John Conway is a young professional with a wife, a son and daughter. He lives in the house he grew up in, a house that sits just over a mile from the banks of the Pearl River.

“I was a child in 1979, and our home flooded, but that was considered an extraordinary event,” he said. “These days, I consider the risk to be pretty low, I guess, though there were some houses in my neighborhood that were flooded last spring.” Conway, his wife and children enjoy living in a city with a river. They enjoy fishing and canoeing, and Conway and his son kayak on the Pearl on weekends. “But the chance for flooding is very real,” Conway said. “Living where I do, the threat is always in the back of my mind.”

His and thousands of others.

* * * * * * * * * *

Initially, the Pearl River served the city as one of its earliest routes to and from civilization. The 1830s were a high water mark in the role of the river as a resource and a reason for the city, but by 1845, rail traffic had been established, and then roads rolled in from all quarters of the compass. Gradually the river fell into abeyance as a platform of commerce for the burgeoning city. But soon the Pearl came to assume a different economic role in the history of Jackson; the bluff could no longer accommodate all of its citizens and buildings began to be erected upon the floodplain. Flooding along the Pearl River in the Jackson area has been a problem since the beginning of the city, but it has been especially noticeable since development has spread into the floodplain. Since then, the river and its urban tributaries have flooded different areas on a periodic basis. Major floods have been classified by their severity according to the frequency at which they are estimated to occur. The 1979 flood has been called a 100-year floodplain event. The 1983 flood was a 50-year event. And the 1991 flood was a 10-year event. It should not pass without notice that all three of these events occurred within a 12-year period.

Ironically enough, given this catastrophe of riches in terms of water, area leaders were discussing the problems of an adequate drinking water supply for Jackson as early as 1926. One of these leaders was State Senator Mitchell Robinson who succeeded in obtaining a flood control and navigability study from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The study proved unfavorable, but Robinson was persistent. Some dismissed his idea of a dam north of Jackson on the Pearl to provide water and recreation for the city as “Mitch’s ditch,” others warmed to the idea. By 1955, Jackson’s water consumption had increased in excess of five times the rate of 1935 and pollution in the Pearl was a mounting problem. The labyrinth of legal and legislative problems and other obstacles that stood in the way of the construction of the Ross Barnett Reservoir are history now, and the reservoir is a pivotal element in the life of the city. But the Reservoir never was really designed for flood control; it was primarily constructed to create a water supply and to provide recreation. Despite that, the reservoir, because of its very nature as an impoundment of water, plays a crucial role in flood control in the lower river basin. According to Kenneth Griffin, general manager of the Pearl River Valley Water Supply District, the Ross Barnett Reservoir presents special problems in that area.

“One of the challenges, and one of the reasons this reservoir is so difficult to manage for flood control is that you have a huge watershed for this size river, this size of control structure,” Griffin said. “Regrettably, even with perfect hindsight, all you can do is to handle something like a 15- or 20-year event, depending upon when it comes. Certainly you can’t handle a hundred-hear or five-hundred year event,” Griffin added. “1979 was a really terrible flood, and we managed that one with very little in the way of rain gauges and stream gauges. We had manual rain gauges, cooperators that would simply call in the precipitation and we did not have any sophisticated software at that time. And even then, I think the people did a very good job, came very close to doing the best job possible.”

But even in the case of reservoirs that are designed to control flooding, the use of impoundments for this purpose has been discredited because of their downstream (and upstream) impact. Flood control reservoirs are set at a specific area in a drainage system to control flooding in an immediate area, but reservoirs impact rivers both above and below their dams. The LeFleur Lakes project is such an impoundment proposal intended to solve the flooding problems in the Jackson area in such a manner that “the attractiveness and growth potential of the metropolitan area would also be enhanced.” The proposal states that flood levels would be permanently lowered in the Jackson-to-Byram area by providing a better flow course for the passage of water and by reducing the rate of flow in the river and envisions the creation of a vital new waterfront district for the Jackson Metropolitan area.

Under the LeFleur Lakes proposal, large amounts of sand from beneath the numerous railroad and highway structures south of downtown Jackson would be excavated. This would be needed in order to provide the proper flow course through this area of the river. The study proposal maintains that existing levees and bridges presently block the river’s flow and back water up into Jackson homes and businesses. To accommodate the excavated material, the Flowood levee would be moved to the east and the dredged material would then be put in the middle of the newly formed lake. This would create a 600-acre island opposite downtown Jackson. North of Lakeland the dredged material would be placed on the east side of the newly formed lake. The newly-created land, an artificial island in the middle of the Pearl near where an extended High Street would stretch, would be accessed by bridges and by constructing interchanges of parkways and city streets over it and along the entire length of the 3000 acre lake. The LeFleur Lakes proposal states that “many roads and bridges are needed at this time to alleviate the metropolitan area’s traffic congestion,” and that both the traffic and flooding problems can be solved simultaneously and at less cost than plans for previous flood control, roads and bridges. The proposal also says that all the structures that flooded in the 1979 flood should be protected from another 100-year flood by the new lake and the improved reservoir discharge procedure. Additionally, the plan would provide that surveying be conducted in order to determine what structures exist in the various flood prone areas that would not be protected from a so-called 100-year flood. If any structures exist that need protection, auxiliary plans would be considered and, if warranted, additional protection would be extended to those structures.

The LeFleur Lakes plan would accelerate the flow course for the river by removing the trees from the very lowest level of the river floodplain (the river bottom land). This level would then be lowered another 5 feet with dredges and other earth-moving equipment, and then the entire 11-mile river course opposite Jackson would be made into a permanent lake. This lake would be necessary to prevent the redistribution of sand and silt and to prevent the regrowth of trees in the river flow course. Naturally, the Ross Barnett Reservoir would play a key role in the project’s success. According to Griffin, “The LeFleur Lakes plan includes two components. Obviously, the lakes themselves are proposed. But the other half of the plan involves some major operational plans in how the (current) reservoir is operated, specifically how the gates are operated.” LeFleur Lakes admits to other drawbacks, as well. For instance, under the proposal, levels in the Ross Barnett Reservoir, on two or three occasions each year, over a period of a day and a half, will fall one foot then rise again to their original level. According to the original Two Lakes website (now defunct), “Once every 25 years they (“Reservoir people”) would be warned to untie moorings and move boats because the level will be taken down below 295 feet. On the positive side, they would enjoy an extra one half to one foot of water in their boat slips” and “would be compensated by knowing that two thousand of their neighbors will never have to worry about their homes and businesses flooding again.” In addition, metal buildings at very low elevations would not be protected from another 1979 flood, but they would be compensated by “having protection from a 100-year flood on structures that probably will not last 100 years.” People who own land and camps on the river south of Jackson would experience “one or two” river bottom floods that they would not have had otherwise, but they would be compensated by the assurance that the new reservoir would have the capacity to take one foot of elevation off of every major flood that could occur in the area. “One foot off of the 1979 flood would have prevented much of the flooding that these people’s neighbors suffered in 1979.”

Supporters of LeFleur Lakes cite the need some sort of flood control and the availability of direct funding for a local agency to undertake the project. Federal commitment to flood control in the Jackson area does exist; otherwise the Corps would not have sought funding for a more thorough and inclusive system of levees, a proposal now called the Comprehensive Levee System of 1996. In April, 1988 the Pearl River Basin Development District asked the Corps of Engineers to initiate alternative flood control studies. The Corps received authorization and funding in February 1989. Federal funds were used for the reconnaissance study which was completed in June 1990. The District agreed to serve as local sponsor for the study for the Jackson Metro area, which took 54 months to complete and cost $3 million. The District provided one-half of this amount in cash and in-kind contributions. A feasibility cost-sharing agreement was signed in September 1991, and feasibility studies were initiated in October of the same year.

The Pearl River Feasibility Flood Control Study (a.k.a. the Comprehensive Levee Plan) was completed by the Corps of Engineers in February 1996. The Corps recommended the construction of 21 miles of new levees at a cost of $122 million. The local sponsor would be required to provide $38 million for the acquisition of land, easements, rights-of-way, relocations and disposal areas. Legislation enabling the Pearl River Basin Development District to serve as the local sponsor for the Flood Control Project was defeated in the 1995 and 1996 sessions of the Mississippi Legislature. The plan also included $30 million worth of recreation amenities and improvements, most of which would have been cost shared. Even before then, in 1984, the Corps also proposed a dry dam that would catch heavy flows from extreme rainfall events in the upper basin, events similar to those which caused the ’79 and ’83 floods. Called the Shoccoe Dam to be installed near Carthage, it was planned at a cost of $80.1 million ($24 million shared). It was identified by the Corps of Engineers as the most comprehensive flood control project for the Pearl Basin. But in October, 1984, the Mississippi House of Representatives defeated a bill authorizing the District to serve as the local sponsor for Shoccoe. Local opposition killed the funding measure, but many people still consider Shoccoe to be the best plan for flood control in the middle reaches of the Pearl.

Everybody has their favorite proposals. “As far as we know, the Comprehensive Levee System (proposed by the Corps) is still viable, but we’ll have to evaluate it again,” Walker said. “We will have to see if the levee alignment is still in place, and we’ll have to see if any development has gotten in the alignment and we’ll have to adjust it.”

“What we’re looking at are the levees and LeFleur Lakes. It’s probable that LeFleur Lakes might turn out different than what it is now. The final result might be some combination of lakes and the levee system. We have several of what we call milestones that we’ll reach as we go through the study. We’ll discuss these with the sponsors, since these will be decision points where we’ll decide whether we need to go forward or not. If we get to the point that something showed up as a “show-stopper,” we would have to evaluate with the Levee Board at that time whether we want to proceed with that plan or do something else. But we could not proceed without them being agreeable to that. There is a consensus that something needs to be done, but the question is what the plan is on how to control it. Public opinion is such that something is needed to control flooding, but we don’t know what the plan is. As to other proposals, as we go through the process, a sponsor will have to sponsor a study for other alternatives. With the proper sponsorship, other plans could be submitted.”

* * * * * * * * * *

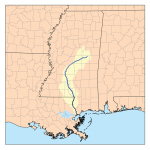

The Pearl River Basin covers an area of about 7,800 square miles, comprising about 16 per cent of the state as a whole. From Neshoba County, the river flows southwesterly, eventually forming the boundary between Louisiana and Mississippi in the southern part of the basin and discharging into the Gulf of Mexico just north of New Orleans. Before the Pearl reaches the Gulf from Jackson, it still traverses some two hundred plus miles, and the lands along the lower river have already felt the impacts of impoundment and flood control in the Jackson Metro area. One of the most serious effects is that of bank erosion, which has been a crucial and continual problem since the development of the state. Andrew Whitehurst, a wildlife ecologist with the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, is the author of the newly-published Mississippi Streamside Handbook, available as a free download from the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks website. Whitehurst said that rivers are able to carry a great amount of sediment. But when a stream goes into a reservoir, it slows down and the energy of the water is dissipated. Much of the suspended material it carries drops out, and the water leaves the reservoir sediment-starved.

“A normal river will gather a suspended load from its bed and from whatever flows in from its tributaries and through normal bank erosion and moving sand bars around,” Whitehurst said. “Our river (the Pearl) is altered. The fact that the discharges can be abruptly stopped after a flood event makes the levels go up and down, so the banks become saturated during floods and when the water is quickly shut off and the level of the river channel drops, the banks can slough or heave.” Whitehurst points out that there are three well-known diadromous (migratory salt-to-freshwater) species that will be impacted by the dams: the American eel, the Alabama shad and the Gulf sturgeon. The maritime connection of the Pearl is another crucial element when flood control anywhere along the river is under consideration, since the wetlands that lie near the mouth of the Pearl are important to the seafood industries along the central Gulf. In a public hearing in Biloxi on March 11, coastal residents expressed concerns that LeFleur Lakes would damage the Coast, especially in terms of the area’s seafood industry. Gulf citizens were particularly worried that the project would reduce the amount of fresh water flowing into the Mississippi Sound, degrading its oyster beds and shrimp population. Lauren Thompson, of the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources, said, “Our concern is with reduced or increased salinity as well as with sediment and nutrient transport down the Pearl River. The reduced flow of nutrients and sediments down the Pearl can change the environmental conditions in the Mississippi Sound, affecting salinity and water quality.

“So it could have a negative impact on oysters, shrimp, blue crabs and finfish. Oysters, which can’t move, have a narrow salinity band. If the salinity is too high, predators come in; if the salinity is too low, the oysters close up, and if they stay closed for an extended period of time, they die.” Since the Pearl empties into the Gulf just north of New Orleans, the State of Louisiana is also keeping an eye on flood control along the river, as it will impact their seafood industry as well as salinity levels in LakePontchartrain.

Apart from the Reservoir, flood control in the Jackson area is also managed by a system of levees built by the Corps of Engineers in the 1960s. These levees serve as buffers for the floodwaters and also funnel the flood downstream. Aside from emergency situations, the levees are largely maintained by local interests. Periodic inspections of maintenance are made by personnel from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and from local levee and drainage districts, in this case the Rankin Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District, also known locally as the Levee Board. This board has been given broad powers to deal with flood control along the Pearl River in Rankin and Hinds Counties. The board is made up of the mayors of Richland, Pearl, Jackson and Flowood as well as the head of the Mississippi Development Authority, Leland Speed, in his role as representative of the Mississippi State Fair Commission. Robert Stockett Jr. represents Hinds County, and the chair, Billy Orr, represents Rankin County. The board itself is funded by the Boards of Supervisors of Rankin and Hinds Counties.

There are fourteen miles of levees in the Jackson area that protect flood lands in Flowood, practically all of Pearl and those in Richland. They also protect those lands below the bluff around the fairgrounds on the Hinds County side of the river. The levee board has taxing power on property that is protected by the levees. If you own a business or property that is protected by a levee, then you are taxed by the Board to help pay for the maintenance of the levees as well as pump maintenance and levee patrols during flood times. The tax revenue brought in by the Board totals less than a half million dollars. The Corps and the Levee Board have agreed to initiate a three-year, $2.8 million feasibility study that will be limited to updating the cost of the 1996 levee plan and a complete analysis of the LeFleur Lakes Plan. “We don’t have a set schedule for reviewing the progress of the analysis,” Orr said, “We have other things to do, but the Corps will be on it daily and we’ll keep up with it very often. We do keep up to date on it, and it is our responsibility to make sure it goes right. Whatever the requirements are as these studies go along, we will meet as often as necessary.” Orr said that they follow the Corps’s recommendations in matters of maintaining the levees and that while some people might claim that they are more partial to one flood control plan over the other, “We will be partial to LeFleur Lakes only when it has been studied and it has been proven that it can do the job.”

The decision to put the LeFleur Lakes Plan in the hands of the Levee Board was made by the three county governments of Rankin, Hinds and Madison Counties as well as the governing bodies of eleven cities in the three county areas. Purportedly, they will expand the district and build some version of the project. The levees will be incorporated into the LeFleur Lakes strategy, since the levees were part of the original “Two Lakes” plan. According to Gary Walker, project manager for the Corps of Engineers, “The EIS (environment impact statement) draft (for LeFleur Lakes) is scheduled for October, 2005 and it will take about six months after that for the final. The recommendation will be a joint process between us and the sponsor,” Walker said. “It will be a plan we both can agree on, it will be a joint recommendation between us and the Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District. We’re doing a full evaluation and the study will determine how we assess the project. We’re not going to make any pre-determined notions. The study will speak for itself.”

As to alternatives to LeFleur Lakes and the comprehensive levee plans, no others are under consideration, since Walker said that the Corps can’t recommend anything without a sponsor. But “assuming we went through the process and found a feasible plan and a sponsor, yes, we could approve (an alternative).”

“People ask how long it will be before a flood control plan will be put into place,” Orr said. “But we don’t know how long it will take. The study itself is going to take two and a half years. After that, it would be left up to funds that are available, and this project (LeFleur Lakes) is big. Now, it might not come to anything, because environmental concerns might knock it down or something else like public sentiment or lack of funding might come into play. The only thing I can say is that this board would like for the LeFleur Lakes project to be a reality if it does the job in controlling flooding. The only thing we’re interested in is flooding. Economic development and all the other factors do not interest us. Our job is flood control, and if this project does not meet the required specifications, it will be gone. I’m sure there’s room for modification,” Orr said. “With all the study and money going into this, we hope something will come out of it that will work. The only thing for sure is that Rankin and Hinds Counties need some flood control assistance somewhere. I was head of the Fair Commission in 1979 during the Easter Flood and we lost over $2.5 million, and that’s a lot of money.”

* * * * * * * * * *

In the final analysis, until people begin to perceive of the Pearl as a resource rather than as an obstacle, LeFleur Lakes, or some similar project involving development along the river that will control flooding and perhaps create revenue, will continue to receive a lot of support in the Jackson Metro area. But we do have other choices. Metro Jackson can either preserve the riverfront with options that have the potential to appeal to a younger, more aggressive entrepreneurial population while continuing to promote more downtown development, or the city can align itself with political and business leaders who seek to develop the riverfront at great expense and create a new district that will in all likelihood fail within the next decade or so, benefiting nobody save those who developed (or dredged up) the property in the first place. Supporters say the LeFleur Lakes idea is just a different approach from the levees, one which has the economic development and recreational components that levees just don’t have. They also cite the support of local governments, state agencies and the congressional delegation. John McGowan, the Jackson entrepreneur who originally conceived of the LeFleur Lakes (then called Two Lakes) plan, declined to comment on the evaluation in a telephone interview and deferred comments on the project to the Levee Board.

Detractors of LeFleur Lakes tend to focus on the negative environmental impact the project will have, but not necessarily in the sense that it will endanger already threatened species of wildlife. These detractors cite numerous studies showing that in addition to education and other quality-of-life issues, aesthetics and recreation are important to young entrepreneurs, especially younger business owners who are looking to relocate. They point out that LeFleur Lakes is going to destroy the wetlands and natural resources that are in the corridor, the same resources that in other parts of the country, smaller urban areas use to provide green space for recreational opportunities that appeal to people oriented towards activities carried out in natural settings, like hiking, biking, jogging and nature viewing.

These critics feel that the LeFleur Lakes project is simply not progressive enough and does not address the changing demographics and mindset of the 21st century South. In this context, the controversy surrounding LeFleur Lakes becomes a conflict of perception about the way Jackson should move, about the best venues that the city can take in order to become a more vibrant community rather than a battle between tree cutters and tree huggers. As an alternative to both LeFleur Lakes and the comprehensive levee system (which unlike LeFleur Lakes included green space facilities), proponents of green space, who include local businessmen as well as conservationists, are proposing a greenway that will transform what is now a denuded floodplain into an area that will feature hiking, biking and jogging trails, parks with sports fields and playgrounds, a scenic river corridor for boating as well as wilderness areas. Jackson geologist Dan Hill is among those who maintain that the greenway proposal has the potential to increase city revenue by attracting young professionals and entrepreneurs who look for such things as aesthetics and outdoor recreational activities when seeking to relocate. “The Levee Board has denuded the area between the levees to improve the convenience of the flood waters out of the flood zone,” Hill said. “The Levee Board maintains the levees and the floodways such as the areas at Lakeland and I-20. They clear the floodways rather than do any aesthetic features and it’s ugly.”

“When you clear the trees away from the river, there are no roots to hold the banks,” Hill said. “The reason they clear the trees is that those trees and vegetation create a drag on the water going through, so what they do is straighten up and dredge the channel as it has been along I-55. That improves the passage of water. One of the things that the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks didn’t like was the clearings in the 1996 plan, which would have increased the number of clearings. It’s ugly; it looks like a moonscape going across I-20. And this creates a negative impression about Jackson.”

The greenway proposal is problematic because it can’t control flooding along the river and has limited appeal for those who are unaccustomed to more nature-oriented forms of activity (biking, hiking, kayaking, etc.) and are more acclimated to the hustle and bustle of a more people-oriented environment; shopping malls, for instance. But the environmental issues are still crucial. Water quality is a primary concern. According to Jackson businessman Jerry Litton, “If you look at the area that will be draining into LeFleur Lakes and look at the trash and debris that flushes from the city every time we have a rain, that is what the water in those lakes is going to look like.”

“Debris will collect on the edges of the lake, or collect on drifts that are out in the open or on the edges of the (proposed) island,” Litton said. “It’s going to be there, and somebody’s going to have to float around in a boat in a net and dredge it out, all of the stuff that comes down from the spillway itself, plus what flushes out of the creeks in the city.” Nonpoint pollution is also a consideration. Nonpoint pollution is source pollution, or “polluted runoff,” created when rain, irrigation and other water sources run over the land, picking up pollutants and transporting them to local water bodies. You’re going to hold water there in a large volume, and you’re going to have all the nonpoint pollutants that come from the city. Nonpoint sources are parking lots and roadways and fields. Then what about all the motor oil, paint and paint thinners that people won’t take the time to take to the toxic waste centers? It’s being poured down storm drains.”

Hill agrees. “The shallowness of the proposed reservoirs (LeFleur Lakes) is such that water temperature is going to heat up and that’s going to affect water quality. Not only that, but when they impound the lake they’re going to flood one landfill that I know of, and there’s probably a second landfill. I found out when they tore down the old Baptist hospital, they put the asbestos from that in a fill that would be flooded.” Sewer mains are another concern for the LeFleur Lakes project. Broken sewer mains would flow directly into the lake from the city. One such sewer is the West Main Intercept, which drains north Jackson and travels through the floodway. The construction of a lake in the floodplain opposite Jackson would put that sewer main underneath the lake itself. Environmental issues aside, when it comes to local sentiment, the LeFleur Lakes proposal appeals to a genuine need for the people of Jackson to feel as if they are living in a vibrant, growing community that is making changes and improvements. In addition to the attractions of proposed flood control and potential economic benefits, LeFleur Lakes has come to represent an alternative to apparently ineffective downtown development. Granted, LeFleur Lakes appeals more to the outlying metro area than it does to the city itself; on the surface, the project has much greater appeal for those sections of Ridgeland, Hinds and Rankin Counties between the spillway and Byram, but it still has its supporters in the city itself, not the least of which is former Jackson mayor Harvey Johnson Jr.

“The continuing flooding we experience nearly every year undeniably demonstrates that we very much need a comprehensive flood protection plan,” Johnson said. “As a member of the Rankin-Hinds Levee Board, I work closely with mayors from Rankin County and other board members to address ongoing flood control measures.”

“The public has rallied around the LeFleur Lakes project as an alternative to levees. The City of Jackson has gone on record as being in support of the LeFleur Lakes project, and we continue to work closely with federal, state and other local authorities to come up with the right answer to solve our problems with floods. We will continue to evaluate the LeFleur Lakes proposal as it evolves while we decide the best ways to provide flood control,” Johnson added.

But according to Matthew Dalbey, assistant professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at Jackson State University, “From a physical planning point or perspective, when you have an interstate between a new development project and downtown, I don’t see how that is going to help downtown. As a matter of fact, I think it’s going to make downtown dead. It’s just too big of a separation; it’s just like any other type of leap-frog development or urban sprawl. The people who argue for this will say that any new development within the boundaries of the city will provide a positive economic impact, but the issue remains that the new development will be separate from the old development. It will kill downtown because of the separation. I think that there’s a tendency to support new development by local people, so for instance you can get a premium rate for something new whether it’s strategically located or not. In other words, there’s nothing new downtown, so people aren’t investing downtown, but take the Fondren Corner building; it’s a redone building in an area that had formerly been in decline,” Dalbey said. “But the new investment in that place has been such that they can get a premium on the rents there. As a matter of fact, Fondren is in a rebound, and people like being there.”

Of course, it’s questionable whether LeFleur Lakes, or any such new development district will improve the local economy. Some people are of the opinion that the city has extended itself already and that further development is superfluous; after all, the state economy is drawing back, consolidating itself and trimming edges, so it makes sense that the capital city should follow suit. Under scrutiny, LeFleur Lakes appears to be an antiquated development concept that creates more problems both in Jackson and downstream than it solves. Jackson deserves a solution to flooding that is effective and progressive, one that focuses on enduring issues rather than quick-fix alternatives. We need protect ourselves, but we need to take care of our river, too; after all, she’s why we’re here in the first place.