The Lost Art of Farish Street

What fire of mind or heart feeds the human impulse to mold or mark the fabric and surfaces of the world into a semblance of imagined beauty? We cannot say; it is an indefinable spark, we can but marvel of its being.

These images were captured in 2004, and the work itself couldn’t have been very much over perhaps two years old. As to who painted them, I have no clue. Some seem to be by the same hand or set of hands, others don’t. When I first saw them on a lonely New Year’s morning, they brought to life that sad, lonely street.

A Farish Street Financial Timeline

| DATE | AMOUNT ($) | SOURCE | PURPOSE |

| 1 | 10/9/81 | 200,000 | CDBG* | Revitalization study |

| 2 | “ | 34,000 | CDBG | Extension of study |

| 3 | 7/23/82 | 100,000 | Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities via JSU | Historical survey of Farish Street |

| 4 | 12/10/89 | 1,600,000 | CDBG | Infrastructure, business loans, housing |

| 5 | “ | 85,000 | CDBG | Farish Street park |

| 6 | 11/22/94 | 50,000 | Jackson/Hinds Co. | Mary Means (Means Consulting) |

| 7 | 11/22/95 | 1,500,000 | State of Ms. | Alamo renovation |

| 8 | 3/7/96 | 130,000 | National Trust for Historic Preservation/State of Ms. | Renovation of Scott Ford House |

| 9 | “ | 200,000 | “ | Acquisition of property in Farish St. district |

| 10 | 3/26/98 | 2,500,000 | National Equity Fund; $600,000 from local banks; $350,000, CDBG (city) | “Rehab” of 37 historic houses |

| 11 | 4/27/99 | 6,000,000 | State of Ms. | Farish St. revitalization |

| 12 | 4/27/99 | 6,000,000 | Fannie Mae | Farish St. revitalization (matching of state funds |

| 13 | 3/23/01 | 1,500,000 | HUD? | Infrastructure |

| 14 | 5/22/01 | 900,000 | City of Jackson water and sewer fund | Infrastructure |

| 15 | 1/12/02 | 74,000 | ($50,000 J. Paul Getty Trust; $12,500 Ms. Dept. Archives and History; $3,500 Gannett, Inc.; $8,000 ChemFirst, Inc.) | Farish St./Scott-Ford Museum |

| 16 | 3/8/11 | 210,000 | Civil rights grant(?) | Medgar Evers House Museum |

| TOTAL | 21,082,000 |

*(Community Development Block Grant – HUD)

Not included in this document are amounts for donations of real estate (e.g.: from state of Mississippi; donation of Alamo from Sunburst Bank), funding for the Smith-Robertson Museum and contract fees paid to Performa Entertainment and subsequent developers.

1) Hester, Lea Ann. “City expected to extend study of Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger 19 October 1981: 1B. Print.

2) Ibid.

3) Hester, Lea Ann. “Farish: Older than thought?” The Clarion-Ledger 23 July 1801: 1B. Print.

4) Scruggs, Afi-Odelia E. “Development plan fails to revitalize Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger 10 December 1989: 1A. Print.

5) Ibid.

6) Simmons, Grace. “Farish Street consultants to share info.” The Clarion-Ledger 9 October 1993: (no page cited)

7) Gates, Jimmie. “Renovation closer for Farish Street’s Alamo Theatre.” The Clarion-Ledger 22 November 1995: (no page cited)

8) Harris, Barbara. The Jackson Advocate. “Farish Street Historic District gets infusion of national, state funding.” 7 March 1996: 1A. Print.

9) Ibid.

10) Fleming, Eric. “Farish Street renovation under way.” The Mississippi Link. 26 March 1998. 1A: Print.

11) Henderson, Monique H. “Draft document targets Farish St. Historic District:12M allotted for development of district.” The Clarion-Ledger. 27 April 1999. 1B Print.

12) Ibid.

13) Mayer, Greg. “$1.5M grant going to Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger. 22 March 2001. 1B: Print.

14) Ibid.

15) _______. “Black museum receives grant.” The Picayune Item. 12 January 2000. (no page cited)

16) Mitchell, Jerry. “$2M-plus in grants awarded to state civil rights sites.” (“$210,000 will help stabilize the foundation and repair the Medgar Evers House Museum in Jackson.”) The Clarion-Ledger. 3 August 2011. (no page cited)

Cuties on Farish

The Palace Auditorium on Farish

Farish Orange

Farish Street

Blue Man on Farish

My Neighbor Wil

Wil lived around the corner from me in a sedate residential neighborhood in downtown Jackson, Mississippi. More than anyone I’ve ever known, Wil embodies the American Dream of work rewarded and a life well-lived. Here is his story for the world; it matters.

I was born September 26, 1939, in a shotgun house on Farish Street in the heart of the black community. The neighborhood had four barbers, three restaurants, and two fast food restaurants for hamburgers, pig ears, smoked sausage, and sandwiches. We had our own grocery store, a cleaner, a shoe repair shop, a laundry, an ice cream parlor, and movie houses on Farish and Amite. We also had two funeral parlors, a bike shop, and a bus company that brought people from the country to sell their produce. Three doors from my house was a pool hall and a cab stand, and all my friends lived within a few blocks.

My aunt always told me I should try to make some money on my own, so I got a job at a beauty parlor on Capitol Street. It was owned by a guy named Baldwin, one of the biggest jerks who ever lived. He said he’d give me six dollars a week to shine shoes, but I couldn’t take tips. I was supposed to make six dollars a week, but he would give me five one week and four the next.

It went on like that for a while until I finally got tired of it and told my aunt. She said, “We’re going to go down and get your money.” She put her pistol in her purse, and we went to the beauty parlor. “Mr. Baldwin,” said my aunt, “you owe this boy six dollars, and you need to pay him.” Baldwin said, “Well, I’m not going to give him anything. He’s fired.” My aunt reached into her purse and pulled out her pistol, walked around the chair where he was standing and said, “You need to pay him his money.” And he did.

Our house at 518 Farish backed up on an alley across from Rodger’s Tailor Shop. Up the alley lived a lady bootlegger named Cara Lee, whose daughter was a whore. All kinds of trouble went on up there on Friday and Saturday nights, and, because my bed was under a window, I heard things I hoped I’d never hear again. Sometimes the police raided Cara Lee’s place, and one night a policeman shot our little cocker spaniel just because he was barking. At that, my aunt came out of the house with a Winchester rifle and told the policeman she might blow his brains out. A long, tense moment passed, and I was sure someone was going to get shot, but finally another officer came over and said, “Please ma’am, Lord to God, he was wrong to shoot your dog, and I’m sorry.” The policeman apologized, and my aunt huffed back into the house.

After all that, my aunt decided it was time for me to get back with my mother. She said, “Son, you know I love you more than life, but if you stay here, either I’m going to be killed or you are. I think it’s time for you to go be with your parents.” Correspondence went back and forth, and in the summer of 1954, I left Jackson and went to Madison, Wisconsin, where my mother and stepfather rented a house in South Madison. The neighborhood was called “The Bush” and was made up entirely of blacks and Italians. I was surprised because every one got along fine.

My new school was Edgewood Sacred Heart Academy, where I was the sixth black among five hundred students. I didn’t do well in school; it was hard for me to concentrate because of the trouble I had at home. My stepfather was an alcoholic, and he couldn’t stand to see my mother and I growing close.

In 1958, I graduated from Edgewood with a C-minus average. Luckily, I was a good athlete and got an offer from Bishop College in Marshall, Texas. I played ball for them over a few semesters, when, out of the blue, my real father sent me a train ticket to come out to Los Angeles. I liked being with my father and planned to go to L.A. City College in the fall, but my grandmother died, and my mother insisted I come back to Farish Street for the funeral. My father begged me not to go, but I had to. I never saw my father again.

By 1961, I was living in Madison again. One snowy day, I was walking down Park Boulevard when two of my buddies and a woman drove by in a Volkswagen bug. I asked, “Where are you going?” They said, “We’re going to New York City.” I said, “Hold on, drive by the house, let me pick up some stuff!” That’s how I got to New York.

I’ll never forget standing on 6th Avenue thinking, “I’m in New York! I’m in the Village!” I moved into a little flea-bag hotel on 43rd Street and found a part-time job right around the corner. Everything was fine until I started going out with a woman who worked in the same place. It wasn’t long before our relationship got to a point where I felt trapped. I wanted to be free, but didn’t know what to do.

One morning, I was looking at the travel section of The New York Times when something caught my eye: a Yugoslavian freighter was due to sail out of Brooklyn for Tangier and Morocco, and you could get passage for $141. As soon as I saw that notice, I remembered the night back in L.A. when my father shook me awake. I said, “What’s the matter?” He said, “Dorothy’s in the kitchen.” I said, “So what?” He said, “She’s boiling water to make tea, and she don’t drink tea. Get dressed–we’re going to your sister’s.”

That was it. If you want to get free, all you have to do is leave. A few days later, I was on that Yugoslavian freighter bound for the Straits of Gibraltar.

The voyage lasted nine days. I had my own room, the food was excellent, and I got so drunk off slivovitz, I’ll never drink another drop of it. When I got off the boat in Morocco, a little Berber kid offered to carry my luggage. Now, I’d just gotten off the boat from New York, where you do NOT give someone your luggage. When I hesitated, the kid looked at me an said, “What’s wrong with you, black man? You’re home now!”

In Tangiers, I rented a room for seventy-five cents a day in a hotel near the Casbah. A few days later, I went to an American bar and was introduced to Mark Gilbey, who owned Gilbey’s Gin. We talked and had some drinks, and after a while, he invited me to a Christmas party. He had a fabulous place overlooking the Atlantic Ocean with a red room, a blue room, and so on.

I stayed in Morocco nine months, in Tangier, Affairs, Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakesh, and Showan. When I finally decided to leave, I crossed the Mediterranean to Spain. I loved the Spanish people, but when I got into France, I ran into problems. I didn’t speak French, and the natives were nasty about it. From Nice, I took a train into Rome. I was sitting on the Spanish Steps when a guy came up to me and said, “My name is Wilpert Bradley, I’m from Chicago, and I’m gay.” I shook his hand and said, “My name is Wil Cunningham, I’m from New York, and I’m straight.” He laughed and said, “Wil, you’re the first American I’ve met who didn’t take offense at that.” I said, “I’m travelling and living my life. Ain’t no problem.”

Bradley had come over with the “Cleopatra” film company. He had a big place over on Via Seccalle and let me a room in the back. That’s where I stayed for a year and a half.

I did a little modeling, and I was in some spaghetti Westerns, made up as a Mexican bandito. I got fifty dollars a day to stand around and wait for them to shoot me and fall off the horse. It was fun–fifty dollars a day for doing nothing. When I’d made a little money, I’d go up in the Scandinavian countries. I just travelled, met people, travelling was cheap, I could get on the train and be in Paris in just a few hours. But Rome was my home. I could go away for four or five days and come back, and I had a place to stay.

Some friends were showing my Portfolio around to movie companies in Rome when my mother called with bad news. My step father was in the hospital with cirrhosis of the liver, and the doctors feared he would not make it. I thought it was time I should go home for a while–I could get back to Europe after the crisis was over. As it turned out, it would be years before I returned.

When I got back to New York, I stayed with a friend from UW and waited for instructions from mama. The friend was from New Rochelle, New York; that week-end, there was a party up there, and he asked me if I would like to go. That was one of the best things that ever happened to me, for it was at that party I met my wife-to-be. We had a great time together, and we fell in love.

Her father gave us good advice: “Get out of the city,” he told us. “Get out of New York. You’ll never make it there.” My stepfather was in a Madison hospital, and my mother was having a hard time. I talked it over with Beverly, and she said, “Let’s do it. Let’s go to Wisconsin.”

I fought my demons and finally reconciled with my stepfather. As for Bev, my mother thought of her as a daughter until the day mama died. Eventually, Bev and I found jobs, and in no time, we had our own place. That September, we went back to New York and got married.

I attended community college to see if I could get my grade average high enough that a university would accept me. Meanwhile, I got a job at a clothing store called “No Hassle.” The guy liked me a lot because I was very fashion-oriented, I had just come back from Rome, and I knew a lot about clothes and shoes. What I really wanted, though, was to open my own business.

After a year at the community college, I qualified to enroll at the University of Wisconsin, but the desire to open my own business was too strong, and I only stayed one semester. I reached out to a friend of mine, Lamont Jones from Mobile, Alabama, who had just gotten his MBA, and we wrote up a business plan for a woman’s shoe store. He would handle the money, and I would be the buyer, something my time at “No Hassle” had prepared me for.

After five years, Lamont and I realized we had a losing proposition. We just couldn’t get ahead, and we still owed Small Business nine thousand dollars. We went down there to pay them off, and the guy said, “We can’t take cash.” I said, “You’re going to take cash today, and I want a receipt.” I counted out nine one-hundred-dollar bills, then Lamont and I split up the remainder: two thousand dollars each, same as we started with.

I decided I’d have to set aside my father-in-law’s advice and return to New York. I had contacts among shoe buyers and suppliers, and through them, I met the general manager of Thayer-McNeil, a division of Florsheim Shoes, in Manhattan. He made me manager of a store at 73rd Street and 3rd Avenue. I had been at Thayer-McNeil/Florsheim a year when a guy told me about a job with Converse. At that time, Converse had an office on the eighty-first floor of the Empire State Building. As soon as I walked in the door, the general manager said, “You’re hired. I like the way you walked in.” (I always dressed well as a salesman.) When the paperwork was finished, I was told my territory would be Brooklyn, a part of New York I knew nothing about.

They gave me a company car with a trunk-load of samples. Next day, the valet parked it in the garage while I went up to the eighty-first floor to check with the general manager. When I got to the car again, I drove across the Brooklyn Bridge and down Flatbush Avenue to my accounts. My first stop was a store that sold Converse; I went in and gave the manager my card. Luckily, business was slow, and the manager was glad to have someone to talk to. I went out to the car to get my samples from the trunk . . . and they were gone! I drove straight back to Manhattan, had the valet park my car, went up eighty-one stories, and said to the general manager, “Irving! I went to a store on Flatbush Avenue, went in to see the manager, came out to get my samples–and they were gone!” Irving closed his eyes for a moment, then said, “Earlier this morning, you parked in the garage downstairs, right?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Next time, when you give the valet your keys, take the trunk key off the ring.” That was my first lesson on the new job.

Irving Cole taught me a lot when I was at Converse. My first time out with him, for example, he taught me to listen. We went into a store in Brooklyn, and before I could unpack my bags, the store manager started complaining about how hard it was to work with our company. He went on for a long time, using language that made me uncomfortable. Meanwhile, Irving never said a word, just let the guy vent. Finally, when the manager calmed down a little, Irving said “Let me apologize for the problem you have getting this shoe in your store.” Then he took out a notepad and asked what colors and sizes the guy needed, and how soon he would need them. When he had the information, he went to the store phone, called our customer service, and arranged for everything to be shipped next day.

After we left the store, Irving asked, “What were you thinking in there?” I told him the guy scared me, and if I’d been by myself, I probably would have walked out. “You got to listen,” Irving said. “The whole time we were in there, the guy never once said he didn’t want our product–he was mad because he couldn’t get it when he needed it. The secret to making a sale like that is not to overreact, but listen to what the guy really needs and see that he gets it. The most important thing you can do is listen.”

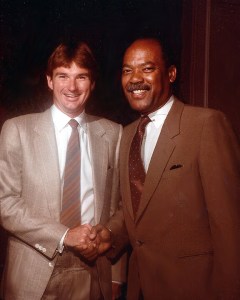

In November, 1975, I moved to the sporting goods division, which is where I should have been in the first place. My territory was all five boroughs of New York City. It was a ten-million-dollar account, and I made that and above. In addition, I was given the responsibility of signing pro athletes for Converse; I had the Jets, the Giants, the Knicks, the Jets, and the Yankees (I would go to spring training with the Yankees and make sure they had everything they needed.) Famous guys like Reggie Jackson, Larry Bird, Bernard King, and Larry Johnson would call me at home. Yogi Berra called once, and Spring, my youngest daughter, said, “Yogi the Bear is on the phone!”

I worked that job for twenty-nine years, trying to make a difference. Then, in 2000, I made up my mind that Converse was going nowhere. New owners were taking over, and they were looking to flip the company to the highest bidder. I knew I was not part of their plan, so I took my retirement. It was all right with Bev; she knew it was time.

After my stepfather died in 1996, my mother went home to Jackson, and I talked to Bev about moving down there to look after her. Bev was all for it; she loved mama and was like a daughter to her. We owned five acres in Madison County, and I had the dream of building a big house where all of us could live. In 2001, we moved south, back to the town I started out in. Before long, I realized my dream of building a big house in the country was not going to happen. First, every contractor we spoke to quoted a price way out of our range. Second, I discovered that, no matter how much two women might love each other, each wants her own place.

Bev and I ended up buying a beautiful little house on Kenwood Street in Belhaven. The neighborhood is old and peaceful, and I looked forward to reconnecting with people I’d known as a teenager. As it turned out, this was another dream that, if not lost, was deferred.

One day I brought my oldest friend to the house we had bought. When we got out of the car, I noticed he was hanging back a little, as if he were confused. “Why did you buy a house here?” he asked. “We never came over here when we were kids. Who do you know lives here?” I said, “I was told there’s only one other black owns a house in Belhaven. Now there’s two.” He had nothing to say after that. Another time, Bev and I invited about ten people over for coffee. The men were uncomfortable, and the women sat with their purses in their laps and said little or nothing. These people will always be friends of ours, and we hope that, one day, whatever discomfort they felt will be a thing of the past.

Farish Street is empty now; all the life is washed out of it, and it will never again be like it was when I was a kid. We can’t return to the past, and often it’s hard to catch up to the present, yet, after eighty years, I find myself looking down the road to bridges I’d like to cross. All I can say now is what I said to Wilpert Bradley on the Spanish Steps so many years ago: “I’m travelling and living my life. Ain’t no problem.”

Interview with Helen Ackle Lyons

The Lebanese community is a pillar of Jackson society, well deserving of a more comprehensive look, but this interview with Helen stands superbly on its own.

I’m first-born in this country.

My grandfather’s brother married my daddy’s sister (Ellis Joseph and Albert Joseph). Albert was married to Mary Ackle, the English spelling they gave us in Ellis Island. Other people with the background name, which means “brain” in (Levantine Arabic), spell it “Akl”. The Cherokee Inn founder was my daddy’s brother, Joseph Ackle. The other side of the family “Aswic” (?) but they took Christian names. “Aswic” in Arabic means “black”, but the name they took was Simon. And that leads to another story; that of why they used the name “Simon”, which is of course in the Bible, as were all the names: my brother was Isaac, his brother was Joseph (Ackle).

The Simon surname comes from my mother’s uncle; he first came to this country sometime around 1900, earlier than my (Ackle) family. They came through New York. All the families I’m talking about came through Ellis Island. When the Lebanese people all have a name that maybe they spell a little different, “Ackle” can even come from the name “Hackle”. They took these names because of the pronunciation. It wasn’t clear, what with their “brogue” their accent, whatever you want to call it, some would put an “h” on it because of the guttural pronunciation. I know more because of my grandmother, my Daddy’s mother, she lived with us in Jackson. They first came to Lawrence, Massachusetts, which is a bedroom community of Boston. And the reason for that was, so many of the ethnic people stayed there in Lawrence. So many of the cemeteries are full of the Orthodox families who lived there. And one of the Joseph boys, who was Albert Joseph’s grandson, that’s my Daddy’s side of the family, they were Ackles on that side, on the Albert Joseph side. The Ellis Joseph side, though they were brothers, I was not directly kin to them, however, all of these people in Lebanon came from the eastern side of Beirut, up in the mountains.

We spoke Arabic, but not the “true Arabic”. When they came to this country and wound up down here, there was not an Orthodox church here in Jackson. The first Greek Orthodox church in Jackson did not appear until during the Forties. At that time, if you wanted to go to an orthodox church, at that time the orthodox church in Vicksburg was one of if not the oldest in the Southeast. The Lebanese people came to Vicksburg earlier than ours did to Jackson. Ellis Boudron’s family was one of the earliest Lebanese families in the country. Mary Louise Jones is my second cousin. Her daddy was my first. William P. Joseph was my daddy’s nephew. I went with my cousin William P. Joseph to Lebanon. I promised my mother’s mother, Haifa Nassah, married a Simon, original name was Aswic. The reason they became Simon is because my grandfather’s half-brother, who was a professor at the University of Beirut, came to America before the rest of them. He became a professor at the University of South Carolina.

I went to kindergarten at Poindexter. It was the only school that had a kindergarten. We moved from Farish Street to Gallatin Street and then to west Jackson when I was six years old. Clairmont Street. I was born in 1925 so that would have been in 1931. The street is no longer there. I went to Barr School. I went to Enochs Junior High, then to Central High School. I graduated in 1943. I want the emphasis on the culture. People seem to think that I’ve had a very interesting life. I married in New York City, a story that started in WWII. I can’t say that any of my other cousins had the kind of life that I had. My husband was from Pennsylvania. The only reason I was permitted to get married at that time was that my father was interested in the military because he got his citizenship by serving in the military in New York City. My father was interested in going back to Europe because when he came to this country, he left from Le Harve, France. Believe it or not, he was in the air corps in WWI he delivered mail on a motorcycle to the troops in France. That was the story my Daddy told. And he knew some French because of the French in Lebanon. When he came to America, he came because they were being starved. There was a famine, and my father remembered it. I listened to the old folks with my ear to the doors. They spoke in Lebanese among themselves.

Over the years, we have learned many things through our federation that we did not know, these things that we are learning how our culture relates to the Jewish culture. The Federation of Southern Lebanese Clubs has been in existence for about eighty years and has been a life-saver for so many people in our culture to learn from the professors that have studied our background, particularly the ones at the University of Texas. The immigrants didn’t want any emphasis put on them being Lebanese; my father hid a lot of things from us when we were children; he wanted us to grow up as Americans, and we did. He was a young man when he came to Jackson, around 10 years old. He was born in 1898 (Isaac Ackle).

Getting back to them coming to this country, they stayed in Lawrence, MA, until his mother, my grandmother and my daddy went back to Lebanon to get the youngest child who couldn’t come in on the first passage that they bought on a family passage. The little girl was younger than my daddy. I’m assuming, since he was like 10 when he did that, it must have taken them two years to go there, come back and then come South. I know that there were many Lebanese scattered in this area already. It was less developed than in the north, and they were out to make a livelihood out of what they did in the old country. They were merchants and during those days my grandfather peddled, wheeling a buggy, peddled merchandise, “notions”, Momma’s side was related to S.N. Thomas. But they all knew each other. They all came from small towns: Dufaya, Duschway, we have maps showing where they came from. They’re at the clubhouse on Cedars of Lebanon. The building has been there since I was 13. It was dedicated in 1938, July.

My grandfather Joseph Ackles was a peddler. He got to the neighboring communities in a cart with a horse. That year was probably like 1910-11. He peddled materials, dry goods, and there was a family in Jackson whose family wrote a book about Mr. S.N. Thomas, very well-known, they had a wholesale business on President Street. My mother’s mother was related to that family (you can use Billy “William” Thomas as a reference; he still doing ordering for merchants, and he is the surviving grandson of S.N. Thomas). This leads to the Buttross family in Canton.

Let me go back to the clubhouse. The reason we have a clubhouse is because we did not have a church and they wanted to keep the culture alive for their children. That was the reason for five brothers, five names that started the club by buying fourteen/twelve acres. The brothers were the Ackle brothers, two of them, Isaac and Joseph; the Sik brothers; the Joseph brothers, the Simon brothers; I don’t know who the fifth brothers were. Alfred Katool could tell you the fifth. The clubhouse was built by the WPA. And the governor of Mississippi, Hugh White, dedicated the club.