Farish: Jackson’s Dead End Street

After over forty years and $25 million, the prospect of transforming Farish Street into an urban oasis of bright lights, great food and memorable music has lost its luster.

In January 1980, a month before Farish Street was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the city of Jackson launched plans to revive the area by making a contract with the National Business League for a $200,000 revitalization study. The contract as well as the cost of its extension a year later (an additional $34,000), was paid out of a Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The result of this study was the city’s ambitious 1984 Farish Street Revitalization Plan, which proposed to restore commercial and cultural activity in the district by enforcing codes, upgrading the infrastructure, improving housing and constructing a park between Farish and Mill streets. These improvements were to take place over a five-year period, but by 1989, the effort had failed; businesses had not moved into the area, crime was rampant and what housing existed was substandard.

But the revitalization of Farish Street retained its glamour, and in 1999, by far the largest infusion of money came from the State of Mississippi and Fannie Mae, $6 million from each. This money went to upgrade the infrastructure of the historic district, which began in 2002, the same year the city signed a contract with Performa Real Estate to develop the area at an estimated cost of $20 million. Six years later, Performa left the city after a bitter imbroglio with Mayor Frank Melton.

*(Community Development Block Grant – HUD)

(Not included in this document are amounts for donations of real estate (e.g.: from state of Mississippi; donation of Alamo from Sunburst Bank), funding for the Smith-Robertson Museum and contract fees paid to Performa Entertainment and subsequent developers, among other costs.)

1) Hester, Lea Ann. “City expected to extend study of Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger 19 October 1981: 1B. Print.

2) Ibid.

3) Hester, Lea Ann. “Farish: Older than thought?” The Clarion-Ledger 23 July 1801: 1B. Print.

4) Scruggs, Afi-Odelia E. “Development plan fails to revitalize Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger 10 December 1989: 1A. Print.

5) Ibid.

6) Simmons, Grace. “Farish Street consultants to share info.” The Clarion-Ledger 9 October 1993: (no page cited)

7) Gates, Jimmie. “Renovation closer for Farish Street’s Alamo Theatre.” The Clarion-Ledger 22 November 1995: (no page cited)

8) Harris, Barbara. The Jackson Advocate. “Farish Street Historic District gets infusion of national, state funding.” 7 March 1996: 1A. Print.

9) Ibid.

10) Fleming, Eric. “Farish Street renovation under way.” The Mississippi Link. 26 March 1998. 1A: Print.

11) Henderson, Monique H. “Draft document targets Farish St. Historic District:12M allotted for development of district.” The Clarion-Ledger. 27 April 1999. 1B Print.

12) Ibid.

13) Mayer, Greg. “$1.5M grant going to Farish Street.” The Clarion-Ledger. 22 March 2001. 1B: Print.

14) Ibid.

15) _______. “Black museum receives grant.” The Picayune Item. 12 January 2000. (no page cited)

16) Mitchell, Jerry. “$2M-plus in grants awarded to state civil rights sites.” (“$210,000 will help stabilize the foundation and repair the Medgar Evers House Museum in Jackson.”) The Clarion-Ledger. 3 August 2011. (no page cited)

Prospective investors have been discouraged by the unaccountability of financed development in the area, particularly by the Farish Street Historic District Neighborhood Foundation, the steering organization for the revitalization project, which was founded in 1980, moved to the Office of City Planning in 1995 and disappeared (along with its documentation) in 2006. The ensuing decade brought diminishing appeals for Farish revitalization, and in 2015, Mayor Tony Yarber, faced with what was to become a chronic city-wide breakdown of essential infrastructure, stated in 2015 that the project was “on the back burner”.

Once considered the keystone project towards the revitalization of decaying downtown Jackson, Farish Street has instead become a byword for boondoggle and corruption as well as a forlorn Potemkin village in the heart of the city.

Red Sweeper

Farish Orange

Magnolia Door 3

Duke and Fats

Blue Man on Farrish

Hands on Farish 3

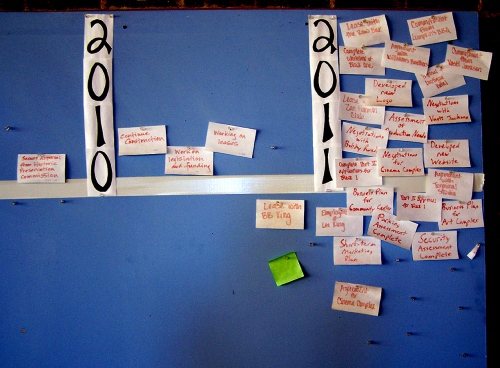

A Farish Street Timeline

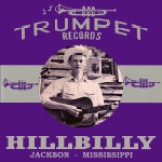

Saving Trumpet Records

309 Farish Street, the home of Trumpet Records, is a ruin.

The impact of Trumpet Records on American music has been profound and lasting, but the site of the studio is rapidly decaying. The building that housed this jewel in the crown of Mississippi music has not only lost its luster, but it’s become a dilapidated shell. While the roof and walls are intact, they’re barren and pitted, covered with patches of peeling paint and without windows, open to the erosive elements of weather.

Musician Sherman Lee Dillon is the driving force behind a group of people who seek to preserve and restore the building with an eye to commemorating Trumpet Records and its music. “What we’re trying to do is ensure that the old building where these legends laid down some the most famous tracks in Mississippi music is preserved. Maybe we can even to get some momentum going towards the restoration of Farish Street itself.”

Dillon notes that the 30-year efforts to restore the Farish Street District by massive infusions of public funding have stalled. “We think it’s worthwhile to give private initiative a chance.”

To that end, Dillon and his group have secured a lease on 309 North Farish Street, one of the few privately-owned properties in the Farish Street Historical District. Dillon said that he asked the owners not to lease or sell 309 Farish until he had an opportunity to restore it.

“They have stuck to their word for three years and not seriously entertained any other offers,” he said. “But I have not been able to find any pockets to get money from, and I am in not in a situation for matching funds. The city does nothing to support the project, even though the mayor drops by from time to time. I can’t wait any longer. If I can’t get the money to restore it, Trumpet Records goes on the block.”

Dillon said that once the building is secured, he will work on creating a nonprofit business, a museum and a recording studio. “I am personal friends with musicians who have played with several Mississippi blues people, Johnny Taylor, Milton, Bobby Rush, Dorothy Moore, BB King and Albert King.” Dillon points out that while Trumpet had some national recognition, their recordings of local celebrities might be one of the most interesting aspects of the proposed museum.

“The problem is that there’s no money for restoration,” Dillon said. “The agreement I have with the owners is for two years’ rent, $48,000, paid in advance within 30 days. That money will be used exclusively for the restoration of 309. Any money that comes from the operation of 309 for the next two years will be to further the services of the restoration.

“All I can say is that if this doesn’t work, a golden opportunity has been missed.”

Details available at Save Trumpet Records