas Jefferson (“Jeff”) Word and J.W. Thompson, and was admitted to the nascent Mississippi bar in 1850. Little else is known of his formal education, though Elliott says that Falkner himself alludes to studying Cicero and Julius Caesar.

Though Elliott’s biography doesn’t stint on a full account of Falkner’s extensive feuds with the Hindmans or with Thurmond, Elliot is determined to discredit earlier portrayals of W.C. Falkner that paint him as a pathological megalomaniac, stating that “The evidence for such a scenario is weak and the conclusion little more than a strained surmise that was bolstered by repetition.” Elliott points out that Falkner was “well-liked by most and even idolized by many,” and that earlier historians (particularly Duclos) “failed to see the feud [with R.J. Thurmond, his assassin] in terms of a conflict over differing visions for the railroad …”

Throughout the work, Elliot provides supporting evidence of Falkner’s character, including this from Thurmond’s great-nephew: “[Falkner] loved power and the trappings of power; he delighted in playing the Grand Seignor (sic), yet was a public-spirited citizen and at heart a kindly if hot-blooded man.”

Another falsehood Elliott seeks to dispel is that Falkner was not the prime architect of the Ripley Railroad, that Falkner managed to inveigle the public into believing that he was the driving force behind the project when in fact he was only one among many who contributed to the scheme. But, though the original charter for the Ripley Railroad Company was issued to W. C. Falkner, R. J. Thurmond, and thirty-five other incorporators in December 1871, the mountain of evidence Elliott presents is far more than enough to convince even a skeptical reader—who are at this late date likely to be few—that it was indeed Falkner “who brought the social, political, and financial elements together and made it happen.”

Elliott examines Falkner’s life in letters with marvelous detail. He gives, for example, an entertaining synopsis of Falkner’s famous melodrama, “The White Rose of Memphis” (1881), complete with contemporary reviews. Digging deeper, he examines Falkner’s less successful second novel, “The Little Brick Church” (1882), and his play, “The Lost Diamond” (1874). Earlier writings—including a sensationalist pamphlet, a narrative poem, and a short novel—also come under review.

Elliott offers insights into Falkner’s writing habits, and documents his familiarity not only with the Bible, but with Shakespeare, Scott, Byron, Homer, and Cervantes. In May 1883, Falkner toured Europe and published an account of his travels, “Rapid Ramblings in Europe” the following year.

What Elliott sets out to do is to “to inquire into the image of a man long dead, an image partly frozen into that of a marble statue.” Elliott’s biography of “Old Colonel” Falkner embraces far more than that life, that image. “As in much of local history, the memory of a place draws us to delve into the matrix of interconnected symbols, whether stories or documents or associated places.”

To that end, Elliott’s work on Falkner embraces not just the man, but the milieu, the town of Ripley and the society and culture—such as it was—of north Mississippi in his day. He includes a fascinating “Field Guide to Colonel Falkner’s Ripley,” a block-by-block examination of the town using the grid established by the surveyor “who in 1836 laid out the streets, blocks, and lots, and this geometry still frames the lives of residents and visitors today.” Filled with historic photos of homes, businesses, and downtown traffic (i.e., cotton wagons and railroad cars), this section of the book will undoubtedly find the greatest appeal among casual readers.

Elliott’s writing is lucid, orderly, and compelling. Perhaps Elliott didn’t consciously set out to write the “complete, sensitive, and discerning biography” of W.C. Falkner Thomas McHaney expressed a need for almost sixty years ago, but, in the end, he has.

Raymond Church

The Cherry Hill – Poplar Springs – Reid Community in Calhoun County, Mississippi by Monette Morgan Young with Introduction by James M. Young

Monette and Tom Young named me James Morgan: James, after both my uncles; and Morgan, my Mother’s maiden name. My parents and my two sisters and I grew up in Calhoun county in north central Mississippi where our ancestors have lived for almost 200 years. I went to three different high schools in the county since Mother had to move about to work as a nurse after my father died unexpectedly in 1946. After earning an engineering degree at Mississippi State and a commission through the Air Force ROTC program, I was called to active duty immediately and became a career officer, spending 28 years before retiring as a Lt. Colonel. My last active assignment was in northwest Florida, and I have lived here ever since.

Mother was born in 1915 and was a lonely only child, her little brother having died shortly after he was born. She grew up on her parents’ isolated small farm in the hills on the edge of the Reid Community in northeast Calhoun county. An early settlement in this area had been called Cherry Hill but it had vanished by the time Mother was born. This area included rich farmland in the Skuna River bottom area and smaller farms in the hills south of the river. The white settlers here were primarily of Scots, Irish, Welsh, and English heritage, coming mainly from Virginia and the Carolinas and traveling through Alabama and Tennessee to get here as the Chickasaw Indians were forced to move to Oklahoma in the 1830s. Most of these arriving families were large, as were needed to raise the crops and cattle needed for basic living. As the number of settlers increased, churches were organized and the small amount of community social life here revolved around Rocky Mount and Poplar Springs Baptist Churches organized in the mid-1800s. Schools were small, one-roomed, one teacher, even in the early 1900s. Monette’s mother Eula was one such teacher at whatever school in the area needed her. During the school months she and Monette often boarded with a local family and got back to their home only on weekends.

Mother loved to read and to listen to older family and friends tell their stories about their growing up days in the 1800s. High schools were beginning to be established and she attended one year at the county Agricultural High School at Derma and then finished her high school at Vardaman, boarding with a local family there. Vardaman High School is where she met Tom Young and they married while both of them were still teenagers. They began their married life in Vardaman and their three children were born there. Tom died unexpectedly in his sleep in 1946 shortly after returning from WWII service and Monette began working to support her children. She became a Licensed Practical Nurse in a small local clinic and eventually moved to Memphis to get a better position.

Her interest in the community and people of her youth continued and was intensified in her middle years. Some of her older kinfolk were also living in Memphis and she began to work with them to learn and document all that they remembered about Reid and the families there. She used the library facilities in Memphis for her research and corresponded widely by phone and mail with folks who had lived in the Reid area or who had information about that area that they would share. She, her cousin Clarence Morgan, and her grandson Jesse Yancy III walked through many of the graveyards where ancestors, kinfolk, and childhood friends were buried. She taught herself to do genealogical research and was one of the charter members of the national Murphree Genealogical Association, her mother’s family line.

Her handwriting was hard to read (she said it was because her mind was so much faster than her writing), so she bought a typewriter and taught herself to type. However, most of the letters she sent me were handwritten because she knew that I could easily read them. Over the years she had occasionally sent me information about our family history and genealogy, but in the 1980s she began to send much more. She said that I might not be all that interested in the history of our family and the community where she grew up, but that my children or grandchildren might. I was impressed by what she was sending and, as my interest grew, I realized that, with a little editing, this material would make a great book.

I began that task as a surprise for her next birthday. It took a while for me to type all that she had sent. I used an early early form of word processor that was available in my job and worked at this after hours and on weekends. After I got it all typed, I went through and rearranged the material into logical groupings and added a few photos and maps and a comprehensive index. I also included a census of the Poplar Springs Cemetery which had been created by her cousin Clarence and his family. She had added a significant amount of genealogical information to this census and it seemed to fit perfectly as an appendix to the book.

I put the information about the families of the Reid area, the history of the community itself, the importance of the Poplar Springs church, and her memories of the community life in the first part of the book. In the second half, I put her detailed memories of her daily life as she was growing up on the small farm during the time of World War I and shortly afterwards.

She was delighted with the book and said that if she had known what I was going to do she would have added this or that and she would not have said this or that. So I revised the book to make those changes and gave her the original and several copies, keeping a couple for myself. She suggested that it be titled “The Cherry Hill – Poplar Springs – Reid Community in Calhoun County, Mississippi”.

Over the following years as people heard about the book, she made about 100 photocopies of it which were provided, for the cost of copying, to anyone who asked for one.

Mother died in February 2000 in Jackson, MS, where she had moved to be near her daughter Barbara. Her funeral was in Vardaman, and I was surprised at the number of people who attended. Many told me that they had not known her, but loved her book and wanted to pay their respects.

A few months later, I updated the book into a second edition to include a few additional changes and a few corrections that she had mentioned, and had 200 copies professionally printed. Copies were donated to the libraries in Calhoun County and to the Mississippi collections at Mississippi State and Ole Miss. The other copies were sold for the cost of the printing. When those had been sold and I found that people were still asking for copies, I made it available through Amazon.com for the price of printing plus a small royalty fee which is donated to the Calhoun County Historical and Genealogical Society. I also made it available for download at no charge as a PDF from several places on the internet.

From reviews and comments that I’ve received from librarians and readers, this book has become a unique and well-regarded resource for information about the history of this part of north Mississippi, of the Reid and Poplar Springs area, and of the people who settled there. It turned out to unusual in the amount of detail it provided about those times and places. One person who bought the book from Amazon wrote: “If you come from this area, it is a must have. I often use this book for reference. Many references to my ancestors among the area. The writing is very easy to read and enjoyable. It is like sitting listening to my grandmother or mom tell stories of the past.”

Visiting Jackson

In this short excerpt from his Journals, artist and naturalist John James Audubon, who knew the older cities of the state on the Mississippi well, describes his only visit to Mississippi’s new capital city on the Pearl.

May 1, 1823 – “I left the bayou on a visit to Jackson, which I found to be a mean place. The hotel atop the bluff was the lowest sort of dive, a rendezvous for gamblers and vagabonds. Disgusted with the place and the people, I left and returned to my wife in Natchez.”

Contemporary visitors echo Audubon’s impressions; Anthony Bourdain called it a “ghost town.” Jackson is still a mean place, in every sense of the word, crippled by petty avarice and racial tension.

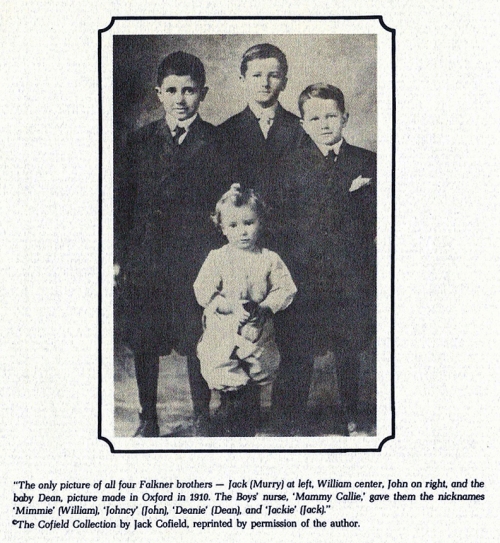

Nannie Faulkner’s Beaten Biscuits

This image from A Cook’s Tour of Mississippi (The Clarion-Ledger: 1980) accompanied an article by Dean Faulkner Wells, “The biscuits Nannie and Callie baked for the boys.” Into 1 qt. sifted flour work well 1 tblespn each lard, butter and teaspn salt. After well worked moisten with 1/2 pt. (sweet) milk and make stiff dough. Beat by hand. Bake quickly.

The Great Spinach Myth

The facts I use to frame my worldview are steadily becoming ash in the burning light of truth. The process seems interminable; just today, I found out about spinach, and the earth quaked a bit.

Whenever Popeye the Sailor Man needs super strength, he squeezes open a can of spinach, pours it down his throat, and turns into a pipe-smoking dynamo. And it isn’t always Popeye who eats the spinach. In one toon, he forces the spinach down Bluto’s throat so Bluto will work him over, and he’ll get sympathy from that slivery wench, Olive Oyl. And in one cartoon, when a Mae West-like competitor is flirting with Popeye, Olive gets fed up, downs some spinach, and beats the shit out of that hussy. Popeye’s creator, Elzie Crisler Segar, gave his sailor the ability to power up by eating a can of spinach because it was widely known that spinach was a superfood that was packed with iron.

The truth is, spinach has no more iron than any other green vegetable, and the iron it does contain isn’t easily absorbed by our bodies. Spinach’s reputation as a super-source of iron began with a mathematical error. Back in 1870, Erich von Wolf, a German chemist, examined the amount of iron within spinach, among many other green vegetables. In recording his findings, von Wolf accidentally misplaced a decimal point when transcribing data from his notebook, changing the iron content in spinach by an order of magnitude. Once Wolf’s findings were published, spinach’s nutritional value became legendary. This error was eventually corrected in 1937, when someone rechecked the numbers. Spinach actually only 3.5 milligrams of iron in a 100-gram serving, but the accepted fact became 35 milligrams. (The miscalculation was due to a measurement error instead of a slipped decimal, but whatever.) If Wolf’s calculations had been correct each 100-gram serving would be like eating a small piece of a paper clip.

The myth became so widespread that the British Medical Journal published an article outlining the laboratory error in 1981, but spinach’s reputation as a powerful iron supplement has only recently diminished. I’d like to think that’s because of kale instead of nobody watching Popeye anymore.