With “Sartoris” (1929), William Faulkner began “sublimating the actual into apocryphal,” targeting his great-grandfather, William Clark Falkner, as inspiration for the Yoknapatawpha cosmos and prototype for Colonel John Sartoris.

While it’s the incandescence of William Faulkner that provides the impetus for critics and historians to piece together the life W.C. Falkner, Colonel Falkner was a prominent, if not towering figure in his own right, certainly in terms of the history of north Mississippi, and an archetype of the men who fashioned a nation out of the Southern frontier.

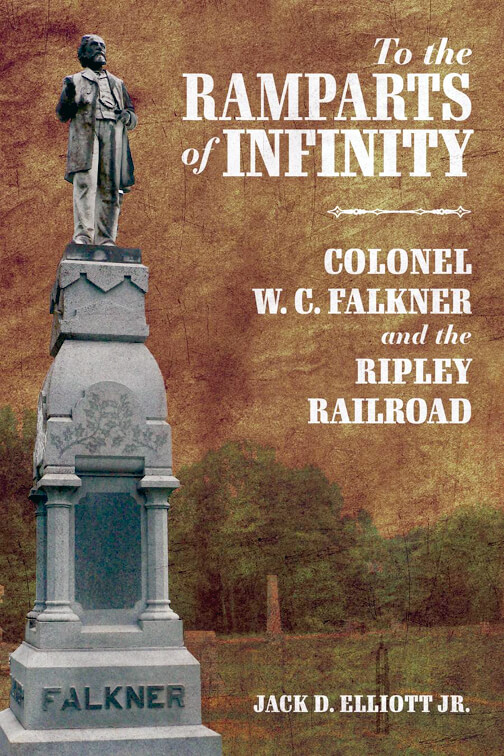

The Yoknapatawpha stories also led Jack Elliott to W.C. Falkner. Elliott first heard about “Old Colonel” Falkner at the initial Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference at the University of Mississippi in 1974, and a field trip to Ripley brought young Elliott to the foot of the nineteen-foot Falkner monument that dominates the cemetery, the actual counterpart to the “apocryphal” monument in the Jefferson cemetery where the marble statue of John Sartoris [gazes] “to the blue, changeless hills beyond, and beyond that, the ramparts of infinity itself.”

In time, Elliott began formulating a work on the life of W.C. Falkner, and found that not only were the stories that circulated about Falkner during his lifetime “fantastic and exaggerated,” these stories themselves were “perpetuated and augmented by short, poorly researched historical pieces.” Elliott sets out to amend these shortcomings, which indeed he does superbly, with a seasoned scholar’s attention to detail and an ear for the written word.

Elliott’s account of Falkner’s early years and the progress of the Falkners and their Word relatives from the eastern seaboard is supported by comprehensive documentation. When the U.S. Congress declared war against Mexico in May 1846, Falkner was elected first lieutenant, which, Elliott confirms, “was certainly due to his popularity among his peers rather than his ability to command.” Elliott provides a thorough account of Falkner’s actions in Mexico, as well as the succeeding Civil War in which he was an officer (“brigadier general, then captain, then colonel and … captain again”) of the Magnolia Rifles, a company from Ripley.

Elliott doesn’t neglect Falkner’s education, stating that he “read law” under his uncles Thomas Jefferson (“Jeff”) Word and J.W. Thompson, and was admitted to the nascent Mississippi bar in 1850. Little else is known of his formal education, though Elliott says that Falkner himself alludes to studying Cicero and Julius Caesar.

Though Elliott’s biography doesn’t stint on a full account of Falkner’s extensive feuds with the Hindmans or with Thurmond, Elliot is determined to discredit earlier portrayals of W.C. Falkner that paint him as a pathological megalomaniac, stating that “The evidence for such a scenario is weak and the conclusion little more than a strained surmise that was bolstered by repetition.” Elliott points out that Falkner was “well-liked by most and even idolized by many,” and that earlier historians (particularly Duclos) “failed to see the feud [with R.J. Thurmond, his assassin] in terms of a conflict over differing visions for the railroad …”

Throughout the work, Elliot provides supporting evidence of Falkner’s character, including this from Thurmond’s great-nephew: “[Falkner] loved power and the trappings of power; he delighted in playing the Grand Seignor (sic), yet was a public-spirited citizen and at heart a kindly if hot-blooded man.”

Another falsehood Elliott seeks to dispel is that Falkner was not the prime architect of the Ripley Railroad, that Falkner managed to inveigle the public into believing that he was the driving force behind the project when in fact he was only one among many who contributed to the scheme. But, though the original charter for the Ripley Railroad Company was issued to W. C. Falkner, R. J. Thurmond, and thirty-five other incorporators in December 1871, the mountain of evidence Elliott presents is far more than enough to convince even a skeptical reader—who are at this late date likely to be few—that it was indeed Falkner “who brought the social, political, and financial elements together and made it happen.”

Elliott examines Falkner’s life in letters with marvelous detail. He gives, for example, an entertaining synopsis of Falkner’s famous melodrama, “The White Rose of Memphis” (1881), complete with contemporary reviews. Digging deeper, he examines Falkner’s less successful second novel, “The Little Brick Church” (1882), and his play, “The Lost Diamond” (1874). Earlier writings—including a sensationalist pamphlet, a narrative poem, and a short novel—also come under review.

Elliott offers insights into Falkner’s writing habits, and documents his familiarity not only with the Bible, but with Shakespeare, Scott, Byron, Homer, and Cervantes. In May 1883, Falkner toured Europe and published an account of his travels, “Rapid Ramblings in Europe” the following year.

What Elliott sets out to do is to “to inquire into the image of a man long dead, an image partly frozen into that of a marble statue.” Elliott’s biography of “Old Colonel” Falkner embraces far more than that life, that image. “As in much of local history, the memory of a place draws us to delve into the matrix of interconnected symbols, whether stories or documents or associated places.”

To that end, Elliott’s work on Falkner embraces not just the man, but the milieu, the town of Ripley and the society and culture—such as it was—of north Mississippi in his day. He includes a fascinating “Field Guide to Colonel Falkner’s Ripley,” a block-by-block examination of the town using the grid established by the surveyor “who in 1836 laid out the streets, blocks, and lots, and this geometry still frames the lives of residents and visitors today.” Filled with historic photos of homes, businesses, and downtown traffic (i.e., cotton wagons and railroad cars), this section of the book will undoubtedly find the greatest appeal among casual readers.

Elliott’s writing is lucid, orderly, and compelling. Perhaps Elliott didn’t consciously set out to write the “complete, sensitive, and discerning biography” of W.C. Falkner Thomas McHaney expressed a need for almost sixty years ago, but, in the end, he has.