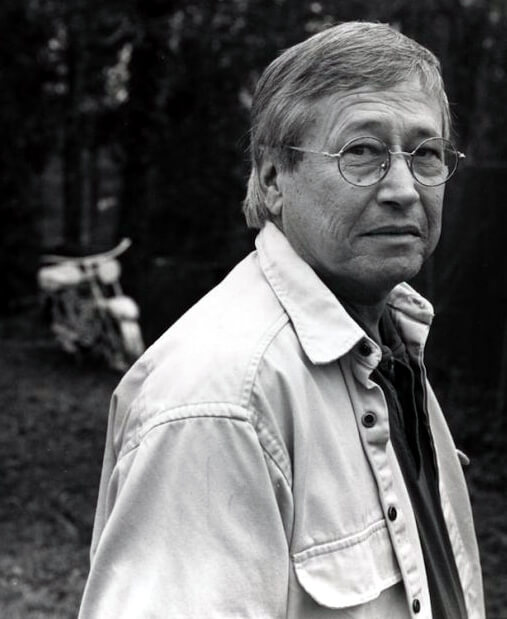

I took Barry’s first class at Ole Miss as an undergraduate.

The class was held in Bondurant East, second floor, overlooking the Williams Library. Donna Tartt was in the class as well, a very pretty young lady who turned in a wonderful short story about a woman held captive by a man whose passion was orchids. I turned in a brutal little story about a woman who had murdered her husband in front of her youngest child that Hannah found “just a little bit over the top, Yancy,” since the child later went on to commit suicide as an adult.

“Murder and suicide both in less than five pages?” he asked. He looked at me, shrugged and grinned.

Barry was drinking heavily at that time, and it wasn’t a week later before he showed up just as drunk as he could be. The entire class just sat in their seats, dumbfounded, as he rambled on about poetry, fiction and flying around the Gulf of Mexico shooting tequila with Jimmy Buffet. We were dismissed early.

My friend and classmate Robert Yarborough told me to stay after class and help him get Hannah home. I drove Barry’s car, Robert followed on his motorcycle. First stop was to a supermarket, where Barry gave me a wad of money and told me to buy a steak (“I need protein!”), then to the run-down duplex he shared with Robert on Johnson Avenue.

At the next class we were on pins and needles wondering if Hannah would show up, but of course he did, apologized, told us to forget about it and delivered one of the best lectures on the craft of writing I’ve ever heard before or since. “You’ve got to write, write, write” he said. “If you don’t use it, you’ll lose it.” Trite, I know, but when Barry said it with that raffish grin of his, he made it stick. He taught us to listen to ourselves, and that was a great gift.

Later on that semester, I was sitting in the Gin having a few beers and scribbling on a pad when Hannah walked in. I nodded a greeting, and eventually he ambled over and we started talking. He asked about the short story I’d written. I told him I’d gotten the title (“A Roof of Wind”) from Faulkner,, and for some reason this infuriated him. I got the impression that he was sick and tired having his mule and wagon stuck in the Dixie Limited wheelhouse. Not knowing what else to do, I apologized and left posthaste. He never brought it up again, and I certainly didn’t.

Like Morris, Hannah was subject to the fawning of fans, but while Willie reveled in holding late-night, dissolute salons where he was the center of the attentions of a cadre of hangers-on, Barry kept a somewhat lower profile and a more select company. I knew many people who traveled in those circles, and they enjoyed regaling those of us who weren’t members of said cliques with their second-hand wit and wisdom.

On reflection, it wasn’t a good time for either Morris or Hannah. Neither published anything of matter those years; Barry began bottoming out with Ray, while Willie was churning out even worse froth in the form of Terrains of the Heart. But unlike Morris, Hannah pulled out of it, wrote, and wrote well. He had to, and he did.

Hannah was the finest Southern writer of his generation, eye, ear, and voice. Oh, he was a bad boy to be sure; he had the witting arrogance to be vulgar when the situation presented itself and his snide insinuations peppered anything he wrote. Begrudge his digressions, but Hannah was a singer.