During the heyday of Prohibition, the speakeasy districts of New York and Chicago became dazzling gathering places, filled with music, dance, and drink–as well as a few bullets, mind you–as did similar areas in the South, notably Beale Street in Memphis and of course the French Quarter in New Orleans, which doesn’t shut down for a damned thing.

In Jackson, Mississippi, it was the Gold Coast. Also known as East Jackson or even “’cross the river”, the Gold Coast comprised the area of Rankin County directly over the Woodrow Wilson Bridge at the end of South Jefferson Street. Though barely two square miles, its infamy was nation-wide.

In 1939, H.L. Mencken’s The American Mercury, published a rollicking account of the Gold Coast, “Hooch and Homicide in Mississippi”, by Craddock Goins. “There is no coast except the hog-wallows of the river banks,” Goins wrote, “but plenty of gold courses those banks to the pockets of the most brazen clique of cutthroats and bootleggers that ever defied the law.”

Goins cites Pat Hudson as the first to see the possibilities of lucrative gambling near the junction of the two federal highways (Hwys. 80 and 49) across the river from Jackson where before then there were only gas stations, hot dog stands and liquor peddlers. Then San Seaney began selling branded liquor at his place, The Jeep, which soon became a headquarters for wholesale illegal booze.

Others sprang up like mushrooms. The sheriff of Rankin County did his best to restore some semblance of law, but as soon as he cleaned out one den of iniquity another opened. Not only that, he was severely beaten and hospitalized for two weeks after one raid, and he simply bided his time until his term ran out. Goins reported that whites and blacks were often together under the same roof then, albeit shooting craps and whiskey on the opposite sides of a thin partition.

This lawlessness did not pass unnoticed in the nearby state capitol. Governor Hugh White, who in December of 1936 ordered National Guard troops into a business on the Pearl owned by one Guysell McPhail. Liquor was seized as evidence that the place should be shut down, but a Rankin County chancellor later dismissed the case, ruling that the evidence had been illegally obtained and at any rate the local authorities, not the governor, should handle law enforcement

The Mississippi Supreme Court later overruled the decision, but by that time liquor was flowing and dice were rolling. The governor bided his time.

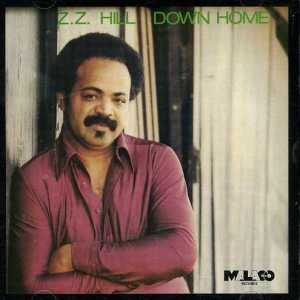

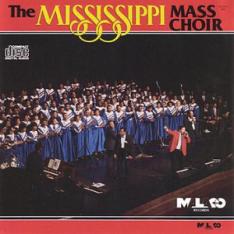

In the late 40s, a thriving black nightclub culture was in place. Places like the Blue Peacock, the Stamps Hotel (the only hotel in Mississippi that catered to Negros) with its famous Off-Beat Room, The Blue Flame, the Travelers Home and others, where national jazz and blues acts performed. These establishments ran advertisements in The Jackson Advocate, including one that offered a special bus from Farish and Hamilton.

By 1946, Rankin county was paying the highest black market tax in the state., but these high times came to a crashing end one hot day in August of 1946, when Seaney and Constable Norris Overby met at place called the Shady Rest and gunned each other down. Others had been killed, of course—often that big-ass catfish you hooked turned out to be someone you hadn’t seen in a while—but this double homicide so inflamed public opinion that illegal operations never dared be so blatant.

In the 50s, black businesses withered in the backlash against Brown vs. Board of Education, and the Gold Coast became dominated by a white gangster named “Big Red” Hydrick, who brought area as securely under his suzerainty as a corrupt satrap. Red’s little kingdom withered with urban sprawl.

Beale Street is back–sort of–and the French Quarter will–Dieu merci!–always be the French Quarter, but the Pearl’s Gold Coast is gone, lost in a little enclave under the interstate, a puzzle of gravel, asphalt, and weathered walls.